Permitting reform has a problem. Why would members of the party out of power vote for a permitting deal if the President can cancel the projects they care about after the deal passes?

To pass bipartisan permitting reform, Congressional policymakers need to figure out how to create permitting certainty — a state of affairs that prevents politicians from abusing permitting processes against disfavored projects. Finding a solution is now mandatory: Senators Whitehouse and Heinrich, lead Democratic negotiators, have paused permitting reform negotiations specifically because the administration has abused the permitting system to block offshore wind projects.1 Fortunately, a new bill called the FREEDOM Act offers a compelling solution. Sponsored by Representatives Josh Harder (D-CA), Mike Lawler (R-NY), Adam Gray (D-CA), Don Bacon (R-IL), Chuck Edwards (R-NC), and Kristen McDonald Rivet (D-MI), the FREEDOM Act creates real certainty for developers by establishing clear timelines for issuing permits, stopping administrations from revoking permits for fully approved projects, and enforcing these mechanisms with a process of judicial review and clear remedies.

Permitting certainty is key to making the political logic of bipartisan permitting reform work. In order to vote for a deal, policymakers on both sides need to feel confident that projects they support will benefit from broader reforms. But that’s not the main reason permitting certainty is so important, or the main reason it should be embraced by politicians from both parties. By protecting projects from capricious attacks, permitting certainty will increase investment in energy production generally, reducing regulatory risk and letting companies plan long-term projects. If lawmakers are serious about bringing down costs for regular Americans, they will struggle to do better than protecting new energy production.

This paper explains first how executive abuse of permitting happens, detailing the different avenues for delay throughout the process of getting a project approved. Then, we illustrate how the FREEDOM Act proposes to solve those challenges at each stage.

The problem

One reason building infrastructure in America is so difficult and expensive is the numerous federal permits and approvals required to build. These permitting processes entail compliance with a host of complex procedural laws. Even when the government processes these permits in good faith, the process can be hamstrung by litigation, where project opponents have many opportunities to slow and even kill projects for minor procedural mistakes.

But when the government does not act in good faith, the permitting process can be weaponized to intentionally sabotage disfavored projects — or even entire industries. This has happened over many administrations, but has ramped up to an unprecedented degree in the current administration.

