- Download PDF

-

- Introduction

- (v) Metascience research to improve federal grantmaking processes

- (vi) Reforms to pursue more high-risk, high-reward research

- (vii) Novel institutional models that complement university structures

- (viii) Advances in AI systems to transform scientific research

- (ix) Statutes, regulations, or policies that create barriers to scientific research

In November 2025, the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) issued a request for information on federal policy updates to accelerate the American scientific enterprise, enable groundbreaking discoveries, and ensure that scientific progress and technological innovation benefit all Americans. IFP submitted the following response.

Introduction

The White House Office of Science and Technology Policy requested input on ways to expand scientific knowledge and improve mechanisms to transition discoveries to the marketplace. Metascience evidence and institutional innovation can accelerate the pace and efficiency of science, bringing more benefits of innovation to Americans.

We focus our response on five areas:

- Metascience research to improve federal grantmaking processes (Question v)

- Reforms to pursue more high-risk, high-reward research (Question vi)

- Novel institutional models that complement university structures (Question vii)

- Advances in AI systems to transform scientific research (Question viii)

- Statutes, regulations, or policies that create barriers to scientific research (Question ix)

(v) Metascience research to improve federal grantmaking processes

Over the past two decades, metascience research has documented significant challenges and inefficiencies in federal grantmaking. This body of work broadly indicates both that federally funded basic research generates high returns on investment,1 that scientific progress has slowed,2 and that scientific advances have become costlier.

On the federal level, studies demonstrate that peer review committees behave with substantial caution, as reviewers penalize innovative ideas.3 Concurrently, the average age of NIH principal investigators increased from 39 to 514between 1980 and 2008, suggesting that we are missing out on the cutting-edge ideas of many early-career scientists. Beyond these structural issues, researchers report spending up to 44% of their time5 on grant writing and reporting and must wait months — sometimes years — for responses to federal grant applications. These burdens reduce productivity and slow scientific discovery.

Agencies can implement specific reforms in response to these findings. Additionally, we recommend that the federal government develop institutional structures to increase the speed and efficiency of science. Below we describe targeted reforms, and then propose agency-based metascience units as a systematic approach to improving federally funded science.

Targeted reforms

Often reforms can address multiple problems simultaneously. To incentivize higher-risk research and accelerate grantmaking, agencies can hire and empower6 talented program officers to make funding decisions, as DARPA, ARPA-E, and the National Science Foundation have done successfully. Funders have sometimes combined program officer-selected projects with “fast grants,” where the funder quickly solicits, selects, and funds projects.

These mechanisms accelerate the pace of science and have been effectively used by NSF when urgent research is needed (such as during COVID-19) or when ideas are at an early stage, but have a high potential for impact. Elsewhere, IFP has documented how NSF used fast grant mechanisms to respond to COVID-19 faster than the National Institutes of Health (NIH). In addition, agencies can pilot “golden tickets,”7 a promising approach that allows individual peer reviewers to advance a project for funding even when other reviewers disagree.

To lower barriers for early-career scientists, reduce paperwork burdens, and shorten time to award, agencies could expand the use of multi-stage review processes using brief concept notes or letters of intent. In this approach, program officers provide feedback on brief concept notes, filtering out lower-quality projects and empowering early-career researchers to submit ideas without preparing lengthy applications. A down-selected group then submits full applications for full peer review. As the National Academies suggested in Simplifying Research Regulations and Policies: Optimizing American Science, multi-stage review can speed up science funding while improving project quality.

