- Download PDF

-

- Executive summary

- What are the NVIDIA H200 and H100 chips?

- How do the H200 and H100 chips compare to other advanced NVIDIA AI chips?

- Hopper chips remain important for frontier AI

- H200 or H100 exports would substantially add to China’s supply of advanced AI compute

- H200s outperform any AI chip legally available in China

- Selling H200s or H100s to China would erode America’s compute advantage

- Maintaining a compute advantage is critical for the United States’ AI competitiveness

- Appendix 1: Assessing 30x performance improvement claims from Blackwell chips

- Appendix 2: H200 cluster-level performance analysis

- Appendix 3: On measuring performance across generations of chips: FP4 vs. FP8 FLOP/s vs. TPP

- Appendix 4: Estimating installed Hopper chips by year-end 2025

Editor’s note: Shortly after this piece was published, Semafor reported that the Commerce Department will allow exports of the H200 chip to China. This report analyzes the consequences of exports of H200s at different quantities.

Executive summary

Last month, the Trump administration decided not to export a version of NVIDIA’s flagship Blackwell AI chips (such as the rumored “B30A” chip) to the People’s Republic of China (henceforth “China”), with President Trump stating “We will not let anybody have [the most advanced AI chips] other than the United States.”1 Now, the administration is expected to convene a high-level meeting to decide whether to authorize the export of NVIDIA’s H200 chips to China.

Released in March 2024, the H200 is NVIDIA’s best AI chip from the previous “Hopper” generation and is an upgraded version of the H100 chip. Much like cutting-edge Blackwell chips, Hoppers use TSMC’s 4nm manufacturing process technology. Despite being a previous-generation AI chip, the H200 and the H100 will likely be highly useful for frontier AI workloads throughout 2026:

- As of December 2025, 18 of the 20 most powerful publicly documented GPU clusters in the world primarily used Hopper chips, including all of the top 7. Hoppers currently represent just over half as much installed AI compute as Blackwells.2

- Previous generations of AI chips have remained in use for frontier model training for roughly four years. If this trend holds for Hoppers, they will likely be used for frontier training throughout 2026 — especially the H200, which was released in late 2024.

Permitting export of meaningful volumes of advanced Hopper chips to China would have six key implications:

- The decision would be a substantial departure from the Trump administration’s current export control strategy, which seeks to deny powerful AI compute to strategic rivals. The H200 would be almost 6x as powerful as the H20 — a chip that requires an export license to China and has been approved for export in only limited quantities.

- China would have access to chips that outperform any chip its companies can domestically produce, and at much higher quantities. Huawei is not planning to produce an AI chip matching the H200 until Q4 2027 at the earliest.3 Even if this timeline holds, China’s severe chip manufacturing bottlenecks mean that it will not be able to produce these chips at scale, reaching only 1–4% of US production in 2025 and 1–2% in 2026.4

- Chinese AI labs would be able to build AI supercomputers that achieve performance similar to top US AI supercomputers, albeit at a cost premium of roughly 50% for training and 1-5x for inference, depending on workload. Blackwells have been marketed as delivering 30x the inference performance of the H200. However, this multiplier does not account for price differences and reflects best-case assumptions for Blackwell-based clusters and worst-case assumptions for Hopper-based clusters. In an apples-to-apples analysis, we estimate near parity between Blackwells and H200s for many inference workloads; up to a 5x advantage for Blackwells on the type of inference workloads for which they are best suited; and a 1.5x advantage for Blackwell-based clusters in training. This means that with access to Hoppers, Chinese labs could build AI training supercomputers as capable as American ones at 50% extra cost5 — a premium that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) would likely at least partly subsidize. The Blackwell advantages could increase if AI developers can exploit its advanced “low-precision” features,6 which some might do in 2026, but there is not yet evidence that any have done so at scale.

- These exports would counterfactually add to China’s total supply of advanced AI compute, and would likely do little to slow China’s indigenization efforts. China’s chip manufacturing bottlenecks mean Huawei’s peak production will still fall well short of domestic demand. Therefore, US chip sales would add to China’s total compute, not substitute for domestic production. Beijing will also likely maintain artificial demand for domestic chips through procurement mandates and restrictions on foreign chips in critical infrastructure, boosting its domestic semiconductor industry regardless of US export control policy.

- As summarized in Figure 1, exporting Hopper chips would significantly erode America’s expected AI compute advantage over China. With no AI chip exports to China and no smuggling, we estimate the US would hold a 21–49x advantage in 2026-produced AI compute, depending on whether FP4 or FP8 performance is used for Blackwell chips.7 This advantage would translate into a much greater American capacity to train frontier models, support more and better-resourced AI and cloud companies, and run more powerful inference workloads for more capable AI models and agents. Unrestricted H200 exports would shrink this advantage to between 6.7x and 1.2x, depending on the scale of Chinese demand and the degree of adoption of FP4.8

- If supply is constrained, producing Hoppers for China would directly trade off with Blackwell production for the US and allies, since both chip generations compete for much of the same high-bandwidth memory (HBM), logic, and advanced packaging capacity.

We focus on the H200 chip in this report because it is currently under consideration for export to China. But because the H200 chip is essentially a memory-heavy version of the H100 chip, the conclusions drawn in this report largely also apply to H100 chips.9

What are the NVIDIA H200 and H100 chips?

The NVIDIA H200 and H100 chips are data center AI chips released in 2024 and 2022, respectively. Both of these chips are advanced chips belonging to the previous Hopper generation,10 which still power some of America’s largest AI data centers. Both chips contain one GH100 logic die. The difference is that the H100 contains five high-bandwidth memory (HBM) stacks while the H200 contains six stacks using more advanced HBM, therefore achieving superior AI inference performance.11 Both chips exceed current export control thresholds on total processing performance (TPP) by almost 10x.12

How do the H200 and H100 chips compare to other advanced NVIDIA AI chips?

Table 1 below compares the H200 and H100 chips’ specifications, price, and price-performance to those of other AI chips central to current US export control debates:

- The B300, the flagship Blackwell chip;

- The B30A, which President Trump denied to China in recent trade negotiations,13 and

- The H20, a downgraded Hopper chip designed specifically to comply with export control thresholds that the administration announced earlier this year it would approve for sales.