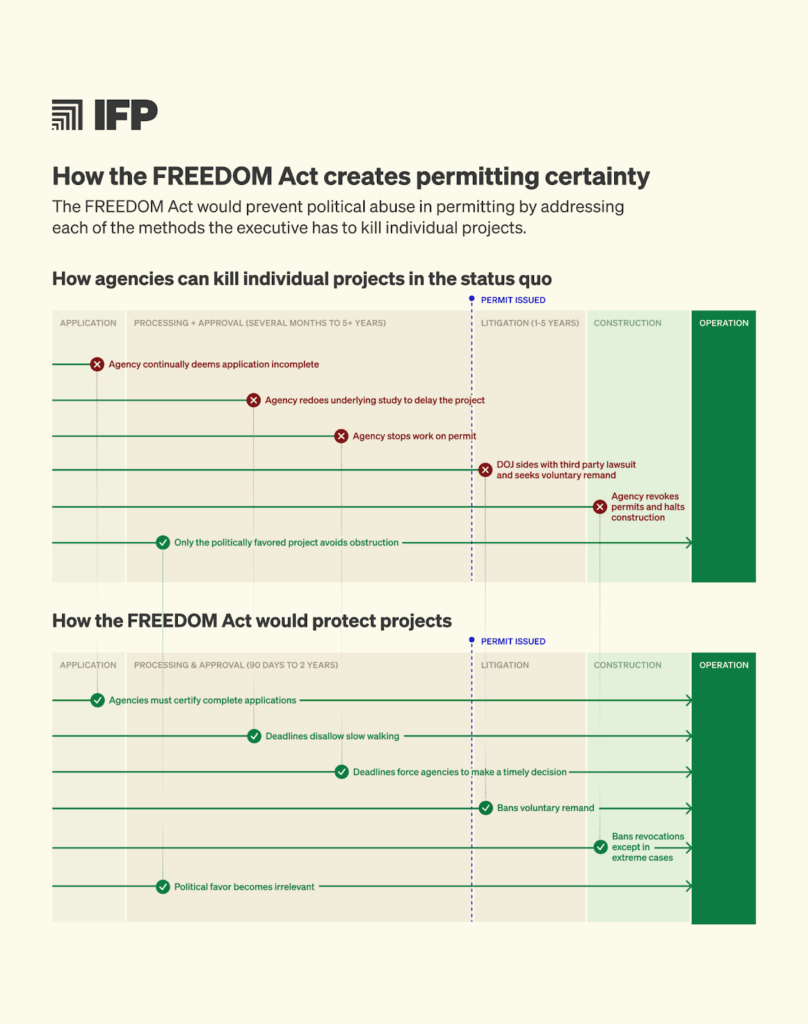

There are numerous stages at which an administration that is dedicated to stopping a given project can intervene. We identify five main stages of the permitting process: pre-application, application, processing & approval, litigation, and construction. Each phase offers different avenues for political officials to delay, deny, or abuse the permitting process in order to harm disfavored projects. Abuse at any single phase is often enough to kill or delay a project indefinitely. The chart below demonstrates the gauntlet of risks a project faces from political abuse.

Each stage has its own challenges. Reforms need to enable “permitting certainty” to ensure developers are treated fairly, permits are evaluated on the merits, and projects are not halted after they have been approved.

But creating permitting certainty is difficult. American permitting processes were created to prevent environmental harm, not to guard against political abuse. Our permitting laws assume that the government will attempt to complete required regulatory approvals in a timely manner. The enforcement mechanisms in these laws reflect that assumption. For example, if the government does not comply with laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act, or the National Historic Preservation Act when permitting a project, then courts can set aside the permit and halt construction.2 If companies violate the Clean Air Act or Clean Water Act’s pollution standards, regulators and courts can impose fines and force the company to repair the damage.3 But, on the other hand, if the government delays or uses pretextual reasons to block a disfavored project, there is little the developer or courts can do. America’s environmental laws were simply not built for a government that intentionally slows or denies projects. This challenge is reflected in each of the phases of the permitting process.

Pre Application

The pre-application phase is the time before a project begins the federal permitting process. While this phase is not a formal permitting stage, it can still be abused to cut off disfavored projects. For example, an administration might cut off or reduce eligible leasing areas, or choose to only list areas that are infeasible for development. In fact, the use of leasing policy to reduce development from disfavored industries has been used by Presidents from both parties:

Obama:

- In 2012, the administration withdrew 1 million acres of eligible uranium mining leasing areas.4 From 2014-2016, the administration canceled onshore oil & gas lease sales in parts of Montana and Colorado.5

- In 2016, the Obama administration paused all coal leases in order to begin a new Programmatic EIS for federal coal programs.6

- From 2014 to 2016, the Obama administration also withdrew significant portions of the Arctic and Atlantic from offshore oil drilling eligibility, as well as designating the Bering Sea as a conservation area in order to block offshore oil drilling.7

Trump I:

- In 2020, the Trump administration disrupted the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) in order to delay and limit eligibility for renewables leases.8

Biden:

- In 2021, Biden paused the issuance of new oil & gas leases on federal lands and offshore waters.9

- In 2025, the Biden administration intentionally structured the 2025 Arctic lease sale to be as unattractive as possible for oil & gas developers.10

- The administration also delayed the required five-year plan for offshore drilling lease sales and then only scheduled three offshore lease sales and only in the Gulf of Mexico.11

- The Biden administration also attempted to remove 6 million acres from the Gulf lease sale at the last minute and impose speed limits on vessels servicing offshore rigs.12

