Executive summary

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) were established in 1974 to uphold the ethical foundations of human subjects research — respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Over time, however, many IRBs have drifted from this mandate. What began as a system for principled ethical oversight has morphed into a patchwork of local compliance offices that tend to prioritize procedure over meaningful ethical judgment.

The result is a landscape marked by inconsistent standards, unpredictable timelines, and unnecessary barriers to urgent scientific work. In our field research, we identified cases in which IRB processes delayed important research by more than a year (and in one case by 2.5 years) — not because of genuine ethical concerns, but due to bureaucratic inertia. Meanwhile, the real financial burden of IRB administration is obscured through indirect cost structures embedded in grant budgets, further insulating IRBs from accountability or performance pressure.

This inefficiency persists in part because academic investigators are often steered towards their own institution’s IRB and are effectively locked into a single-provider IRB model. With no option for recourse, they essentially become captive users.

Yet federal regulations do not require researchers to rely on their home institution’s IRB. Any federally compliant IRB — institutional or independent — may serve as the IRB of record if the institution signs a reliance agreement. This is already standard in multisite NIH studies, where use of a single central IRB has been mandatory since 2018, and in industry-sponsored trials, where academic sites routinely cede review to accredited independent IRBs. These boards compete on speed and service while meeting the same regulatory requirements as institutional IRBs.

Beyond efficiency, independent IRBs offer an important ethical advantage: structural separation from any single institution makes them less susceptible to conflicts of interest, internal politics, or undue influence by powerful investigators. An IRB that does not answer to the university’s leadership can render judgments free from pressures that have compromised institutional oversight in high-profile cases.

Specialization compounds these advantages. An institutional IRB may see a particular type of complex clinical trial once a year. An independent IRB reviewing hundreds of similar protocols develops familiarity with emerging issues, common pitfalls, and evolving best practices. This expertise translates into faster, more consistent review and potentially stronger protections for participants.

Academic investigators, however, rarely have the option to use external IRBs (which can be either institutional or independent). Internal university policies typically restrict them to their institution’s own IRB, preventing them from accessing the same independent boards that routinely review industry trials conducted at those very institutions. The result is a system where institutional IRBs face no pressure to improve, and research timelines suffer needlessly.

Granting academic investigators the freedom to choose among accredited IRBs would better align incentives across the IRB ecosystem, introducing competition, cost transparency, and accountability. This could be achieved with two policy shifts:

- Guaranteeing the right of federally funded investigators to select an external IRB as the IRB of record. This would be coupled with robust non-retaliation rules to protect researchers who choose an external IRB, and the elimination of duplicative internal review once an external IRB issues a determination. By allowing researchers to choose among compliant IRBs, and by making those options more visible, market discipline and accountability would be reintroduced into the oversight process.

- Prohibiting institutions from funding IRB operations through indirect costs. Decoupling IRBs from Facilities and Administrative costs will make prices more transparent, enabling researchers to make more informed choices, and encouraging competition in terms of speed, clarity, and rigor.

This proposal requires no new federal offices, certification regimes, or enforcement bodies. The federal system already recognizes reliance on external IRBs and provides a regulatory framework for their use through the Common Rule, Office for Human Research Protections guidance, and accreditation networks.

Evolution of institutional IRBs

IRBs were born out of concerns regarding serious ethical failures by researchers during the 20th century. Federal regulation of human subjects research began with the National Research Act of 1974, which was passed in the wake of ethically egregious medical experimentation projects such as the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.1 The National Research Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects, which led to the codification of research ethics principles in the Belmont Report, published in 1979. The report outlined the principles of ethical human research, emphasizing respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. These principles informed the core set of regulations governing human research codified by 45 CFR 46, also known as the “Common Rule.” In 1991, 15 federal agencies adopted the Common Rule.

For the first time, federally funded human subjects research across government agencies followed a unified ethical standard. During this period, IRBs were broadly tasked with evaluating studies for their risk-benefit balance and ensuring informed consent, while also providing additional protections for vulnerable populations, such as pregnant women and children.

In parallel with federal funding agencies, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also implemented its own regulations to ensure that privately funded research conducted for subsequent clinical purposes would be carried out in an ethical manner. In 1981, it adopted 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56, which require IRB review and informed consent for all clinical investigations involving FDA-regulated products, including drugs, biologics, and devices — regardless of funding source. Even privately funded industry trials have to comply with human subjects protections if they aim for FDA approval.

The early days of IRB oversight in academic institutions were characterized by a form of “collegial oversight,” that depended on unpaid faculty volunteers. This work was overseen by federal offices with limited authority and resources: chiefly, the Office for Protection from Research Risks (OPRR). Within the FDA, the responsibility for overseeing IRBs was divided across several offices, none of which was specifically dedicated to the issue. Overall, the IRB review process was largely left to its own devices, with subjective interpretation of complex regulations.

In the late 1990s, however, IRBs changed dramatically after a series of high-profile research scandals. In 1996, for example, a University of Rochester study resulted in the death of participant Nicole Wan, who was accidentally administered a lethal dose of lidocaine during a bronchoscopy procedure. In 1999, the Jesse Gelsinger case drew widespread attention after investigators found that he had not been fully informed of the known risks associated with the experimental gene therapy he received.