Figure 2 compares the specifications of each of the advanced AI chips that have recently been considered for export approval to China.

When considering FP4 performance, Blackwells are substantially more powerful than Hopper chips on raw, per-chip processing power. However, in cases where chips can be networked in similar configurations, per-chip metrics have limited strategic relevance, as chips can be networked into clusters to achieve desired levels of aggregate performance. At the cluster level, what matters most is how much performance a user can obtain per dollar spent — or “price-performance.” As we discuss below, by this metric, advanced Hopper chips are highly competitive with Blackwells, achieving ~70% of Blackwell price-performance for training, and variable inference competitiveness depending on workload.

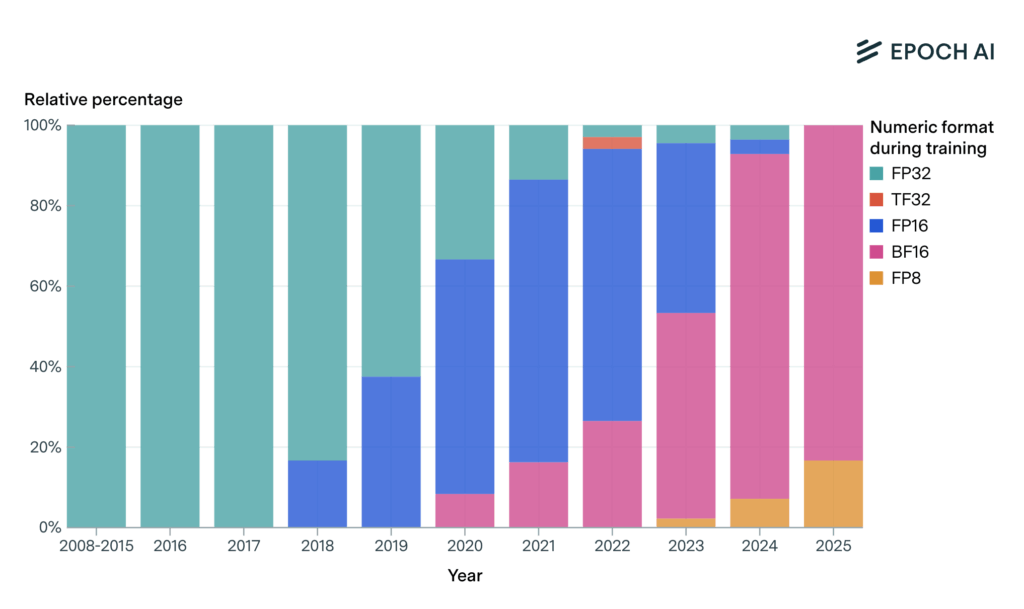

Box 1: FP4 vs. FP8

One key way that Blackwells differ from Hoppers is the “number formats” they support when performing calculations. A number format describes the quantity of memory “bits” used to store each number, and how those bits are used. Common number formats include FP4, FP8, and FP16, which use 4, 8, and 16 bits to store numbers, respectively. Each reduction in bits increases performance, typically at the expense of more calculation errors. Blackwells support as low as FP4 calculations, but Hoppers only support down to FP8 calculations.

Different number format availability across different chips complicates assessing chip comparative performance because comparisons between different formats are not apples-to-apples.

In this analysis, we often use FP8, as opposed to FP4, as a primary comparison point when discussing AI training, AI inference, and general chip performance. This is because even for Blackwells, FP8 is more commonly used by frontier AI labs. Most AI training likely does not yet leverage FP4. And even where AI companies today use FP4 models for inference, Hopper chips can run these models by using FP4 to represent model weights, but FP8 to make calculations. This results in similar performance gains to Blackwell chips for part (though not necessarily all) of the inference workflow. Therefore, using FP4 performance for Blackwells inflates the Blackwells’ real AI training and inference performance relative to Hoppers.14 However, we also present FP4 results given FP4’s early use today, and likely increasing usage in the future.

A more detailed discussion comparing these performance metrics is provided in Appendix 3.

Drawing from the specifications listed in Table 1, we find that:

- The H200 achieves similar memory bandwidth price-performance to the B300. This metric is most relevant for inference, which is usually bottlenecked by memory bandwidth rather than processing capability. This performance comparison remains the same whether the workload is run in FP4 or FP8.

- The H200 achieves 70% of the B300’s price-performance for tera floating-point operations per second (TFLOP/s) output at FP8. This metric is most relevant for training, which is typically bottlenecked by available processing capability, not memory bandwidth. Given the enormous cost of training large AI models, model developers ideally want the most cost-effective training compute possible. This price-performance estimate relies on FP8 performance rather than FP4 because, at least for now, FP4 is not yet known to be used by frontier AI companies for training large models in a way that benefits from Blackwell’s FP4 FLOP/s premium (see Box 1 and Appendix 3 for details).

At face value, these relatively modest performance differences seem to contradict NVIDIA’s marketing, which claims that Blackwell chips (specifically the B200) achieve 30x better inference performance than the H200. But NVIDIA’s 30x advantage claim reflects a best-case scenario for Blackwell-based clusters, and a worst-case scenario for Hopper-based clusters. After adjusting for these considerations, the H200 is nearly as cost-effective for most inference workloads. More specifically:

- NVIDIA assumes the Blackwell operates on FP4 models and the H200 on FP8 models. However, the H200 can still run FP4-based models and achieve enhanced inference performance, despite lacking native FP4 math capability. But for part of the inference workflow and for some models and use cases, some AI labs are now exploring how to leverage Blackwell’s FP4 math capability.15 See Box 1 above for further details.

- Blackwells can be installed in larger and higher-bandwidth networks than H200s, improving inference performance for certain workloads. But most workloads do not require such large networks, and it may even be possible to configure H200s in equivalent networks, eliminating this benefit for all inference workloads.