- In January 2025, Biden withdrew all offshore leasing areas for oil & gas in the Atlantic and Pacific, and most of the area from the Gulf and Arctic leasing areas.13

Trump II:

- In January 2025, the administration canceled all offshore wind leasing areas under OCSLA while, at the same time, significantly expanding offshore oil & gas leasing.14 In December 2025, it used the suspension of leases to retroactively cancel existing offshore wind projects.15

Application

While often overlooked as a minor procedural step, the application phase can and has been used to delay and block permits. To receive a federal permit, project sponsors have to apply and submit a series of technical documents and other materials. Then the agency needs to receive the materials, review them, and determine if the sponsor’s application is complete (or if they need to submit further information). Finally, if the agency determines the application is complete, it must initiate review under the relevant permits and authorizations in order to move to the Processing & Approval phase.

But none of these steps are automatic. There’s little that project sponsors or courts can do to force an administration to accept a complete application in a timely manner. While existing law does empower courts to review “unreasonable delays,” the cost of litigating can be prohibitive, and case law requires courts to be deferential to agencies — often allowing years-long delays.16

For example, as a result of Executive Order 14315 stating that agencies should take actions to prevent wind and solar permits, the Federal Aviation Administration started refusing to answer wind developer’s requests for routine permits needed to certify compliance with aviation safety standards.17 Without a way to apply for this mandatory permit, developers cannot move the process forward. The application phase can also be used by agencies as a negotiating tactic to force the applicant into terms the agency would prefer.18

Processing & Approval

The main stage of federal permitting is Processing & Approval. Federal agencies review the particulars of a project, conduct environmental analysis, and approve or deny projects for federal permits. Permitting at this stage is especially vulnerable: even without interference, preparing environmental permits is a genuinely complex task. Permits require executing complicated environmental studies, understanding disparate effects on complex ecological systems, and coordinating between federal agencies, the project sponsor, states, tribes, and local communities. Finalizing the permit also requires significant coordination between legal advisors and different parts of government. Each of these tasks must be done well for a permit to be approved; a single error can delay or halt the entire project. If review is imperfect, even a project favored by the government can fail in litigation later. The complexity of preparing permits makes it easy for political officials to intentionally delay disfavored projects and then make a pretextual excuse for the delays in public.

Political officials have several options to slow disfavored projects. The most common delay tactic is for political officials to insist that a disfavored project needs to do more review, or pause while the agency redoes underlying studies. Officials can also fire or reassign important technical staff to stall review. Agencies can insist on burdensome mitigations requirements for disfavored projects, or force sponsors to redo scoping or submit lengthy alternative plans.19 If officials don’t care about creating an excuse for delays, agencies can simply refuse to answer emails and sit on a permit indefinitely. Worst of all, agencies can set an official policy to disadvantage disfavored industries.

Recent administrations have implemented all of these stalling techniques at various points:

Obama:

- The Obama administration chose to redo a programmatic review for coal leasing.20

- It directed the Army Corps of Engineers to conduct a more comprehensive environmental review of the Dakota Access Pipeline (an EIS).21

- The administration also delayed the Keystone XL Pipeline for years, including denying but allowing the company to reapply in order to circumvent a Congressionally set deadline, only to then deny the Presidential Permit for border crossing in 2015.22

Trump I:

- The first Trump administration delayed Vineyard Wind for multiple years on the basis that the project needed to do more “cumulative impacts” analysis — a portion of NEPA analysis that the administration removed from NEPA regulations in 2020 and again in 2025, and through agency guidance instructed agencies not to consider at all.23

- The administration also delayed the FHWA’s review of congestion pricing in New York City by refusing to tell the Metropolitan Transit Authority whether it needed to complete an Environmental Assessment (EA) or Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) under NEPA.24

Biden:

- The Biden administration slow-walked approving Public Interest Determinations for liquified natural gas terminals, extending what had been a 90-day approval under Obama and a 60-day approval under Trump, to ~300-500 days.25 Then, in 2024, the Biden administration issued a full pause on review of export terminals, arguing that the underlying studies needed to be redone before any further consideration could move forward.26

Trump II:

- The second Trump administration formalized intentional delay as policy. In July 2025, the Department of the Interior issued a memo requiring the secretary’s office to personally sign off on any permitting authorization for renewables projects, including small and routine authorizations like approving access roads.27 The policy not only offers a clear directive for political appointees to interfere, it creates a lengthy and painful internal process of reviewing renewable projects. The results seem to have immediately frozen reviews of renewables. Multiple developers have said they haven’t heard anything from the Bureau of Land Management about processing timelines.28

Litigation

Once a project is fully approved, it can be challenged in court by third parties. Third parties and courts can delay projects in litigation, but litigation also provides the government an opportunity to side with project opponents. The federal government is the party responsible for defending the permits that project sponsors rely on. If the government switches sides — from defending its own decision making on the permit to agreeing with project opponents that the decisionmaking was flawed — it can petition for “voluntary remand” and ask a court to overturn the government’s own permit, sending a review back to the Processing & Approval stage. Courts almost always grant voluntary remand, even if the project sponsor dissents. This technique has also been used by multiple administrations:

Obama:

- The EPA filed for voluntary remand of the Desert Rock coal plant on the Arizona-New Mexico border, over the objection of the Desert Rock Energy Company.29

Biden:

- The Biden administration used voluntary remand to halt the Cadiz Water Pipeline in California, again despite the project sponsor’s opposition.30

Trump II:

- The Trump administration has used voluntary remand against offshore wind en masse, asking courts to set aside the permits for Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, SouthCoast Wind, New England Wind Farm, and Maryland Offshore Wind, all over the objections of the project sponsors.

Construction

Political abuse can even harm projects that are permitted and have already begun — or even completed — construction. Agencies can revoke permits and issue stop-work orders by claiming the permits they issued are inadequate. Agencies can do this even if they previously believed permits were adequate. Case law is clear that agencies have authority to reconsider their prior decisions;31 they do not need to demonstrate a better justification for their new decision, it just cannot be “arbitrary and capricious.”32 Revoking permits for fully approved projects has been used more frequently in recent years.

Obama:

- The Obama administration revoked a dredge and fill permit under section 404 of the Clean Water Act for Spruce No. 1 coal mine in West Virginia.33

Biden:

- The Biden administration revoked a Presidential border crossing permit for the Keystone XL Pipeline and blocked Twin Metals copper mine by revoking the project’s leasing renewals.34

Trump II:

- The second Trump administration has used stop work orders to delay Revolution Wind.

- The administration also used a stop work order against Empire Wind.

- In December 2025, the Trump administration moved to suspend all ongoing offshore wind leases, effectively revoking approval for all approved offshore wind projects.35

Existing laws are ill-equipped to handle permitting abuse.36 Under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), plaintiffs can allege that agencies have unreasonably delayed issuing a permit.37 However, in practice these claims are almost never successful. Moreover, if a claim were to succeed, there is little that courts can do to force agencies to take action.38

Getting rid of abuse will require fixing each of the problems laid out above. It is not enough to fix a single issue if the other veto points remain. For example, if Congress were simply to forbid revoking permits, agencies could still block disfavored projects by petitioning for voluntary remand, or by delaying Processing & Approval indefinitely. Or, if Congress sets deadlines for Processing & Approval, agencies can deny applications minimal explanation, or cut off projects by removing eligible leasing areas.

Finally, no reform will matter without a clear and effective enforcement mechanism. For example, if Congress banned permitting revocations but did not create any new judicial remedies, there would be nothing to prevent a bad faith administration from borrowing from the litigation doom loop to repeatedly issue revocations that halt construction and exact months of delay in court while project sponsors fight each successive order. Similarly, setting deadlines for agencies to issue permits won’t accomplish anything if there is no way to force agencies to issue permits once the deadline is missed. A slap on the wrist from courts isn’t enough. Congress needs to set penalties that are painful enough to incentivize agencies to issue permits on time and in accordance with the law.