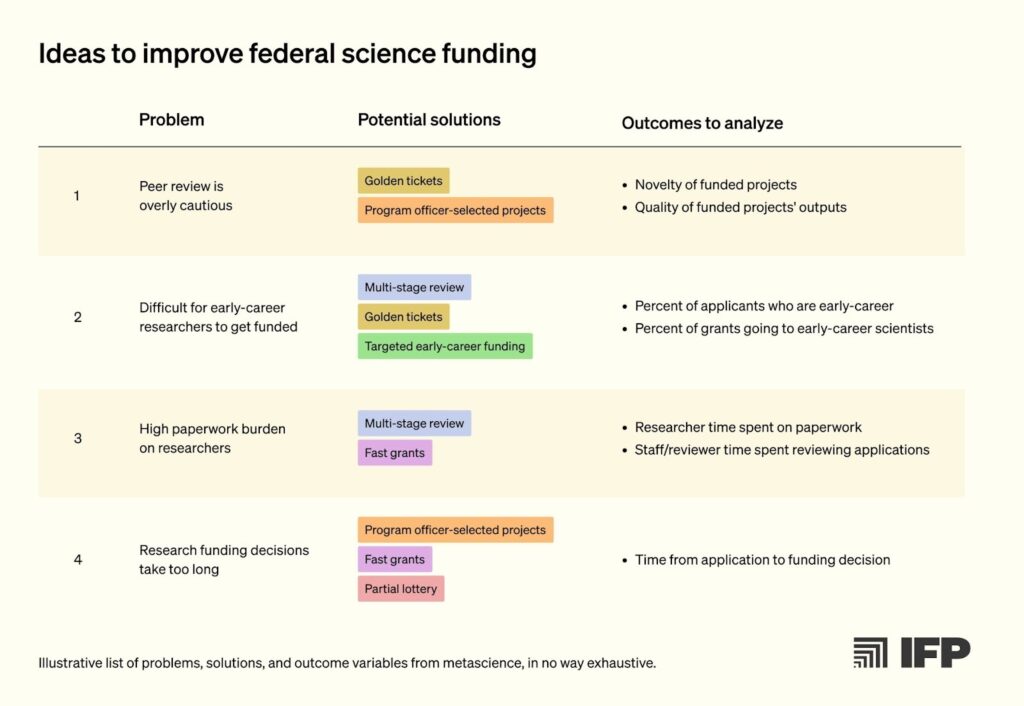

The table below provides a stylized view of four problems facing federal science funding, potential solutions, and how the effectiveness of these solutions might be evaluated.

Institutional innovation: Agency metascience units

While the approaches described above show promise, we have more evidence about the problems with American science than we do about effective solutions. As the largest funder of basic research in the US, the federal government is uniquely positioned to lead in experimenting with new funding models and evaluating their effectiveness.

One approach is to establish metascience offices within science agencies. These offices would provide dedicated expertise and focus on process improvement by metascience experts working with agency leadership. We recommend establishing metascience units within each major science funding agency: NSF, NIH, and Department of Energy (DOE).

These units should be housed in the agency leadership office, rather than embedded within a single directorate, office, or institute, to ensure cross-agency visibility and protect against capture by any particular program. Each unit should be staffed with 5–10 researchers with expertise in science of science, program evaluation, and data science, supplemented by rotating program officers who bring operational knowledge.

Metascience units should be empowered to run randomized experiments and retrospective analyses focused on genuine process improvement rather than compliance reporting. For example, a metascience unit at NIH could randomize whether study sections use golden tickets, then track the novelty and impact of funded projects across conditions. At NSF, a unit might compare outcomes from fast grants versus standard review timelines within a directorate. These units would need access to application data, review scores, and bibliometric outcomes, requiring data-sharing protocols with appropriate privacy protections.

Critically, metascience units should have authority to mandate pilots across agency programs, not merely an advisory role. Their findings should be published externally to build the broader evidence base on what works in science funding. In 2024, the United Kingdom established a Metascience Unit within UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). The Metascience Unit funds grants to grow the UK’s metascience community, conducts internal experiments on what works in science funding, and disseminates metascience insights across the UK’s R&D ecosystem. In the short time it has existed, the UK Metascience Unit has produced evidence on distributed peer review (where research applicants review each other), partial randomization of awards, and peer review consistency.

(vi) Reforms to pursue more high-risk, high-reward research

The federal science enterprise developed after World War II has long been the envy of the world. However, as OSTP noted in introducing this RFI, technological and geopolitical shifts demand continuous improvement in how the federal government supports scientific research.

Analysis of publicly available data on federal R&D reveals that much funding flows through relatively small research grants scoped around specific projects. Based on NIH RePORTER data, approximately three-quarters of NIH grants are project-based. This approach may be effective at steadily adding to our body of knowledge, but less effective for developing breakthroughs needed to solve America’s biggest problems.

As with a financial portfolio, a healthy science funding portfolio requires more than one instrument. We can think of incremental project-based grants as bonds; safe, cautious, stable. While these are important to a financial portfolio, a portfolio will grow too slowly if over-invested in bonds. Similarly, to generate breakthrough research that advances national security and economic competitiveness, we must employ different modalities from traditional project-based grants and contracts. Science agencies should explicitly adopt portfolio-based planning for programs and initiatives, and evaluate granting offices (such as NSF directorates or NIH institutes and centers) on portfolio composition.