- The 30x advantage claim is on a per-GPU basis, but H200s are cheaper than B200s, meaning the difference can readily be made up by simply buying more H200s. To make for a proper comparison, the advantage needs to be adjusted to account for price-performance.

For more details on each of these points, see Appendix 1.

For AI training, a cluster-level analysis (Figure 3) finds that Chinese AI labs could use H200s to build AI-training FP8 supercomputers as powerful as those available to US AI labs for around 50% extra cost. See Appendix 2 for the specifics of these calculations. This is a higher cost penalty than the 20% extra cost we calculated for B30A chips in our Blackwell report. The Chinese government would likely subsidize at least some of this cost difference, in line with state subsidies for China’s semiconductor industry (discussed in further detail below).

Hopper chips remain important for frontier AI

Hopper chips are still a relatively advanced AI chip. Like the most recent Blackwell design architecture, they are manufactured using TSMC’s 4nm process and remain important for frontier AI training and inference, even as Blackwells power the largest planned cluster buildouts. As of December 2025, 18 of the 20 most powerful publicly documented GPU clusters in the world primarily used Hopper chips, including all of the top 7. As of June 2025, Hoppers represented the majority of xAI’s “Colossus” fleet, with 150,000 H100s, 50,000 H200s, and 30,000 GB200 chips. Adjusting these numbers based on processing performance (FP8 FLOP/s), Hoppers made up over 70% of Colossus’ total computing power.16

By the end of 2025, Blackwells will likely have overtaken Hoppers in terms of total installed computing power worldwide. We estimate that Hoppers will make up slightly over a third of the total installed base of Blackwells and Hoppers.17

When will Hoppers cease to be relevant for frontier AI? Recent generations of AI chips have been used to train frontier models for roughly four years on average. If this trend holds for Hopper chips, they should remain relevant for frontier AI training throughout 2026. Indeed, as illustrated in Figure 4, the majority of recently published frontier models were trained with Hopper chips, and no published models have yet been known to have been trained with Blackwells, though naturally this will change in 2026. The H200 in particular was only released in March 2024, so may be used for frontier AI applications well beyond 2026.

However, in contrast to its recent 2-3 year release cycle, NVIDIA has accelerated to roughly one new generation per year, with the Blackwell line released earlier this year and the next Vera Rubin line expected in late 2026. This faster release cycle makes it likely that, in the future, leading AI chip designs will be used for training frontier AI models for shorter periods than the currently typical four years. But this does not mean that Hopper-series chips — especially H100s and H200s — will become legacy AI chips anytime soon, particularly in light of their superiority to what will otherwise be available in China. Exports of the H200 would offer China substantially better AI training and inference capabilities than what is currently available on the Chinese market.

H200 or H100 exports would substantially add to China’s supply of advanced AI compute

Exporting large quantities of Hopper chips would directly add to China’s total supply of advanced compute, which currently lags that of the United States due to tight manufacturing bottlenecks (see Figure 5 below). Based on China’s extremely limited domestic production capacity for advanced AI processor dies and HBM stacks — essential components for AI chips — we previously estimated that China’s output of AI chips will reach only 1–4% of US production in 2025 and 1–2% in 2026.18

Because China cannot manufacture enough AI chips to meet demand, any chips the US sells are unlikely to substitute for domestic production. Instead, they would likely add directly to China’s total advanced AI compute capacity. Selling Hopper chips would thus hand China advanced AI compute it has no other way to acquire.

At the same time, Beijing is likely to generate artificial demand for the domestic chips that Huawei and other Chinese companies can produce. This already occurs through restrictions on US AI chip imports used in critical infrastructure. In recent months, Chinese regulators have banned imports of the H20 and RTX 6000D (another downgraded NVIDIA chip), ostensibly to promote adoption of domestic alternatives.19 Yet for more advanced AI chips like the H200, for which China has no competitor and has imposed no restrictions, Chinese AI companies will remain highly incentivized to purchase significant volumes.

Hopper sales, however, would likely do little to deter China from its long-term goal of achieving self-sufficiency in advanced AI chip manufacturing. On the contrary, recognizing their strategic vulnerability, Chinese chipmakers are ramping up production, aided by government subsidies. SemiAnalysis forecasts that Chinese foundry SMIC will increase die production for Huawei Ascends by ~2.75x between Q1 and Q4 of 2026. Allowing Hopper sales is unlikely to result in the CCP and Chinese companies scaling back these chipmaking efforts, and thus would instead contribute to China’s total available compute.

H200s outperform any AI chip legally available in China

Even if China could manufacture chips at scale, its current chip designs remain less competitive than the H200. According to its recent three-year roadmap, Huawei is not planning to produce an AI chip competitive to the H200 until Q4 of 2027 at the earliest. In the meantime, the H200 outperforms any chip produced in China: compared to China’s best chip, the Huawei Ascend 910C, the H200 provides ~32% higher processing power20 — a key determinant of AI training performance — and 50% more memory bandwidth — the main determinant of inference performance. On price-performance, H200s offer a roughly 16% advantage over the 910C for processing and a 32% advantage for memory bandwidth.

As we note in our Blackwell report, the performance gap between NVIDIA and Huawei chips is even wider in practice than these theoretical performance specs suggest. Huawei’s chips are less reliable than US alternatives, as they run on software that is prone to malfunction and hard to fix, especially when scaled into larger clusters. As a consequence, Chinese AI models are trained overwhelmingly on American chips.

Selling H200s or H100s to China would erode America’s compute advantage

Building on our assessment of the impacts of Blackwell exports, we find that H200/H100 exports across nine scenarios would erode the US advantage over China in 2026-produced AI compute, though less severely.