The publicity around these cases generated significant backlash and led to a so-called “federal show of force.” OPRR, which became the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP), began to curtail funding: between 1998 and 2002, HHS suspended or restricted federally funded research at eight major hospitals and universities after finding a failure to comply with proper IRB practices. This included renowned biomedical centers such as Duke University in 1999 and Johns Hopkins University in 2001. In 2000, The Chronicle of Higher Education noted that university administrators and researchers were fearful that their funding could be withdrawn, with “millions of dollars of research funds from the National Institutes of Health and pharmaceutical companies at stake.”

This fear has greatly shaped the current form of the IRB system. Federal inspections of IRBs in the late 1990s and early 2000s focused in large part not on substantive ethical failings, but on minute procedural deviations, for example, whether every step of ethical review was properly documented. In response, universities began hiring full-time IRB staff and compliance specialists to manage documentation and ensure bureaucratic conformity, which led to a “professionalization” of IRBs.

Professor Sarah Babb, a sociologist of human regulatory practices, argues in her book Regulating Human Research that review boards have deviated from their core task of safeguarding human participants as a result. Instead, institutional IRBs have increasingly started to function as a way for institutions to avoid noncompliance penalties, particularly withdrawal of funding. Pressure from both above, through federal agencies and regulatory requirements, and below, through institutional incentives and internal priorities, has caused IRBs to develop new characteristics:

- Proceduralism: ethical deliberation is gradually displaced by the demand for rigid documentation and standardized workflows, such that the process becomes more important than the judgment it was meant to support.

- Opacity: IRB decisions are increasingly insulated from scrutiny, lacking transparent reasoning, accessible justification, or meaningful avenues for review or appeal, creating an authority that operates without accountability.

- Administrative expansion: compliance offices grow in size and influence, as IRB staff evolve from part-time faculty advisors into full-time bureaucrats whose professional incentives favor risk aversion, rule proliferation, and institutional control.

These characteristics continue to define the IRB system that researchers navigate today. In some areas, the current IRB practices may cause more harm than good by delaying valuable research. Some bioethicists have argued that while stories like that of Jesse Gelsinger have captured the public’s attention, the hidden cost to delays introduced by ever-stricter IRBs means life-saving interventions reach some patients too late. This creates an “invisible graveyard” of patients who never benefit from therapies that could have saved them. The cost of delayed innovation due to slow IRB reviews is impossible to assess precisely, but even lower-bound estimates are sobering. For example, one methodology estimates that the delays to the ISIS-2 trial, a landmark randomized clinical trial published in 1988 that tested treatments for acute myocardial infarction, caused several thousand deaths.

This historical context matters for reform. The current balance of power and process is not the inevitable consequence of ethical principles, but rather the path-dependent outcome of past crises and the rational responses of institutions to funding conditions. Policy can recalibrate incentives without weakening ethical protections by giving investigators the choice to seek review from IRBs that are structurally independent of their home institution.

Why IRBs need reform

IRBs face strong incentives to avoid regulatory sanctions and weaker incentives to facilitate valuable research quickly. All research institutions conducting federally funded human subjects research must maintain an IRB or rely on an external one, and all IRBs must operate in compliance with federal policies enforced through audits by the OHRP. This commitment is documented through a Federalwide Assurance (FWA), a formal agreement with HHS that pledges compliance with the Common Rule and identifies the IRB responsible for oversight.

Most prominent medical journals require IRB approval, and studies conducted at federally funded hospitals must undergo IRB review even if the study itself isn’t federally funded. Nearly all medical research is dependent on IRBs.

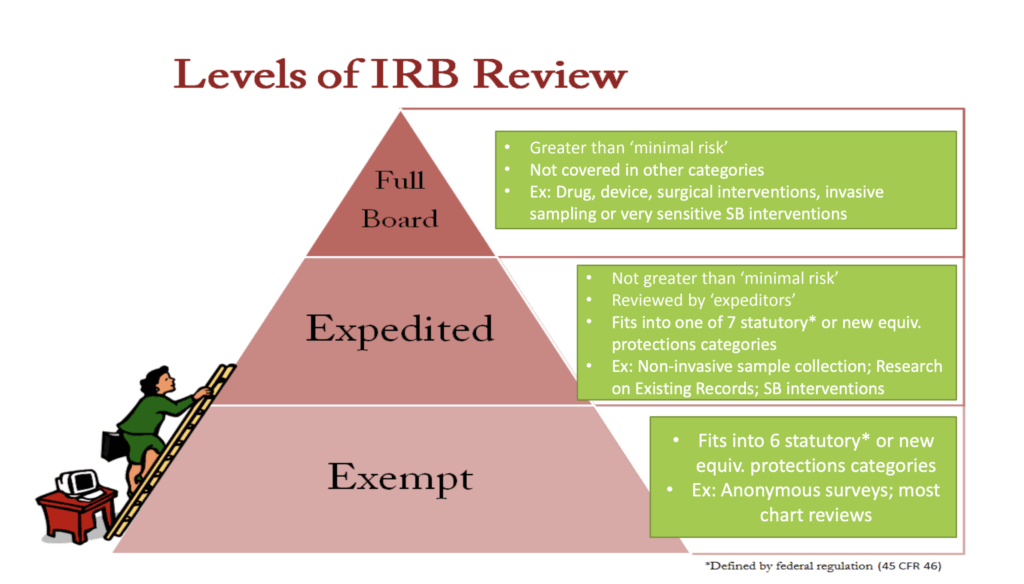

IRBs review human subjects research at three different levels depending on the level of risk:

- Exempt review applies to studies that involve minimal risk and fall into specific regulatory categories, requiring only administrative review. Examples include research involving anonymous or de-identified surveys, interviews, or educational tests or secondary analysis of existing data or biospecimens when the information is publicly available or recorded without identifiers.