We do not suggest eliminating project-level grants. Rather, in addition to those grants, the government could expand four funding mechanisms:

- Investigator-based grants. These grants provide large-scale funding for top investigators, enabling exploration and freeing researchers from cautious project scoping. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator Program exemplifies this approach. It has been remarkably successful in advancing biomedical science, producing over 30 Nobel laureates since 1978 and generating breakthrough discoveries like CRISPR genome editing that have transformed medicine and biology. Evidence suggests that its effectiveness is in part because8 it provides scientists freedom to pursue cutting-edge research without constantly pursuing funding or balancing teaching obligations.

- Organization-based grants. Flexible grants to organizations focused on producing knowledge or solving problems within specific domains. These can include focused research organizations (FROs) — nonprofit research organizations dedicated to solving one significant problem. They are large enough to undertake ambitious projects and operate outside university bureaucracy. Organization-based grants can include institutional models similar to the recently announced NSF Tech Labs, which will “support full-time teams of researchers, scientists, and engineers who will enjoy operational autonomy and milestone-based funding as they pursue technical breakthroughs that have the potential to reshape or create entire technology sectors.” IFP has proposed X-Labs as a structure for funding research nonprofits that focus on strengthening different parts of the science ecosystem.

- Fast grants. As described previously, fast grants allow agencies to fund new ideas quickly, enabling investigators to experiment with novel approaches and iterate rapidly.

- Challenges and prizes. These competitions can incentivize numerous ambitious teams to innovate around a common goal, multiplying the potential for breakthrough discoveries. They provide strong incentives to reach important discoveries or develop needed solutions, since payment is often directly tied to results. Because payment is conditioned on winning, these competitions favor ambitious teams that can take on the risk and are often already well-resourced.

Science funding agencies could analyze the scientific enterprise through multiple lenses (e.g., risk profile, institutional type, field, purpose) and strategically plan how different components complement or differ from each other. There is no single correct way to do science, so we should strive for a diversified portfolio where scientists working in different environments, with different constraints and incentives, approach problems from different angles. Beyond varying funding mechanisms, agencies could strategically target different research performers (university, nonprofit research lab, firm, or other entity) based on desired outcomes. As with any well-managed financial portfolio, the federal government should reevaluate and rebalance the federal scientific funding portfolio as metascience units collect evidence on over- and underperforming mechanisms.

(vii) Novel institutional models that complement university structures

One experimental approach within the portfolio described above is to provide more funding to independent research institutions. The dominant project-based grant model is poorly suited to research requiring sustained infrastructure, integrated engineering-science teams, and the continuity that comes from stable institutional support. To fill this structural gap, we have proposed a competitive X-Labs initiative to fund 20–25 independent nonprofit research institutions with approximately $10–50M per year at each of the main federal science agencies: NSF, NIH, and DOE. The concept has gained traction across government, including NSF’s Tech Labs initiative. Policymakers across agencies and in Congress recognize the need for institutional diversity in the federal research portfolio. X-Labs would provide long-term, flexible block grants to organizations outside traditional academic settings.

Independent labs can assemble cross-disciplinary teams under unified leadership, pivot quickly when early data invalidate initial plans, and retain specialized staff scientists who preserve institutional memory. All of these attributes can be difficult for incremental or even large center grants to achieve. Current programs like NIH center grants and NSF research hubs require specifying projects upfront and often end up funding piecemeal collections of individual PIs rather than focused, integrated teams. Institutions like the Arc Institute and Janelia Research Campus, along with older examples like Bell Labs and the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, have produced breakthroughs in part because they operate with a similar framework.

X-Labs makes this institutional format accessible beyond a small set of philanthropic funders. In IFP’s proposed structure, awards would run on seven-year cycles with competitive renewal, providing the long time horizons necessary for ambitious science while maintaining accountability. A suite of award types — including large basic science institutions, execution-focused FROs, regranting organizations that provide innovative small grants, and exploration seed grants — would expand the models available to agencies and lower barriers for non-academic entities. The program can be implemented using Other Transactions Authority, with each agency retaining oversight while coordinating with other agencies that are implementing X-Labs.

Alongside institutional experimentation through X-Labs, federal science agencies should strengthen their capacity for outcome-based funding mechanisms. New offices dedicated to creating well-designed prizes and advance market commitments (AMCs) would signal demand, articulate target product profiles, and create clearer pathways from discovery to impact. When well-scoped and carefully implemented, AMCs and some prizes can incentivize the discovery and commercialization of technologies that would require immense resources or extended timelines if implemented through government grants. Together, institutional block grants and outcome-based funding mechanisms would diversify the research ecosystem while incentivizing more frontier science.