The analysis relies on the same assumptions as the Blackwell assessment, with three major exceptions:

- First, China’s demand is lower due to the H200-based FP8 training clusters being 70% as price-performant as B300-based FP8 training clusters (see Figure 3).21 This means that in each scenario, we assume 1) China spends the same amount, but this buys 70% of the compute it would have relative to the Blackwell case as a baseline, and 2) the Chinese government is willing to provide fewer subsidies — up to $15 billion in each scenario. 22

- Second, in H200 export scenarios, we assume China smuggles some Blackwells, unlike in the B30A exports case, where China would have no need to smuggle if Blackwell exports were legal. As in the B30A case, we assume that US compute advantage is reduced in cases where chip supply is inelastic. This is because steady demand for Hopper chips could encourage manufacturers to shift production capacity away from Blackwells intended for the United States and allies, in order to produce more Hopper chips for China.23

- Third, we break down each scenario based on whether AI companies can usefully exploit FP4 acceleration. To do so, we measure compute in FLOP/s equivalents of B300s operating at FP8. That means, for example, that if FP4 becomes available, then the B300 FP8 FLOP/s-equivalent of a B300 increases by 3x to account for the B300’s 3x FLOP/s at FP4 vs. FP8. US and partner companies, with superior access to Blackwells, gain a much greater advantage from FP4 capabilities than China, as China is limited to Huawei chips and Hoppers, both of which cannot support 4-bit computation. China gains FP4 acceleration only from its smuggled Blackwells.24

Given these assumptions, as shown in Figure 6, we find that with no smuggling, the United States would obtain 21-49x more 2026-produced AI computing power than China. If H200s are instead approved with no quantity limits, this advantage shrinks to between 4.0x and 1.3x. This assumes that US AI companies are using Blackwell’s FP4 capability at scale. However, if US AI companies were to exploit increased Blackwell FP4 processing capacity, which they are exploring in 2026, unrestricted H200 exports would adjust the advantage to between 6.7x and 2.1x. This is because an H200-based FP8 training cluster is 20% as price-performant as a B300-based FP8 training cluster (see Figure 3). In reality, US AI companies may partially exploit Blackwell FP4 capabilities, putting the US advantage between these estimates. These results are moderately more favorable to the United States than B30A exports, which would have eroded the US advantage to 4.0x in a conservative scenario and given China a 1.1x advantage in an aggressive exports scenario.25

Maintaining a compute advantage is critical for the United States’ AI competitiveness

Ensuring that the United States retains the largest possible advantage in advanced AI compute over China pays several dividends for its long-term competitiveness in AI development and deployment. A large compute advantage allows for:

- Training the next generation of American frontier models, thereby extending the US lead over China in model quality. A larger compute base also supports a wider range of AI R&D efforts, enabling US companies to experiment with new architectures and training approaches.

- Hosting more and better-resourced frontier AI companies than China, each of which depends on substantial access to compute. This includes US cloud providers, for whom compute availability is essential to maintaining global market share. By contrast, exporting Hoppers to China would increase Chinese cloud providers’ ability to serve cloud compute in China and abroad, eroding US cloud companies’ market share. In a worst-case scenario where Hopper exports were large enough to exceed Chinese domestic demand, Chinese cloud companies could serve foreign customers as well, cannibalizing US cloud providers’ global market share and undermining the Trump administration’s efforts to export the American AI stack.

- Inferencing more AI models, including answering more AI model queries and applying more inference-time compute per query. Larger pools of inference compute enable deeper model reasoning, more capable AI agents, and thus more powerful deployed AI systems. To the extent that AI systems will increasingly be used to accelerate AI R&D itself, maintaining a strong lead in total inference compute could be the key to maintaining a larger lead in frontier AI capabilities.

Ultimately, American AI competitiveness depends not only on withholding the most cutting-edge AI chips from strategic adversaries — as President Trump did by refusing to export Blackwells — but also on preserving the aggregate volume of compute that underpins US AI leadership. Exports of H200s or H100s to China would directly erode that compute advantage, even if cutting-edge Blackwells remain restricted.

Appendix 1: Assessing 30x performance improvement claims from Blackwell chips

NVIDIA markets the GB200 as achieving a 30x performance improvement versus the H200. However, this improvement represents a best-case scenario that rarely applies in the real world. The GB200’s advantages can be decomposed into several factors to generate its true price-performance advantage over the H200 across most workloads:

Relative to the 30x scenario, the GB200’s advantage should be adjusted 2x downward since AI companies are yet to exploit Blackwell’s FP4 capability at scale.

- The GB200 and GB300 achieve 10,000 and 15,000 FLOP/s at FP4, respectively, and both achieve 5,000 FLOP/s at FP8, while the H200 lacks FP4 capability and achieves 1,979 FLOP/s at FP8. Dropping available FLOP/s of the GB200 to the FP8 specification cuts the claimed performance gain by 2x.

Relative to the 30x scenario, GB200s should be adjusted by as much as 6x downward due to greater processing performance utilization in better networked H200 computing clusters and/or workloads not involving highly-interactive large mixture-of-experts (MoE) models.

- The workload benchmarked in the 30x scenario requires tight networking across a large number of AI chips, with a large MoE model executing a “high interactivity” workload, i.e., one that requires fast interaction between the AI system and a user or other system. GB200/GB300 systems are highly optimized for this workload, as they connect 72 Blackwell chips together with a high-bandwidth interconnect called NVLink.26 By comparison, the H200 is limited to an 8-chip NVLink domain. As a result, NVIDIA reports a 3.5x drop in utilization of processing performance capacity in the H200 as clusters are expanded beyond 8 chips and up to 64 chip clusters with poor networking.27 However, in 2023, NVIDIA marketed the Hopper-class NVLink Switch as more generally supporting NVLink domains with 256 Hopper chips, with each switch having 64 ports for Hopper-chip connections, thus eliminating this networking loss. One product leveraging this capability was the DGX GH200, a system of 256 H200s interconnected via NVLink. Adjusting for this enhanced H200 networking capability shrinks the Blackwell advantage by a further 3.5x.

- The DGX GH200 appears not to be currently sold, suggesting this capability is not available today, and NVIDIA now markets the same Hopper-class NVLink Switch as supporting NVLink domains with only 8 Hopper chips, speculatively by disabling firmware support for larger domains. However, given the Hopper architecture’s latent capability, and particularly with servicing support, China may be able to configure H200s, combined with non-export-controlled networking equipment (e.g., NVLink Switches), to work in large NVLink domains. This scenario has precedent. In 2020, Google configured even older NVIDIA A100 chips to operate in a 16-A100 NVLink domain by networking two 8-A100 systems.