- Expedited review is used for studies that pose no more than minimal risk to participants. Examples of eligible procedures include noninvasive data collection, such as surveys, interviews, or audio and video recordings; collection of biological specimens through routine or noninvasive methods, such as blood draws within approved volume limits, saliva, or cheek swabs.

- Full board review is required for studies that involve more than minimal risk, include vulnerable populations, or raise complex ethical concerns, and these must be evaluated by the entire IRB in a convened meeting. Interventional clinical trials always require full board review.

The classification of a study as exempt, expedited, or full board significantly influences the timeline for IRB approval, with full board review being the most lengthy.

The existing evidence suggests that many academic IRBs have drifted from their original mission. Surveys of researchers reveal that while they support the core ethical principles, they find IRB processes arbitrary, restrictive, and often counterproductive. Many believe the current system stifles productivity, adds costs without improving participant protections, and imposes delays over minor details. Deliberations occur behind closed doors, with no formal appeals process, often leaving investigators uncertain and frustrated.

These concerns are supported by systematic evidence. The largest meta-analysis in the field consists of a review of 52 primary studies on IRBs, and finds wide variation in efficiency, review time, and substantive judgments, even when reviewing identical protocols. Inconsistencies are driven by divergent local practices and interpretations rather than differences in risk or study design.

Overall, the available data suggest that existing IRB practices impose substantial and uneven burdens without clear corresponding gains in participant protection. The findings point to a system characterized by opacity, inconsistency, and unmeasured effectiveness. This underscores the need for regulatory reform to better align ethical review with both participant welfare and the efficient conduct of research.

These problems have long been acknowledged in official policy sources. In 2011, HHS explicitly called for “reducing burden, delay and ambiguity for investigators,” and recognized that “some IRBs have a tendency to overestimate the magnitude and probability of reasonably foreseeable risks.” A 2014 NIH Request for Comments on Draft Policy similarly noted that multi-site review “involves significant administrative burden in terms of IRB staff and members’ time to perform duplicative reviews.” These assessments were repeatedly offered in the context of calls for regulatory reform. Nevertheless, despite longstanding recognition of these problems, most efforts to meaningfully improve the IRB process have had limited success.

Ceding review to external IRBs: NIH’s single IRB mandate and industry trials

A notable exception to the failure of most IRB reforms is the NIH’s single IRB (sIRB) mandate for all NIH-funded multisite studies involving human participants, which was adopted in 2018. The policy requires all participating sites in a multisite NIH-funded trial to cede review to a central IRB, eliminating duplicative institutional reviews that added delays without improving ethical rigor. The explicit goal of the sIRB mandate was “to enhance and streamline the IRB review process in the context of multi-site research so that research can proceed as effectively and expeditiously as possible.” However, because most medical research is not NIH-funded, the benefits of the sIRB mandate currently apply only to a subset of studies.

The sIRB policy demonstrates that ceding review authority to an external IRB is both feasible and compatible with federally funded research. Now fully implemented, it mandates that even the largest academic medical centers adapt their compliance systems to accept IRB oversight from outside institutions. To help ease ceding review, the Streamlined, Multisite, Accelerated Resources for Trials (SMART) IRB Reliance platform helped develop standardized agreements with support from the NIH. This facilitates single IRB review for multisite studies by providing master reliance agreements, common operating procedures, and an online system that enables institutions to document and manage reliance relationships without study-specific legal negotiation. Early experience indicates that this transition has been successful and the outcomes positive.

The NIH-funded INVESTED trial, which compared two influenza vaccine formulations in high-risk cardiovascular patients, piloted the use of the sIRB model through the SMART IRB Reliance platform. All participating institutions, apart from the central one, ceded ethical review to a central IRB, resulting in significantly faster study initiation. On average, ceded sites achieved IRB approval 33% faster (81 versus 121 days). Despite these efficiency gains, ceded sites reported higher initial costs and increased administrative workload due to unfamiliarity with the new process.

Overall, the study demonstrated the potential of centralized IRB review to streamline multisite trials while also highlighting the need for institutional culture change. For example, the study reports that while some sites formally agreed to ceding IRB review to the central IRB, they still performed parts of their own local IRB review anyway. This behavior undermines the purpose of using a single IRB, which is to eliminate redundant reviews and reduce delays.

Independent versus institutional IRBs: timelines and cost

Independent IRBs are ethics review boards that operate outside any single hospital or university. Researchers engage an independent IRB on a fee-for-service basis to review and monitor their research involving human participants. This model has become widely used by industry sponsors even when conducting trials at academic centers, because it provides faster and more predictable turnaround times while still maintaining regulatory compliance. Consequently, usage of independent IRBs has grown markedly, rising from 25% of investigational drug research in 2012 to 48% in 2021.

BRANY is a clear example of this model. It was founded in 1998 by four major New York-area academic medical centers: NYU School of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System.2 They created BRANY because, individually, their institutional review boards and research-management infrastructures were often too slow, duplicative, and costly, which made it increasingly hard to attract and run industry-sponsored clinical trials in a competitive environment.