(viii) Advances in AI systems to transform scientific research

While we cannot anticipate all possible AI advances, federal science agencies can be clear-sighted about what scientific problems they want AI to solve. These problems can be incentivized and clearly articulated through grand challenges and evaluations, which have a long and successful history of driving advances in AI. For example, the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition, funded by NIH, defined clear metrics for evaluating progress toward the grand challenge of protein structure prediction. Google DeepMind’s AlphaFold system — widely considered to have solved the problem — depended on CASP as the “gold-standard assessment” for the field. Federal science agencies could commission more scientific AI grand challenges, like CASP, evaluated by clear benchmarks that direct scientific AI efforts within their mission areas. Commissioned benchmarks must be clearly important, technically demanding, address a real gap, and offer the potential to transform a field. The federal government has a clear, valuable role in developing new benchmarks meeting these standards where they do not yet exist.

Federal science agencies should also work to lower barriers standing in the way of new scientific AI models like AlphaFold. AlphaFold, which won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and now undergirds powerful drug design pipelines, exemplifies the power of AI models designed specifically to tackle scientific challenges and trained on scientific data. However, many scientific fields lack the necessary datasets, training, or computational resources to develop new models. Federal science agencies, especially the offices implementing the Genesis Mission at DOE, should focus on overcoming these hurdles in areas where they possess unique datasets, personnel, or supercomputing capabilities, or should target fields not yet mature enough to attract private investment.

Science agencies, especially DOE, could also support autonomous labs. Autonomous labs can generate new datasets at greater speeds, with increased accuracy, and at potentially lower costs than bench scientists, and could be coupled with AI systems for training or testing. Autonomous labs would also release highly trained scientists from rote experimental work, freeing time to develop new hypotheses, experimental approaches, and data analysis methods.

However, agencies should exercise care when structuring opportunities to support autonomous experimentation. Automation inherently requires standardization, which can stifle discovery. Many disruptive discoveries have come from developing new measurement approaches or chasing unexpected findings. Automation should therefore be selectively used to generate data in areas requiring sweeping through large numbers of well-defined parameters. Further, building a one-size-fits-all lab will be nearly impossible for most fields, given the wide variety of experimental conditions and measurement possibilities. Automated labs should be carefully tailored to fit a defined subspace of scientific questions. When supporting these labs, OSTP should coordinate through the interagency Material Genome Initiative (MGI) to create a consortium for self-driving labs, bringing together scientific equipment providers, robotics manufacturers, scientists, and AI developers to develop a roadmap for “Grand Challenges in Autonomous Scientific Discovery.”

Finally, the federal government should support extracting and verifying new natural laws from trained scientific AI models via interpretability efforts. These extracted insights will add to the corpus of scientific knowledge and can be used to generate new hypotheses by both human and agentic AI scientists.

(ix) Statutes, regulations, or policies that create barriers to scientific research

America’s ability to generate groundbreaking scientific discoveries, and to commercialize their practical applications, is hamstrung by rules that discourage top scientific talent from pursuing entrepreneurship or private sector research, keeping foreign-born scientists in exclusively academic jobs.

For example, H-1B visa program rules give academia preferential access to top talent and encourage talented researchers already present in the US to “settle for academia” while awaiting green cards. Not only does the visa impose barriers on academic researchers from taking their talents to the commercial R&D sector, it restricts entrepreneurship, deterring them from spinning out their discoveries into startups that could advance American leadership in critical industries. Furthermore, while the majority (76%) of international graduates from US doctoral programs stay in the US after graduating, growing backlogs for employment-based green cards are reducing stay rates for9 STEM PhD graduates. Together, these barriers impede the deployment of commercial applications that might emerge from federal R&D investments.

To accelerate groundbreaking scientific discoveries and their commercial applications, we recommend the federal government focus on reducing visa delays for international STEM researchers and reducing barriers that encourage them to “settle for academia.” The administration should prioritize visa applications for researchers and entrepreneurs in the critical and emerging technology fields that OSTP and OMB identified as FY 2027 R&D budgetary priorities. This population could include:

- Visa holders employed by one of DOE’s 17 National Labs, the Office of Army Research, the Office of Navy Research, Department of War Laboratories, organizations associated with a designated NSF Engine, Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDCs), or principal investigators at partner universities

- Startup founders in OSTP-identified critical and emerging technology fields with US STEM graduate degrees

- Top researchers in OSTP-identified critical and emerging technology fields

We recommend that the federal government expand mechanisms to prioritize these key personnel for scarce visas, and reduce unnecessary frictions impeding their contributions to American scientific leadership. Reforms should include:

- Expedited processing, consistent with full screening and vetting. OSTP should request expedited processing at consular posts and at USCIS for top talent, including preferential access to interview appointments and adjudications.