- Furthermore, most workloads do not require tight networking with large NVLink domains. First, NVIDIA’s finding is limited to inference; most training workloads do not require large NVLink domains.28 Second, even many inference workloads do not suffer this penalty. In conversations with IFP, industry experts noted that there are minimal to no NVLink-related penalties for inference of dense models or small mixture-of-experts (MoE) models.29 Even large MoE models do not suffer this penalty for low interactivity workloads; NVIDIA found that the GB200’s 30x performance boost drops to 5x at lower interactivity (4 output tokens per second (OTPS)) when inferencing a GPT-4-class MoE, suggesting a 6x performance boost (30x divided by 5x). Furthermore, in conversations with IFP, industry experts noted that a commercially standard interactivity for a frontier MoE may range from 70 OTPS to in the 200s. For many MoEs, major networking-driven interactivity penalties only appear for an OTPS above 300. Such penalties appear at lower interactivities for NVIDIA’s benchmarked GPT-4-class MoE (suggesting again how the 30x claim is a best-case scenario). But even for models such as GPT-4, AI companies can choose low-interactivity inference while achieving organizational goals. In this scenario, the claimed performance gain drops by 6x.

Finally, relative to the 30x scenario, the GB200s advantage should be further adjusted 2.5x downward to account for price-performance.

- The H200 chip achieves similar inference price-performance as a Blackwell chip, measured by memory bandwidth per dollar. We use memory bandwidth per dollar as the key measure in this case because the stated 30x performance increase is specifically for AI inference, not training.

As a result, the price-performance of an H200 achieves near parity with GB200s or GB300s for inference.

- The 2x (adjusting for FP4), 3.5x (adjusting for networking), and 2.5x (adjusting for price-performance) factors, multiplied together, yield an 18x adjustment. Dividing the original 30x advantage by 18x leaves the GB200 with only a 1.7x advantage over the H200, compared to the original 30x claim. This estimate is further corroborated by NVIDIA’s benchmarking, at the same interactivity of 20 tokens per second, of the H200 with a B200 operation at FP8 without a large NVLink domain. NVIDIA finds a 4.3x boost with the B200, which becomes 1.7x after incorporating the 2.5x downward adjustment for price-performance.30

- Even for cases where the H200 is not networked beyond an 8-chip NVLink domain, real-life penalties are lower. For low-interactivity workloads, the networking adjustment changes from 3.5x to 6x, giving the GB200 equal price-performance relative to the H200, compared to the original 30x claim. However, for an average large frontier MoE inference workload where the H200 is not networked into a large NVLink domain, industry experts told IFP that typical large MoEs with commercially typical levels of interactivity would incur an H200 price-performance penalty of 2.5–5x.

Appendix 2: H200 cluster-level performance analysis

At the cluster-level, we estimate that Chinese AI labs could use H200s to build AI supercomputers as powerful as those available to US AI labs, at around 50% extra cost. Note that these numbers should be taken only as high-level estimates.

To arrive at these numbers, we analyze the amortized cost clusters of equivalent FLOP/s performance to a B300 cluster operating at FP8. We use FP8 as a standard reference point given that FP8 is likely to remain the norm for AI training for the foreseeable future (see Appendix 3 for more discussion). We compare this reference cluster against costs for clusters using the following AI chips:

- B300s operating at FP4

- B200s operating at both FP4 and FP8

- H200s operating at FP8

- A100s operating at FP16 – a previous generation NVIDIA AI chip, which still requires an export license to ship to countries of concern

- V100s operating at FP16 – an older NVIDIA AI chip, which does not require an export license

We make the following assumptions:

- In each case, we are using the 8-GPU server configuration. Note, however, that B300s, B200s, and H200s can be further scaled up to larger networks (See Appendix 1 for further discussion). We assume that cluster-level price performance differences do not vary substantially as the NVLink domain is scaled; e.g., that these results roughly hold when comparing 72-GPU NVLink domain-based systems for B300s and H200s.

- The servers under consideration have the following performance and price specifications:

- B300 servers

- B200 servers

- H200 servers

- A100 servers

- V100 servers

- Relative cloud rental costs between different servers mirror the relative capital costs of acquiring those same servers.

- In each case, we use a variant of a fat-tree network topology (typical for AI clusters), where networking costs scale linearly with the number of accelerators, with discrete increases in networking costs as we add more switching tiers. In addition, we assume that the cost of networking hardware on a per-device basis (network switches, transceivers, cables) does not vary significantly across each of the clusters we consider.

Based on data from Epoch AI analyzing 41 clusters used to train frontier models, we can derive overall cost differences by further assuming that for our reference cluster, 71% of amortized cluster capital expenditures is server hardware costs, 19% is server-to-server networking hardware costs, and 10% is energy costs. The calculations to obtain relative cost differences based on these assumptions and data can be found here.

Appendix 3: On measuring performance across generations of chips: FP4 vs. FP8 FLOP/s vs. TPP

AI chips operate at different number formats, which describe the quantity of memory “bits” used to store each number, and how those bits are used. This leads to differences in performance measurements depending on which number format is used.

- Common number formats include FP4, FP8, and FP16, which use 4, 8, and 16 bits to store numbers, respectively. Each reduction in bits increases performance, typically at the expense of more calculation errors.31

- The lowest number format that Blackwells support is FP4, whereas for Hoppers it is FP8.

- The Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) uses Total Processing Performance (TPP) as a standard measure to assess AI chip processing performance for the purposes of determining which chips are subject to export controls. TPP multiplies the number of bits in a number format by the associated FLOP/s performance, providing a generalized definition across chips that operate with different number formats.32 However, TPP can produce misleading comparisons between chips of different generations, such as Blackwells and Hoppers, because it treats FLOP/s using different number formats (e.g., FP4 vs. FP8) as directly comparable. This is not the case for many AI workloads.

For AI training, FP8 is currently the leading training format; AI companies are beginning to use FP4 as a successor format, but not yet in ways that exploit Blackwell’s disproportionate FP4 processing performance advantage.