Independent IRBs are federally regulated and can seek accreditation. In 2001, the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs (AAHRPP) established a voluntary accreditation program that evaluates an organization’s entire Human Research Protection Program (HRPP). AAHRPP accreditation goes beyond minimal compliance to ensure an institution has a well-functioning, organization-wide system for protecting research participants. AAHRPP accreditation has become a quality signal in the market, and sponsors increasingly require it. The most widely used independent IRBs hold AAHRPP’s highest level of accreditation and now review a substantial proportion of industry-sponsored clinical trials

Independent IRBs offer two distinct advantages from a research participant protection perspective. First, their scale enables greater efficiency and consistency. Reviewing thousands of protocols each year, often including complex, multisite, or high-risk trials, develops expertise on emerging ethical issues that only comes with volume. Second, they may provide stronger ethical oversight because their structural separation from any single institution insulates them from institutional conflicts of interest.

Institutional IRBs are embedded within organizations that employ investigators, depend on grant revenue, and are influenced by senior faculty and leadership, which can distort ethical review when protocols are led by influential or well-funded investigators.

The death of Jesse Gelsinger illustrates how individual and institutional conflicts of interest can undermine ethical oversight. The principal investigator, Dr. James Wilson, held significant financial interests in a biotechnology company that stood to benefit from the trial, while simultaneously directing a major research institute at the host university. At the same time, the university waived portions of its conflict-of-interest policies, granted exclusive licensing rights to the company, and depended on it for substantial research funding. Oversight bodies were largely composed of internal faculty, raising concerns about the independence of ethical review.

Subsequent investigations revealed ongoing protocol deviations and failures in adverse-event reporting that went uncorrected, suggesting that institutional IRBs may struggle to act as independent ethical counterweights when powerful investigators and institutional financial interests are in play.

To inform ongoing discussions about IRB reform — particularly whether increased competition and cost transparency might benefit the research ecosystem — we conducted a structured comparison of the two factors most relevant to study activation: review timelines and costs. Specifically, we compared the performance of independent IRBs with that of institutional IRBs across both dimensions.

For timelines, we drew on published literature examining institutional IRB performance and published timelines of three independent IRBs: WCG, Advarra, and BRANY.3 To validate and contextualize these findings, we also conducted informal interviews with stakeholders at universities and independent IRBs, including investigators who interface with both institutional and commercial review boards, as well as representatives from independent IRBs.There are relatively few studies that directly assess institutional IRB timelines quantitatively. An exception is a study on IRB timelines from a Veterans Affairs Medical Center carried out between 2009 and 2011. Based on informal conversations with academics, these timelines are representative of institutional IRBs more broadly. We compared the data from this study with timelines of the independent IRB BRANY. These timelines have been broken down by study category.

Beyond the overall speed advantage of private IRBs, the most striking feature of this comparison is the large variability in review time — even within the same medical center. Interviews with biomedical researchers confirmed this variability. Differences emerged not only within institutions but also between them. Academics at some institutions described fast, constructive review processes, while others reported severe delays that bore little relationship to the risk profile or scientific complexity of their studies.

One particularly telling case involved a rare-disease study using only existing biobank samples — a category normally eligible for exempt or expedited review. Approval took a total of 2.5 years. The delay stemmed not from substantive ethical concerns but rather from bureaucratic hurdles. To begin with, investigators were discouraged from writing their own application and were instead required to go through an “IRB writer” employed by the university. Six months passed before a first draft was created, after which the application entered a cycle of contradictory edits and shifting requirements, all routed back through the same bottlenecked writer. A process that should have been routine became an ordeal that materially hindered research.

To understand how this could have been handled by another IRB, we later described the anonymized protocol to an AAHRPP-accredited independent IRB. They indicated it would almost certainly have qualified for exempt status — with a one-time fee of $1,105 and an estimated turnaround time of roughly seven days. When informed of the price, the investigator noted that they would have happily paid more than that to avoid years of delay.

Across interviews, two cross-cutting themes emerged. First, most researchers would only criticize their institutional IRB anonymously, fearing retaliation that might affect funding, access to resources, or career trajectories. Second, many did not realize independent IRBs were even an option, a sign of how thoroughly institutions control the ethical approval process.

Cost comparisons were more complex. The internal fees of institutional IRBs cannot be measured directly for federally funded studies because IRB costs are wrapped into institutions’ indirect “Facilities and Administrative” (F&A) rates. These charges are pooled, making it impossible for investigators to know what proportion of the grant dollars that are allocated to indirect costs support IRB operations. However, many universities charge industry sponsors directly for IRB review, and those fee schedules are often publicly posted. We therefore compared full board and expedited review fees from 44 R1 institutional IRBs that have publicly available fee information with the fee schedules of the three aforementioned independent IRBs (BRANY, WCG, and Advarra).4

These comparisons challenge assumptions, revealing that independent IRBs charge similar fees to industry sponsors as institutional IRBs do. Unlike most institutional IRBs, independent IRBs had a flat fee structure across initial and continuing review, as well as exempt and full board. Continuing fees were uniformly higher for independent IRBs, suggesting a widening gap with length of study duration. However, when considered in the context of a typical R01-equivalent grant (average of $664,000 annual total costs in 2025),5 the absolute cost of independent IRB review is relatively modest.

Taken together, the existing evidence demonstrates that institutional IRB review times can vary sharply even within the same institution. Earlier policy changes were motivated by a legitimate desire to protect human subjects, but the system now wastes researcher time and taxpayer dollars, delays important discoveries, and costs human lives. Independent IRBs already operate under the same federal regulatory requirements — and in many cases, higher quality and accreditation standards — while offering faster and more consistent review, with similar pricing structures to what universities charge industry sponsors.