- EB-2 prioritization. The administration should clarify that the EB-2 National Interest Waiver (NIW) covers the above populations. This would not change the number of green cards, but would reduce delays and prioritize green cards for top researchers by allowing them to self-sponsor for permanent residency if they are directly contributing to American strength in strategically important fields.

- Exempting relevant R&D talent from certain fees. The government should clarify that the national security exemption laid out in section 1(c) of the President’s September 19 proclamation applies to relevant workers and entrepreneurs in the above categories.

The government has three additional levers to better deploy top talent:

- Building a talent identification function, modeled on Project Paperclip. The US government should systematically identify the world’s top researchers poised to make important defense-relevant contributions in critical fields where China seeks dominance. This includes three components. First, FFRDCs should expand predictive methodologies for identifying top talent poised to make meaningful technical contributions after moving to the US, and to identify talent who pose high security risks. Second, the government should create a formal process to regularly solicit principal investigators throughout the scientific enterprise to report on leading foreign researchers working in defense-related fields on critical and emerging technologies. Third, the government should maintain a regularly updated database of identified talent. A classified report identifying top scientists and technologists, along with screening and vetting details from the intelligence community, should be made available to Congress.

- H-1B Selection. The government can shift H-1Bs away from large outsourcers and toward top R&D talent by modifying its proposed H-1B Weighted Lottery Selection Rule to use actual wages rather than DOL Wage Levels. The consequence of using DOL Wage Levels is that the proposed rule does not prioritize high-skilled occupations, only seniority within an occupation. Under the current proposal, early-career PhD researchers would have lower odds of being awarded an H-1B visa than more senior workers in lower-paying fields like IT services, HR, event planning, or acupuncture. DHS should finalize the rule with weighting based on actual wages rather than DOL Wage Levels, which would prioritize H-1Bs for graduates from US institutions and increase the share going to PhDs. According to a recent report, a pure compensation-based ranking would increase H-1Bs going to PhDs by 148%.

- Augmenting visa processing capacity by piloting AI tools. The overwhelming majority of permanent labor certification filings are approved, but the process can take more than 500 days from start to finish. This leaves highly skilled workers in limbo and deters them from taking promotions or pursuing new research opportunities. The Department of Labor should pilot new AI tools to automate and streamline this process. AI-enabled recommendation algorithms can also augment the screening and vetting of foreign nationals.

-

Fieldhouse, A. J., & Mertens, K. (2024, November, revised). The returns to government R&D: Evidence from U.S. appropriations shocks. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Working Paper No. 2305. https://doi.org/10.24149/wp2305r2

-

Bloom, N., Jones, C. I., Van Reenen, J., & Webb, M. (2020). Are ideas getting harder to find? American Economic Review, 110(4), 1104–1144. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20180338

-

Azoulay, P., & Greenblatt, W. (2025, February). Does peer review penalize scientific risk taking? Evidence from NIH grant renewals (NBER Working Paper No. w33495). https://ssrn.com/abstract=5140742

-

Matthews, K. R. W., Calhoun, K. M., Lo, N., & Ho, V. (2011). The aging of biomedical research in the United States. PLOS ONE, 6(12). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0029738

-

Schneider, S. L., et al. (2020). 2018 FDP faculty workload survey: Research report: Primary findings. Federal Demonstration Partnership. https://thefdp.org/wp-content/uploads/FDP-FWS-2018-Primary-Report.pdf

-

Azoulay, P., Fuchs, E., Goldstein, A. P., & Kearney, M. (2010). Funding breakthrough research: Promises and challenges of the “ARPA model”. Innovation Policy and the Economy, 19. https://doi.org/10.1086/699933

-

Carson, R. T., Graff Zivin, J. S., & Shrader, J. G. (2023, June). Choose your moments: Peer review and scientific risk taking (NBER Working Paper No. 31409). https://www.nber.org/papers/w31409

-

Azoulay, P., Graff Zivin, J. S., & Manso, G. (2011). Incentives and creativity: Evidence from the academic life sciences. RAND Journal of Economics, 42(3), 527–554. https://doi.org/10.3386/w15466

-

Kahn, S., & MacGarvie, M. (2020). The impact of permanent residency delays for STEM PhDs: Who leaves and why. Research Policy, 49(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103879