- Choosing the right format represents a trade-off between two factors. On the one hand, the same chip typically provides more processing performance at a lower bit format, enabling greater training compute and thus unlocking more model capability according to compute scaling laws. On the other hand, lower bit formats encode less information, thus degrading the quality of the model and its outputs.

- As recently as a year ago, research showed that 7–8 bit formats such as FP8 represented the optimal balance for training. As a result, no flagship models are known to have been trained using FP4 as of this year; in 2025, even 8-bit training is still in early adoption, with most models trained using older 16-bit formats.

Figure 7: Percentage of notable AI models trained with different number formats over time33

- However, in its Blackwell chips released in the past year, NVIDIA introduced a specialized FP4 format called “NVFP4,” with NVIDIA’s early research suggesting a new optimal balance for training, with a small, 12-billion parameter model by avoiding significant degradation of model quality and outputs relative to FP8 training.34

- As Blackwells get deployed more widely, more companies – especially frontier companies, which would gain the most cost savings by using FP4 – may attempt to leverage FP4 for training. Among frontier AI developers, Google and Anthropic have chosen not to do so, given their respective use of Tensor Processing Units and Amazon Tranium chips, which do not support 4-bit training. On the other hand, OpenAI, xAI, and Meta rely on NVIDIA chips, which support FP4.

- However, in conversations with industry experts, IFP learned that, thus far, AI companies are not using FP4 to unlock additional FP4 Blackwell processing performance for training AI models. For example, OpenAI’s use of FP4 training for its GPT-OSS model involved mixed-precision (i.e., part of the math uses higher than 4 bits), meaning only NVIDIA FP8 engines can be used for training, not FP4 engines.

- According to industry experts IFP spoke with, it is an open question whether AI companies will figure out how to effectively use pure FP4 math for training in a way that can leverage extra FP4 Blackwell processing performance. This analysis suggests that comparing FP4 FLOP/s on Blackwell chips to FP8 FLOP/s on Hopper chips may overstate Blackwell’s training advantage in practice, but in the future, Blackwell’s FP4 capability may provide a training performance advantage for some models.

For AI inference, AI companies are also beginning to deploy FP4, but such uses may only partially exploit Blackwell’s FP4 processing performance advantage.

- AI inference involves two steps: “prefill,” which pre-processes model input queries, and “decode,” which generates model output tokens.

- The prefill stage requires a high ratio of processing performance to memory bandwidth; therefore, it is usually bottlenecked by a chip’s available processing performance. Here, AI companies are attempting to move to pure FP4 model weights that can benefit from Blackwell’s extra FP4 FLOP/s, but like in the training case, models such as OpenAI’s GPT-OSS leverage mixed-precision only partially leveraging FP4, so they must use lower-performance, higher-bit Blackwell capability to run these models.

- The decode stage introduces additional challenges. Like with prefill, mixed-precision weights can prevent the use of Blackwells’ FP4 acceleration in the decode stage. However, unlike prefill, decode requires a high ratio of memory bandwidth to processing performance and is therefore generally memory-bound, so chips typically underutilize their processing performance. This is because of limitations in the way inference workloads can be parallelized.35 Using FP4 model weights halves the memory storage and bandwidth requirements per model parameter, relaxing the memory bottleneck and allowing double the inference processing performance utilization. However, Hopper FP8 engines can also run FP4 model weights and gain the same increased processing performance utilization as Blackwell FP4 engines, meaning Blackwell FP4 acceleration does not provide an improvement.36

- This analysis suggests that comparing FP4 FLOP/s on Blackwell chips to FP8 FLOP/s on Hopper chips may overstate Blackwell’s inference advantage in practice, but in the future Blackwell’s FP4 capability will likely provide a more meaningful inference performance premium in some cases.

Appendix 4: Estimating installed Hopper chips by year-end 2025

We estimate that, by the end of 2025, Hoppers will represent roughly 54% as much installed AI compute as Blackwells or just over a third of the total installed base of Blackwells and Hoppers combined.

Blackwells: By the end of 2025, IFP previously estimated that 3.1 million Blackwell chips will be installed.

Hoppers: By the end of 2025, roughly 3.56 million Hopper H100s, H200s, and H800s will have been installed worldwide, in addition to about 1.46 million H20s. To get these figures, we make the following estimates for Hoppers installed each year:

- 2023 and earlier. We estimate that 900,000 H100s and H800s were installed up to 2023, based on data from Epoch AI (H200s and H20s were not yet sold in 2023).

- 2024. NVIDIA produced 3.5 million Hoppers in 2024. SemiAnalysis estimated that NVIDIA produced 1 million H20s that year. This suggests that the remaining Hoppers were 2.5 million H100s and H200s, as H800s were no longer sold in 2024.

- 2025. We estimate NVIDIA produced 460,000 H20s, based on sales of $5.25 billion (across Q1 and Q2) at a price of $11,500. Finally, we estimate NVIDIA produced 160,000 H100s and H200s, which we find by assuming 20% of NVIDIA chips produced in 2025 are Hoppers, and the 2025 H20 and Blackwell production numbers above.

Using FP8 performance (see Appendix 3 for why), we calculate:

- 7.05 FP8 ZFLOP/s (zettaflops per second) for H100s, H200s, and H800s (3.56M chips * 1,979 FP8 TFLOP/s/chip);

- 0.432 FP8 ZFLOP/s for H20s (1.46M chips * 296 FP8 TFLOP/s/chip), and;

- 13.95 ZFLOP/s for Blackwells (3.1M chips * 4,500 FP8 TFLOP/s/chip average).37

This means that total Hopper ZFLOP/s (including H20s) equals 7.48 ZFLOP/s, and the total Blackwell and Hopper 2025 installed base equals 21.43 ZFLOP/s. Dividing Hopper ZFLOP/s by Blackwell ZFLOP/s yields 54%. Additionally, dividing 7.48 ZFLOP/s by 21.43 ZFLOP/s to get the Hopper share of the total Blackwell and Hopper installed base yields 35% — or slightly over a third.

-

We assessed the impacts of Blackwell exports to China in our report “Should the US Sell Blackwell Chips to China?”