The evidence shows that independent IRBs could offer faster, more consistent review under the same regulatory framework. Yet researchers are routinely denied access to them under the current regulatory regime.

Policy proposals to ensure investigator choice

Given the widespread use of independent IRBs by commercial sponsors, the existence of robust oversight and accreditation frameworks, and the NIH single-IRB precedent, academic researchers should be permitted to rely on any registered IRB. We propose the following policies to eliminate procedural and financial frictions that currently undermine investigator choice of IRBs. By making options visible, accessible, and institutionally supported, investigator choice could incentivize better performance, shorten review times, and increase accountability.

Reduce frictions to relying on independent IRBs

Investigators should be guaranteed meaningful freedom to select an institutional review board of record for federally funded human-subjects research. Institutions that receive federal research funding must be required to permit investigators to designate a qualified external IRB without discretionary institutional approval. Where an external IRB is properly constituted under 45 CFR part 46 and, where applicable, 21 CFR Parts 50 and 56, and maintains an active registration with the OHRP, the investigator’s home institution must cede ethical review authority to that IRB, subject to the institution’s pre-selected reliance elections. Reliance in such cases should be automatic and non-discretionary. At the same time, investigators should retain the option to use their home institution’s IRB when they believe it offers superior substantive review or contextual expertise.

To rely on an external IRB, institutions must enter into a reliance agreement — a formal arrangement ceding IRB review authority. Yet even with shared frameworks like SMART IRB, experience under the NIH single-IRB policy shows that infrastructure alone is insufficient. In practice, institutions often obstruct reliance through duplicative review and administrative delay. This experience suggests that meaningful reform must make investigator choice operative in practice, not just permissible in theory. The solution is to bind institutional discretion to narrow circumstances, defaulting to investigator choice. Informed by existing reports around the barriers to the implementation of the single-IRB NIH policy, we recommend the following measures:

- The FWA should embed an enforceable obligation to accept reliance when an investigator designates a qualified reviewing IRB. This shifts reliance from an ad hoc negotiation to an ex ante requirement of an institution’s Federalwide Assurance. With this modified form of the FWA, institutions would pre-commit to rely on investigator-designated, compliant IRBs, which would eliminate the need for case-by-case institutional permission.

- OHRP should standardize reliance statements and local context forms. Informed by the SMART IRB national reliance platform, OHRP should create a reliance agreement template: a pre-negotiated, standardized text with a constrained menu of OHRP-defined elections that an institution automatically adopts when it submits an FWA. SMART created master reliance agreements to eliminate the months of legal negotiation that stalled reliance decisions by defining the responsibilities of reviewing IRBs and relying institutions in advance. Here, the reliance agreement would be mandatory, universal, and legally embedded in the FWA, preventing institutions from imposing supplemental procedural hurdles, tactics widely used to resist reliance during implementation of the NIH single-IRB policy. OHRP should create the agreement in consultation with institutions, and allow for limited elections, such as the country of external IRB, accreditation status, or whether external IRBs can review research subject to additional protections in the Common Rule.

Alongside master reliance agreements, HHS should require standardized local context forms, limited to information such as applicable state laws, institutional policies, and required ancillary approvals (e.g., biosafety or radiation safety). While local context is necessary, studies show institutions often expand it into a second ethical review or parallel oversight process, undermining reliance. When local context forms are unstandardized, institutions can add requirements that become a tool for delay or a pretext for re-reviewing ethical judgments that should belong to the IRB of record. Standardization and strict scope limits would prevent “local context creep” from becoming a tool for delay or obstruction. - HHS should maintain a publicly accessible registry of federally compliant IRBs with accreditations and other quality metrics. Expanding on the current database, the registry should include federally recognized accreditation statuses, alongside contact information and, for institutions, FWA documentation such as reliance terms. Public visibility into compliant IRBs and an institution’s scope of reliance supports informed IRB choice. To inform investigators, HHS should conduct direct outreach, clarifying an investigator’s right to select a qualified external IRB. Institutions should be required to inform investigators of this right at the protocol planning stage. The registry would provide investigators with an up-to-date resource on an IRB’s regulatory compliance and accreditation status, which can signal reviewer expertise, consistency of decisions, and quality-assurance systems to investigators.

- HHS should establish a secure, anonymous reporting channel for investigators and institutions. In addition to reporting incidents, OHRP should create a reporting mechanism to investigate cases where institutions retaliate against or disadvantage investigators who select a federally compliant external IRB, or cases where institutions believe an external IRB is out of compliance. The reported violations should trigger an investigation and potential reassessment of the institution’s status. To effectively investigate IRBs in a timely manner, HHS should sufficiently staff OHRP’s compliance office and increase random routine inspections.

- Ensure high-quality ethical review by strengthening oversight of IRBs. High-quality ethical review can be strengthened by increasing oversight of IRBs and requiring AAHRPP accreditation. HHS should implement routine, risk-based spot checks of IRBs to ensure consistent adherence to ethical and regulatory standards. To enforce higher standards than required by regulation, agencies could limit eligibility for reliance to accredited IRBs to further promote accountability, standardization, and high ethical performance.

Under this framework, a researcher could select any IRB in the OHRP database that meets their institution’s reliance criteria and proceed with IRB review. Because the master reliance agreement is embedded in the FWA and not subject to local modification, institutions would have no authority to refuse reliance or impose additional contractual terms. Local context forms would be the sole mechanism for conveying institution-specific requirements. This ensures reliance remains an administrative step rather than a discretionary gatekeeping process.