The solution: The FREEDOM Act

Creating permitting certainty requires addressing abuse in each of the five phases: pre-application, application, processing & approval, litigation, and construction. As long as one veto point remains, bad-faith actors will be able to block projects. Moreover, reforms need to be enforceable and backed by robust legal remedies: courts need new authority to compel action, compensate sponsors, and thereby strongly disincentivize federal agencies from breaking the new rules. Finally, accessing the new remedies must be easy and efficient; project sponsors need to be able to easily enforce deadlines and overturn illegal delays without lengthy litigation.

Fortunately, a new bipartisan bill offers a solution. The FREEDOM Act tackles permitting certainty by setting universal timelines on all federal permits and authorizations. It also prevents action against projects with approved permits by banning voluntary remand and limiting revocations to extreme cases. Most importantly, FREEDOM backs all of these measures with new remedies including: fees paid to the project sponsor for missed deadlines, a court-appointed contractor to finish environmental review, and damages suffered as a result of illegal stop work orders. The solution is technology neutral and designed to benefit certainty for developers by preventing abuse and the whiplash of different treatment under different administrations.

How the FREEDOM ACT works

The FREEDOM Act tackles permitting certainty by working backwards from the need to create an effective judicial review process with low costs and high benefits. Political abuse cannot be policed by the executive branch that is doing the abuse, so enforcement must be through a private right of action that allows affected project sponsors to hold the government accountable. Subtitle D of the FREEDOM Act eliminates the complexity of claiming unreasonable delay under the APA by specifying that the only condition needed to establish unreasonable delay is whether the agency missed the reasonable deadlines that the bill sets on all federal authorizations. FREEDOM sets deadlines based on the difficulty of the review: 90 days for routine permits, one year for complex permits, and two years for complex permits that require an EIS. This prevents risk aversion from companies who might otherwise avoid legal action; if the deadline has been missed, the agency is guilty of unreasonably delaying the authorization, and the sponsor is eligible for remedies.

To ensure courts have tools to enforce the new standards, FREEDOM introduces new remedies for courts to apply. First, FREEDOM creates monetary remedies for missed deadlines. If agencies miss the new deadlines, they owe the project sponsor fees — $1,000 to $100,000, depending on the size of the project — for each day of delay. These fees serve to disincentivize the government from abusing the permitting process and as compensation to companies that have been unfairly delayed.

Second, if an agency issues a stop work order or revokes a permit and a court overturns the action, the agency must pay the sponsor for any damages that resulted from the delay. For example, Revolution Wind and Empire Wind would have been entitled to $60 million and $50 million for their respective delays.39 And, to ensure damages function as a disincentive to federal agencies, FREEDOM would require that all monetary damages are paid out of the relevant agency’s appropriations.40

Finally, for cases of missed deadlines, FREEDOM would create a novel remedy and direct courts to appoint a contractor to complete any outstanding review. This gives project sponsors an option if agencies refuse to complete required materials.41

How FREEDOM addresses the phases of permitting

Pre-application: FREEDOM is written to focus narrowly on permitting reforms rather than leasing policy, and thus does not address the pre-application phase. However, as part of permitting discussions, policymakers should consider provisions to ensure both fossil and renewable leases can be processed regularly and effectively.42

Application: The FREEDOM Act sets an airtight timeline for certifying applications. FREEDOM sets clear expectations for what applications must contain, including a statement of purpose, a concise description, and a list of required environmental reviews. FREEDOM gives the receiving agency 30 days to determine if the application is complete or incomplete. If the agency does neither the application is deemed complete and the timeline for review starts. If agencies issue a deficiency notice, sponsors have 30 days to resubmit their application. If project sponsors need more time, they can request an extension up to a total of 90 days. Finally, FREEDOM requires that, within 30 days of deeming an application complete, the responsible federal agency must notify the project sponsor with a list of all applicable authorizations and whether the permit is routine or complex. All of these deadlines and requirements can be reviewed by a court for potential delay and violations.