-

See Appendix 4 for details. As of June 2025, for instance, Hoppers represented over 70% of xAI's Colossus fleet computing power.

-

According to Huawei’s 3-year Ascend chip roadmap.

-

Conditional on the US and allies maintaining and strengthening China-wide export controls on key semiconductor manufacturing equipment like extreme ultraviolet (EUV) and deep ultraviolet (DUV) immersion photolithography tools, as well as deposition, etch, process control, and other tools.

-

As opposed to the 20% extra cost we calculated for the B30A AI chip, which the Trump Administration denied to China in recent trade negotiations. See Appendix 2 for details.

-

This refers to the Blackwell’s capability to perform computations in a 4-bit floating number format (FP4).

-

The finding of a 21-49x advantage with no US exports or smuggling is consistent with the 31x finding in our previous B30A report, which was measured by a single “Total Processing Performance” (TPP) metric, but now becomes a range based on degree of adoption of Blackwell’s FP4 features. More realistically, AI companies will partially adopt some advanced Blackwell features, putting the US advantage after H200 exports somewhere in the middle of these estimates. See Appendix 3 for further discussion.

-

These results are moderately more favorable to the United States than Blackwell sales, which would have eroded the US advantage to 4.0x in a conservative exports scenario and tipped the compute balance slightly in China’s favor in an aggres

sive exports scenario.

-

In particular, because our compute advantage forecasts (Figure 1) rely on chip processing performance, and H100s and H200s have the same processing performance, the impact of exporting either of these chips on total compute would be unchanged.

-

The Hopper generation also includes the discontinued H800s, as well as the H20s. H20s have significantly degraded processing performance but are highly competitive in price-performance terms for some inference workloads.

-

The H200 uses HBM3e rather than the H100’s HBM3, providing a 40% boost in memory bandwidth and double the memory storage capacity, key determinants of AI inference performance. HBM3e is the same memory technology that cutting-edge Blackwell chips use. Because of this high-bandwidth memory (HBM) upgrade, NVIDIA reports that the H200 can provide up to 2x the large language model (LLM) inference performance of the H100 chip. For some workloads, such as inference of Meta’s Llama 2 70B model, memory is the bottleneck in the H100 because model storage leaves little space left in the key-value (KV) cache, which limits the ability of the H100 to batch user requests (i.e., run more user requests in parallel). The extra memory in the H200 relieves this memory storage bottleneck, doubling throughput. For the purposes of comparing Blackwell chips and the H200, memory storage is less likely to be a bottleneck for the H200 relative to Blackwells, as the H200 has a superior ratio of memory to processing performance to Blackwells. Therefore, we do not further consider memory storage in calculating memory-related price-performance comparisons between Blackwell chips and the H200, and instead focus on memory bandwidth price-performance comparisons.

-

Recent attempts to smuggle H200 and H100 chips into China have been met with federal criminal prosecutions,.

-

As we discussed in our report on B30As, the chip achieves roughly half the performance of the B300 at roughly half the price, making both chips roughly equally price-performant.

-

This was not a problem in our earlier report on Blackwells, since the main comparisons we drew were between B300s and B30As, both of which support native FP4.

-

While the H200 cannot perform mathematical calculations natively in FP4, it can work with model weights represented in FP4, and then conduct math in FP8. This yields much of FP4’s performance gains for inference, as the main bottleneck in inference is memory bandwidth, rather than processing power. Representing weights in FP4 halves the required memory bandwidth.

-

(200,000 Hoppers * 1,979 FP8 FLOP/s) / (200,000 Hoppers * 1,979 FP8 FLOP/s + 30,000 GB200s * 5,000 FP8) * 100 = 72.5%. See Appendix 3 for an explanation on why we use FP8 FLOP/s as our main performance metric.

-

See Appendix 4 for a breakdown of the installed base estimate.

-

See our recent report on Blackwell chips for IFP’s estimates of logic die production and HBM production in the US and China, further underscoring China’s severe AI chip production bottlenecks. The continuity of these bottlenecks is conditional on the US and allies maintaining and strengthening China-wide export controls on key semiconductor manufacturing equipment like extreme ultraviolet (EUV) and deep ultraviolet (DUV) immersion photolithography tools, as well as deposition, etch, process control, and other tools. See our Blackwell report for policy options for strengthening SME and HBM export controls.

-

Even if China is able to create artificial demand for Huawei in state-backed sectors or critical infrastructure to absorb Huawei’s limited chip supply, one could argue that those government or critical infrastructure users will be less expert than Chinese frontier AI developers like DeepSeek at contributing to upgrading Huawei’s software stack. In theory, a complete US AI chip ban could incentivize the CCP to redirect Huawei chips to DeepSeek and not less-expert users in order to have more expert labs upgrade Huawei’s software stack. This scenario is plausible as the CCP has already made DeepSeek work with Huawei, even causing DeepSeek to fail to complete a training run despite DeepSeek owning advanced NVIDIA Hopper chips (e.g. the H800) and cloud access to even more advanced Blackwell chips. On the other hand, this evidence suggests that export controls are past the point of no return: DeepSeek and other Chinese frontier AI companies will, voluntarily or by force, support Huawei’s software development. More importantly, even if Chinese AI labs help Huawei develop its software stack, it will be of little use if Huawei cannot scale supply due to US and allied export controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment.

-

Hopper and Ascends both use 8-bit as their lowest number formats, allowing a fairly straightforward like-to-like processing power comparison.

-

As opposed to the 20% price premium we previously calculated for a B30A cluster.

-

In our B30A report, we assumed that US exporters and China would subsidize sales to make up for the extra 20% cost of a B30A cluster relative to a B300 cluster for achieving the same aggregate processing performance. This was based on strategic value US chip companies place in keeping a foothold in the China market (evidenced by NVIDIA’s reductions in margins per wafer when selling the China-specific H20) and the strategic value China would place on acquiring cutting-edge Blackwell technology (similar to subsidies for other strategic sectors, such as electric vehicles, for which the Chinese government provided $45 billion in subsidies in 2023). Here, we apply the Blackwell report’s conservative scenario subsidies to each of the H200 scenarios, assuming lower Chinese willingness to subsidize purchases of less price-performant chips. This subsidy is no longer sufficient to close the cost gap in any of the H200 scenarios.