Under reliance agreements, ethical responsibility and liability should remain clearly delineated. Ethical responsibility should follow the IRB of record, consistent with current Common Rule principles. The reviewing IRB would bear responsibility for ethical determinations and regulatory compliance, and OHRP oversight would appropriately focus on an IRB’s performance. Relying institutions would not be held accountable for ethical decisions they did not make, reducing institutional incentives to re-review protocols defensively or impose duplicative oversight to manage perceived liability risk. Relying institutions would retain responsibility for investigator oversight, compliance with state and local law, ancillary safety approvals, and ensuring accordance with the approved protocol.

The end goal of these reforms is to create a system in which investigator-designated IRB review is automatic, ethical responsibility clearly follows the IRB of record, and institutional gatekeeping is eliminated without weakening human-subjects protections.

Make IRB financing transparent to investigators

Current IRB financing hides the true costs and distorts incentives. At most research institutions, IRBs are funded through pooled F&A costs, so investigators never see what IRB review actually costs in dollar terms. Without a price signal, researchers cannot compare IRBs, and institutional IRB review appears free despite consuming real resources and imposing meaningful costs on research timelines.

The largest costs that IRBs impose on researchers come from delay: stalled studies, missed enrollment windows, disrupted staffing, and slower generation of results. Yet because IRBs are insulated by F&A funding, slow or inconsistent review does not register anywhere in a way that affects an IRB’s budget or incentives. The costs are borne instead by investigators and sponsors, who absorb the consequences of delay without any mechanism to signal that time, expertise, or responsiveness matter. This insulation weakens accountability and makes it difficult for institutions to improve IRB performance in ways that align with the needs of active research programs.

The current financing structure also contributes to locking researchers into using their institutional IRB. Because institutional IRB costs are hidden in overhead while external IRBs are often paid for through direct costs, investigators face a financially punitive choice even when an external IRB would be faster, more experienced with a given protocol type, or cheaper. The appearance of a ‘free’ institutional IRB is a subsidy created by institutional policies.

Requiring IRB review to be treated as a direct, budgetable research cost could address these distortions. Investigators should include IRB review as an explicit line item in direct costs and choose whether to spend those funds on an institutional or accredited external IRB, without double-paying through F&A.

Conclusion

IRBs exist to protect human participants, not to entrench bureaucratic processes. Yet the current system too often rewards procedural risk aversion over timely, substantive ethical judgment, delaying valuable research without demonstrable gains in participant safety.

The reforms proposed here would realign ethical oversight with scientific progress and the public interest. Guaranteeing investigators the right to choose among federally compliant, properly accredited IRBs would introduce competition, accountability, and transparency into a system currently characterized by opacity and institutional monopolies. Independent and external IRBs, free from local institutional pressures, reduce conflicts of interest and benefit from reviewing a higher volume of studies, enabling greater specialization and more consistent ethical evaluation.

Embedding automatic reliance into Federalwide Assurances and standardizing reliance agreements would eliminate duplicative review and discretionary institutional gatekeeping, while clearly assigning ethical responsibility to a single IRB of record.

Making IRB costs transparent and budgetable would further realign incentives by exposing the true cost of delay and ending the hidden subsidies that lock investigators into slow or inconsistent review processes. Unlike previous proposals of IRB reform, these policy changes require no new bureaucracy.

Allowing investigator choice would ensure that IRBs once again fulfill their core mission: protecting human subjects while enabling socially valuable research to proceed without unnecessary delay.

Appendix

Questions and answers

1. Why not reform institutional IRBs?

Alternative IRB reform proposals, such as new reporting requirements or more audits, appear attractive but are less practical than the solutions we propose. Implementing themwould require a level of federal monitoring and enforcement capacity that does not exist. As scholars like Sarah Babb and Carl Schneider have shown, IRBs function as self-reinforcing local “administocracies,” sustained by institutional autonomy, bureaucratic inertia and resistance to top-down harmonization. Mandating uniform oversight would require building extensive new infrastructure and enforcing compliance across thousands of institutions. Such an undertaking lacks both resources and political will. The current system exists because the government delegated responsibility to local bodies. Expecting these institutions to enforce reforms that would limit their own discretion is unrealistic. By contrast, allowing researchers to choose among qualified independent IRBs introduces competition and accountability without requiring a major expansion of state capacity.

2. Won’t competition incentivize IRBs to lower standards to attract business?

Independent IRBs operate under regulatory, legal, and reputational constraints that make low-quality review a losing strategy. All IRBs are subject to the same federal requirements under the Common Rule and FDA regulations, and failed audits by OHRP or the FDA jeopardize an IRB’s ability to operate. Furthermore, independent IRBs already review a large proportion of trials with industry sponsors.

There is no evidence that institutional IRBs are ethically superior. In fact, the opposite might be the case. First, the scale of independent IRBs enables greater consistency and specialization. Reviewing thousands of protocols each year, often including complex, multisite, or high-risk trials, develops expertise on emerging ethical issues that only comes with volume. Second, they may provide stronger ethical oversight because their structural separation from any single institution insulates them from institutional conflicts of interest.

Ethical quality can be further safeguarded by strengthening oversight. HHS should conduct routine, risk-based spot checks of IRBs, focusing on the small number of independent boards that review a large share of protocols. Limiting eligibility to AAHRPP-accredited IRBs would further ensure high ethical performance. With these safeguards in place, competition could raise standards rather than erode them.