Processing & Approval: Subtitle D of the FREEDOM Act prevents abuse during the processing of permits by setting universal deadlines on all federal authorizations required to approve a project. Timelines are set by the difficulty of a project. Routine authorizations are all non-complex projects. Complex authorizations are for projects that require an EA or EIS under NEPA, or one of several other lengthy permitting authorizations.43 Agencies are given 90 days to complete all authorizations for routine projects, one year for complex projects, and two years if a complex project requires an EIS.44

The act specifies that missing a deadline is sufficient grounds for a sponsor to take an agency to court and seek remedies. Claims over missed deadlines would then be adjudicated and result in fines paid from the agency to the project sponsor — from $1,000 a day for small projects to $100,000 per day for large projects. Courts would also be allowed to nominate a contractor to complete any outstanding review and analysis needed to complete the authorization. The government would pay for the contractor’s service, and courts would order the agency to finalize the resulting review.

In case the sponsor needs even greater protection from permitting risk, FREEDOM creates an optional insurance fund called the De-risking Compensation Program. The program would allow the sponsor to buy in at 1.5% of the project’s cost and be eligible for damages in case of mistreatment, defined as a violation of the process described in FREEDOM — e.g. unreasonable delay for missed deadlines, illegal stop work orders, etc. The sponsors would be eligible for damages paid from the insurance fund until the funds run out.

Litigation: Subtitle F of the FREEDOM Act forbids the government from petitioning for voluntary remand — i.e., sabotaging a project by agreeing with third party lawsuits and asking a court to set aside a permit for reconsideration — unless the project sponsor consents. This cuts off abuse while allowing voluntary remand when the project sponsor consents.45

Construction: The FREEDOM Act would restrict revocations and any other form of cancellation or delay against fully approved projects. Subtitle F of FREEDOM would require an agency seeking to revoke a permit to demonstrate either that a court has ordered the action, or that there is both a clear, immediate, and substantiated harm and no alternative solution that would allow construction to continue while the harm is repaired.46 If a federal agency revokes a permit or stops work and a court overturns the order, the agency must pay sponsors for any damages suffered as a result of the delay.

Conclusion

The FREEDOM Act is built to work even if agencies bend or break the rules. Each limit on abuse is written to be easy to resolve in court and backed by remedies that disincentivize bad behavior. Sponsor-led enforcement ensures no project sponsor will be left without recourse. And the remedies are built to be painful for federal agencies — fees and damages are paid out of the responsible agency’s general fund, meaning the cost will hamper their ability to pay for other priorities that political officials care about. All of these features are written to give certainty to developers and ensure investment is not chilled and development is not blocked. The bill’s goal is not to create continual litigation, but rather to set a policy structure where abuse is extremely rare, because the consequences provide a clear disincentive.

The FREEDOM Act is an emphatic demonstration that it is possible for a bill to create permitting certainty, even if an administration tries to bend or even break the rules. The bill offers certainty to renewables in the short term, but also to fossil and other projects that might be mistreated in the long term under a Democratic president. The bill is a compelling answer on permitting certainty that should spur further negotiation on a broader permitting reform package.

-

Seigel, J., & Tamborrino, K. (2025, December). “Senate Democrats cut off permitting talks after Trump’s newest ‘assault’ on wind.” Politico.

-

Congressional Research Service. “National Environmental Policy Act: Judicial Review and Remedies.” Congress.gov. June 2025. See the “Remedies in NEPA Litigation” section for discussion.