-

H200 chips use the same high-bandwidth memory components as Blackwell chips (HBM3e), similar chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS) technology, and logic dies at a similar process node (4N vs. the Blackwells’ 4NP). This means that ramping up H200 chip production would crowd out Blackwell chip production for the US and allied or neutral countries for as long as there are supply constraints of HBM3e, CoWoS, or logic die manufacturing capacity. H100 and H20 chips could similarly crowd out Blackwell production, although their memory technology is less advanced (HBM3). That said, it’s possible the “H20E,” an updated version of NVIDIA’s original H20, may use the more advanced HBM3e stacks. Crucially, transferring manufacturing capacity from Blackwells to Hoppers results in a reduction in globally installed compute, given that a Blackwell wafer generates more compute than a Hopper wafer, and likely also greater margin per wafer. As a result, we assess it is less likely than in the B30A case that US chip companies would go to extremes in allocating scarce, supply limited wafer capacity to Hoppers in favor of Blackwells, though they may still do so to a partial degree to maintain a foothold in the Chinese market.

-

We model all 2026-produced US compute produced by NVIDIA (which is 63 percent of all US production) to be capable of supporting FP4, as these chips will be exclusively Blackwell chips and future Rubin chips if released on time in late 2026. We also model an additional 7 percent of US compute, namely Google TPUs, as supporting 4-bit computation. Google TPUs represent roughly 13 percent of US production (based on CoWoS packaging shares to Broadcom, which co-designs TPUs with Google). However, TPUs support INT4, which is useful for inference but not training. Therefore, we count roughly half of TPU compute as useful for supporting 4-bit computation, assuming a roughly 50/50 split between training and inference. We assume that other US vendors either do not support 4-bit computation or produce small enough chip volumes that their contributions can be ignored for simplicity.

-

Our estimates rely on an H200 training cluster’s 20-70% price performance of a B300 training cluster, but for simplicity do not incorporate inference price-performance comparisons between H200 and B300 clusters. However, doing so would not fundamentally alter the result. As noted in the summary, this report finds that a B300 achieves 1-5x the price performance of the H200 in typical inference tasks, depending on workload. Additionally, half or more of AI compute is devoted to training.

-

The workload requires various types of parallelism, including tensor parallelism and expert parallelism, across a large number of chips, i.e. splitting aspects of the AI model across these chips to process them in parallel.

-

We calculate this based on three cliffs in utilization as clusters scale beyond 8 chips (where throughput dropping from 24 to 17 tokens per second), beyond 16 chips (where throughput drops from 11.5 to 8.5 tokens per second), and beyond 32 chips (where throughput drops from 5.5 to 3 tokens per second). These cliffs cause utilization to achieve only 29% ((17/24)*(8.5/11.5)*(3/5.5)) of utilization with no cliffs, or a 3.5x loss.

-

In conversation with IFP, industry experts said that some penalty may appear for the largest pretraining clusters (well over 100,000 AI chips). However, in general, pretraining requires lower NVLink bandwidth and parallelism schemes be can designed to avoid networking constraints even for large clusters.

-

NVIDIA’s benchmarking found a 4-5x Blackwell advantage relative to the H200 for a dense model (Llama 3.3 70B) and a small MoE (gpt-oss 120B), rather than a 30x advantage. This means that the remaining 4-5x advantage would mostly disappear after adjusting for price-performance, as separately discussed in this appendix. (Both of these models cannot run on Blackwell’s FP4 engine, so no further adjustment is necessary to account for Blackwell’s FP4 capability.)

-

See slide 22 of an NVIDIA presentation.

-

Fewer bits means fewer resources need to be used to store data, move it around, and perform calculations. This is because the circuits used to add or multiply lower-bit numbers are simpler and can be packed more densely, and because lower-bit numbers require both less memory to store and less bandwidth to move around.

-

TPP = 2 * dense MacTOPS * bit length of the operation (e.g., FP4, FP8, INT8), aggregated over all processing units on the integrated circuit. Typically, dense MacTOPS is half of a chip company’s reported dense performance (e.g., in FLOP/s or TOP/s) at a given bit length. Therefore, another way to calculate TPP is to take the reported dense performance at a given bit length and calculate TPP = dense performance * bit length. This calculation should be repeated for all bit length operations the chip supports, and TPP will be the maximum value these repeated calculations yield. That is, TPP = maxx([dense performance at bit length X * bit length X).

-

The cited analysis was published on May 28, 2025, so it is likely that the 2025 number for FP4 is higher than shown here. We include this chart to show the broader point that lower number formats have historically taken time to be widely adopted in AI training.

-

In training, the entire input dataset is generally already available, and that dataset can be split up into large batches and parallelized over many accelerators. In inference, input data arrives over time in a harder-to-predict fashion, meaning that each accelerator works with much smaller batches of data in order to return outputs to users within a reasonable time. Because generating each token requires reading both the model weights and the accumulated key-value cache from previous tokens in the sequence, memory bandwidth becomes the primary bottleneck rather than raw processing speed. Small batch sizes exacerbate this: the chip must move large amounts of data through memory to perform relatively few arithmetic operations, leaving compute capacity underutilized while waiting on memory transfers.

-

Algorithmic innovations might further increase utilization to unlock Blackwell FP4 acceleration. DeepSeek recently pioneered multi-head latent attention (MLA), a technique that reduces memory usage and therefore unlocks greater FLOP/s utilization, potentially enabling enough utilization to leverage Blackwell’s FP4 extra FLOP/s. However, DeepSeek recently shifted to DeepSeek sparse attention (DSA), a sparse variant of MLA, which reduces both memory and FLOP/s usage, putting the algorithmic frontier at a FLOP/s vs. memory bandwidth ratio that likely makes it difficult to unlock Blackwell FP4 acceleration.

-

TFLOP/s average across B300s (5,000), B200s (5,000), and B100s (3,500).