3. How will legal liability be adjudicated?

Institutions often cite legal liability as a reason to resist ceding IRB review. This concern is already addressed under existing multisite IRB reliance frameworks, including the NIH single-IRB mandate and the SMART IRB master reliance agreement, which clearly delineate responsibilities between reviewing IRBs and relying institutions. Reviewing IRBs assume responsibility for ethical and regulatory determinations, including risk-benefit assessment, informed consent, continuing review, and required reporting to federal regulators, while relying institutions retain responsibility for investigator oversight, compliance with state and local law, ancillary safety approvals, and ensuring accordance with the approved protocol.

In practice, legal liability in human subjects research almost always arises from failures in execution — deficient consent processes, protocol deviations, inadequate monitoring, or clinical negligence — which remain under institutional and investigator control. As legal scholars note, IRBs lack visibility into real-time research conduct and therefore cannot function as the primary legal safeguard for participant protection.

The belief that local IRBs meaningfully reduce legal liability is best understood historically: following OPRR/OHRP enforcement actions in the 1990s and early 2000s, institutions used stricter IRB processes to protect specifically against regulatory sanctions and withdrawal of funding, not tort liability. This led IRBs to emphasize procedural compliance and documentation — practices that mitigate regulatory risk but do little to enhance participant safety or reduce legal exposure. Over time, however, protections against regulatory enforcement and protections against legal liability became conflated, obscuring the distinct and limited role IRBs actually play in managing legal risk.

4. How will local context be considered?

Federal regulations appropriately recognize that certain site-specific factors must be conveyed to a reviewing IRB, including: applicable state and local laws governing consent, privacy, or mandatory reporting; institutional requirements for investigator eligibility, site-specific resources, populations, or standards of care; and required ancillary approvals such as biosafety, radiation safety, or conflict-of-interest review.

In practice, however, experience with the NIH single-IRB (sIRB) mandate shows that institutions often expand “local context” beyond these legitimate domains, using it to conduct parallel ethical review, impose additional conditions, or delay reliance.

A reformed system should therefore rest on two core principles: strict scope limits and standardization. Local context forms must be confined to objective, site-specific information that a reviewing IRB cannot reasonably know on its own, while all ethical judgments regarding risk-benefit balance, consent adequacy, and subject selection remain exclusively with the reviewing IRB. To enforce this boundary, HHS should mandate a uniform local-context form for each institution to be submitted annually that cannot be renegotiated.

5. Can an institution block a study that they deem inappropriate?

Institutions retain the authority to decline participation in a study, but not on the basis of ethical determinations that fall within the jurisdiction of the IRB of record. Under the proposed framework, ethical review — including risk-benefit assessment, informed consent, subject selection, and continuing review — is exclusively the responsibility of the reviewing IRB. Allowing relying institutions to block studies on ethical grounds would reintroduce duplicative review and discretionary gatekeeping that reliance is intended to eliminate.

Institutions may decline to host a study only on narrowly defined, non-ethical grounds, such as lack of required facilities or personnel, conflicts with applicable law, investigator ineligibility, failure to obtain required ancillary approvals, or unrelated contractual or resource constraints. These decisions reflect institutional capacity and legal compliance rather than ethical review.

If an institution believes a reviewing IRB has approved a study that is ethically improper or noncompliant, the appropriate remedy should be escalation to federal oversight authorities. During the time such a complaint is being judged, the study will be paused. Institutions may submit formal complaints to OHRP or, where applicable, the FDA, which have authority to investigate IRBs, require corrective action, suspend registrations, or restrict an IRB’s ability to serve as an IRB of record. This reporting mechanism serves as a backstop for IRB malpractice or systematic failure, preserving ethical rigor while preventing institutions from using speculative liability concerns to obstruct reliance.

Details on regulatory changes and implementation

1. Implementation

Reliance on an external IRB should be automatic by default and subject only to narrow objections tied to an institution’s responsibility for research conduct, not ethical judgment. Permissible objections should be limited to investigator eligibility and training (e.g., lack of required human-subjects training, or clinical credentialing); missing or denied ancillary approvals necessary for study conduct (such as biosafety, radiation safety, pharmacy, laboratory, or data-security review); unmanaged institutional conflicts of interest involving the investigator or institution; and lack of operational feasibility, where the site lacks the personnel, infrastructure, or resources to safely implement the study. These objections reflect legitimate institutional control over who may conduct research and whether it can be operationalized at a given site, while excluding ethical determinations, which remain the exclusive responsibility of the reviewing IRB.

We recommend that institutions operationalize external IRB reliance through the current Federalwide Assurance system. This can be modeled after the SMART IRB portal or widely-used reliance agreements. The system shall maintain a continuously updated registry of externally reviewed studies to support oversight, auditing, and compliance activities.

2. Regulatory changes

We also recommend targeted regulatory changes by adding the following bolded text to the Common Rule.