-

For the Clean Air Act, see U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “Air Enforcement Policy, Guidance and Publications.” epa.gov. Updated December 2025. For the Clean Water Act, see Code of Federal Regulations. “33 CFR Part 326 — Enforcement.” ecfr.gov. December 2025.

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Record of Decision: Northern Arizona Withdrawal, Mohave and Coconino Counties.” webapps.usgs.gov. January 2012.

-

Institute for Energy Research. “Obama Cancels Lease Sales and Withdraws Federal Lands from Oil and Gas Development.” eir.com. December 2016.

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Order No. 3338: Discretionary Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement to Modernize the Federal Coal Program.” blm.gov. January 2016. See Section 5.

-

Obama, Barack. “Presidential Memorandum — Withdrawal of Certain Portions of the United States Arctic Outer Continental Shelf from Mineral Leasing.” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. December 2016. Also see Obama, Barack. “Executive Order — Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience.” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. December 2016.

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Bureau of Land Management Announces Draft Environmental Impact Statement for Desert Plan Amendment.” BLM.gov. January 2021.

-

Biden, J. R., Jr. “Executive Order on Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad.” bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov. January 2021. See Section 208.

-

Congressional Research Service. “Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Status of Oil and Gas Program.” Congress.gov. July 2025. See the section titled “January 2025 lease sale.”

-

Congressional Research Service. “Five-Year Offshore Oil and Gas Leasing Program: Status and Issues in Brief.” everyCRSreport.com. December 2025.

-

Reuters. “Oil companies sue U.S. over Gulf auction changes meant to protect whale.” Reuters.com. August 2023. Also see Louisiana v. Haaland, No. 2:23-cv-01157 (W.D. La. Sept. 21, 2023).

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “President Biden Takes Action to Protect America’s Coastlines from Future Oil and Gas Leasing.” doi.gov. January 2025.

-

Trump, D. J. “Temporary Withdrawal of All Areas on the Outer Continental Shelf from Offshore Wind Leasing and Review of the Federal Government’s Leasing and Permitting Practices for Wind Projects.” whitehouse.gov. January 2025.

-

Nilsen, I. “Trump suspends all large offshore wind farms under construction, threatening thousands of jobs and cheaper energy.” CNN.com. December 2025.

-

See generally, Congressional Research Service. “Administrative Agencies and Claims of Unreasonable Delay: Analysis of Court Treatment.” everyCRSreport.com. March 2013.

-

Holzman, J. “Trump’s Total War on Wind Power.” Heatmap.com. August 2025. Also see Trump, D. J. “Executive Order: Distorting Subsidies for Unreliable, Foreign Controlled Energy Sources.” whitehouse.gov. July 2025.

-

Energy and Wildlife Action Coalition. “Comments Regarding the June 9, 2025 Notice Requesting Public Input on Endangered Species Act Section 10(a) Program Implementation.” energyandwildlife.org. June 2025. EWAC states that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service either refuses to acknowledge an application is complete or rejects the application as incomplete as a negotiation tactic.

-

Northern Dynasty Minerals Ltd. “Northern Dynasty: Pebble Partnership to challenge U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ finding that Compensatory Mitigation Plan for Alaska’s Pebble Project is non-compliant.” northerndynastyminerals.com. December 2020.

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Order No. 3338: Discretionary Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement to Modernize the Federal Coal Program.” BLM.gov. January 2016. See Section 5.

-

For the coal leasing pause, see U.S. Department of the Interior. “Secretary Jewell Launches Comprehensive Review of Federal Coal Program.” doi.gov. January 2016. For the Dakota Access decision, see U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “Notice of Intent to Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement for the Dakota Access Pipeline Crossing of Lake Oahe, North Dakota.” FederalRegister.gov. January 2017.

-

Obama, B. “Statement by the President on the Keystone XL Pipeline.” obamawhitehouse.archives.gov. November 2015.