§46.103(e) For nonexempt research involving human subjects covered by this policy (or exempt research for which limited IRB review takes place pursuant to § 46.104(d)(2)(iii), (d)(3)(i)(C), or (d)(7) or (8)) that takes place at an institution in which IRB oversight is conducted by an IRB that is not operated by the institution, the institution shall rely on the IRB for oversight of the research and shall allocate responsibilities in accordance with the reliance agreements and directives designated by the institution in its approved assurance, where applicable. Only where the IRB does not meet the conditions for reliance specified in the institution’s assurance, the institution and the organization operating the IRB shall document the institution’s reliance on the IRB for oversight of the research and the responsibilities that each entity will undertake to ensure compliance with the requirements of this policy (e.g., in a written agreement between the institution and the IRB, by implementation of an institution-wide policy directive providing the allocation of responsibilities between the institution and an IRB that is not affiliated with the institution, or as set forth in a research protocol).

§46.103(f) As a condition of an approved assurance, an institution shall permit an investigator conducting research covered by this policy to designate a registered IRB that meets reliance criteria specified in the institution’s assurance required by this part, and shall rely on that IRB for such review unless reliance would violate applicable laws. Conflicting institutional policy alone shall not be a sufficient basis to refuse reliance.

§ 46.112 Review by institution. Research covered by this policy that has been approved by an IRB may be subject to further appropriate review and approval or disapproval by officials of the institution. However, those officials may not approve the research if it has not been approved by an IRB. Such institutional review shall not include independent or duplicative review by a separate IRB where the research has been approved by an IRB upon which the institution relies in accordance with this part.

§46.114(c) For research not subject to paragraph (b) of this section, an institution participating in a cooperative project may enter into a joint review arrangement, rely on the review of another IRB, or make similar arrangements for avoiding duplication of effort. Where reliance is provided for under the institution’s assurance, the institution shall not require additional IRB review.

To change the default to IRB reliance, we recommend changing Section 6 of Federalwide Assurance (FWA) for the Protection of Human Subjects to read:

6. Reliance on an External IRB

Whenever the Institution relies upon an IRB operated by another institution or organization for review of research to which the FWA applies, the Institution must ensure that this arrangement is documented by a written agreement between the Institution and the other institution or organization operating the IRB that outlines their relationship such reliance shall be governed by the reliance commitments and eligibility criteria specified in the Institution’s approved Federalwide Assurance (FWA).

The Institution’s FWA shall identify the categories of external IRBs upon which the Institution agrees to rely, and the conditions under which such reliance is automatic upon investigator designation following OHRP’s IRB Reliance Template. and includes a commitment that the IRB will adhere to the requirements of the Institution’s FWA.

OHRP’s sample IRB Authorization Agreement may be used for such purpose to document supplemental reliance arrangements not already provided for under the Institution’s FWA, or the parties involved may develop their own agreement consistent with the Institution’s assurance and applicable regulations.This agreement must be kept on file at both institutions/organizationsThe Institution’s approved FWA, including any incorporated reliance framework or master reliance agreement, shall be publicly available through OHRP’s registry of assurances and may be relied upon by investigators and external IRBs. Any supplemental reliance agreements shall be kept on file at both institutions/organizations and made available upon request to OHRP or any U.S. federal department or agency conducting or supporting research to which the FWA applies.

Fees for independent IRBs

Independent IRBs have a flat fee structure across initial and continuing review, as well as exempt and full board. The exact fees for the three IRBs we mention in this proposal are in the table below.

Additional resources

- David Hyman, Institutional Review Boards: Is this the least worst we can do?, 2006.

- Carl Schneider, The Censor’s Hand: The Misregulation of Human-Subject Research, 2015.

- Jonathan Green, Polly Goodman, Aaron Kirby, Nichelle Cobb and Barbara Bierer, Implementation of single IRB for multisite human subjects research: Persistent challenges and possible solutions, 2023.

- Sarah Babb, Regulating Human Research, 2020.

- George Silberman and Katherine Khan, Burdens on Research Imposed by Institutional Review Boards: The State of the Evidence and Its Implications for Regulatory Reform, 2011.

- Scott Alexander, My IRB nightmare, 2017.

-

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study investigated the progression of untreated syphilis from 1932 to 1972 in 600 African-American men, 399 with syphilis and 201 without. Researchers with the US Public Health Service misled the participants and did not provide standard treatments. Even after penicillin became the standard cure, researchers withheld it to study the disease’s progression. The study caused needless suffering and death, ultimately contributing to widespread public outrage and the creation of modern research ethics regulations.

-

Mount Sinai School of Medicine is now known as Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and North Shore-Long Island Jewish Health System is now part of Northwell Health.

-

WCG and Advarra were selected because they are the two largest independent IRBs, while BRANY was included because of its tight ties to academic centers.

-

The 44 R1 universities in this sample are Boston University, Columbia University in the City of New York, Duke University, Georgetown University, Howard University, Johns Hopkins University, Medical University of South Carolina, Northeastern University, Rutgers University – New Brunswick, Saint Louis University, Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, Stanford University, Stony Brook University, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Pennsylvania State University, Tulane University, University at Buffalo, University of Alabama, University of California, Davis, University of California, Irvine, University of California, Los Angeles, University of California, Riverside, University of California, San Diego, University of California, San Francisco, University of Cincinnati, University of Colorado Denver, University of Houston, University of Illinois Chicago, University of Iowa, University of Kansas Medical Center, University of Louisville, University of Michigan, University of Missouri, University of Pennsylvania, University of Pittsburgh, University of South Carolina – Columbia, University of South Florida, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, University of Tennessee–Knoxville (UTK) / UT Medical Center, University of Toledo, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), West Virginia University, and Yale University.

-

R01s fund well-defined research projects that are expected to advance scientific knowledge, typically in biomedical, behavioral, or health-related fields.