-

Young, Colin A. “Federal Review Will Further Delay Vineyard Wind.” wbur.org. August 2019. For the second Trump administration's position on cumulative impacts, see Council on Environmental Quality. “Memorandum for Heads of Federal Departments and Agencies.” ceq.doe.gov. February 2025.

-

McNulty, M., et al. “Congestion Pricing Another Victim of Trump’s Vindictive Stance on Infrastructure.” rpa.org. September 2020. As soon as the Biden administration came in, they issued the ruling that New York City’s congestion pricing required an environmental assessment; see U.S. Federal Highway Administration. “FHWA Greenlights Environmental Assessment for New York City’s Proposed Congestion Pricing Plan.” highways.dot.gov. March 2021.

-

Curtis, W. “U.S. reviews of gas-export permits slow under Biden administration.” Reuters.com. October 2023.

-

U.S. Department of Energy. “DOE to Update Public Interest Analysis to Enhance National Security, Achieve Clean Energy Goals and Continue Support for Global Allies.” doe.com. January 2024.

-

U.S. Department of the Interior. “Departmental Review Procedures for Decisions, Actions, Consultations, and Other Undertakings Related to Wind and Solar Energy Facilities.” doi.gov. July 2025.

-

Groom, N. “Wind and solar power frozen out of Trump permitting push.” Reuters.com. July 2025.

-

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 9. “EPA Region 9’s Motion for Voluntary Remand, In re Desert Rock Energy Company, LLC.” biologicaldiversity.org. February 2009.

-

United States District Court for the Central District of California. “Defendants’ Notice of Motion for Voluntary Remand and Memorandum in Support.” biologicaldiversity.org. March 2021.

-

U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Ivy Sports Medicine, LLC v. Burwell. September 12, 2014.

-

U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. National Association of Home Builders v. Environmental Protection Agency. June 22, 2012.

-

Broder, J. M. “Agency Revokes Permit for Major Coal Mining Project.” NYTimes.com. January 2011.

-

Monsurud, A. “Interior Department revokes Minnesota mine leases.” CourthouseNews.com. January 2022.

-

Nilsen, Illa. “Trump suspends all large offshore wind farms under construction, threatening thousands of jobs and cheaper energy.” CNN.com. December 2025.

-

The Executive’s control of permitting is ultimately based on the Executive’s constitutional authority to take care that the law is executed.

-

Congressional Research Service. “Administrative Agencies and Claims of Unreasonable Delay: Analysis of Court Treatment.” everyCRSreport.com. March 2013. For example, in one circumstance, a court determined a delay of ten years on reaching a decision to be reasonable.

-

Courts can only order agencies to finalize review as expeditiously as possible, but these orders are vague and deadlines set by agencies are rarely effective.

-

For Revolution Wind, see Plumer, Brad and Friedman, Lisa. “Judge Says Work on Wind Farm Off Rhode Island Can Proceed, for Now.” NYTimes.com. September 2025. For Empire Wind, see Spring, Jake. “Trump officials allow massive New York offshore wind project to restart.” WashingtonPost.com. May 2025. For damages from recent cancellations, see Utility Dive. “Ørsted, Equinor challenge Trump administration stop work order.” UtilityDive.com. January 2026.

-

By forcing agencies to pay out of their appropriated funds rather than the judgment fund in the U.S. Treasury, the FREEDOM Act avoids principal-agent problems and incentivizes agencies to avoid paying out fees.

-

The court approved contractor would complete the remaining permitting materials, including any outstanding studies or analysis needed to bring the review into compliance with the relevant statutes. The contractor would then give the completed review back to the agency to officially approve, since the law requires the agency itself make the determination and decision. This structure gives courts the ability to compel action because it removes the agency’s excuse of needing more time to complete lengthy studies.

-

Fortunately, the main avenue for preventing projects at the pre-application stage is federal leasing policy, and existing bills already chart a solution. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) made successful oil and gas lease sales a precondition for allowing wind and solar leases. Policymakers should first expand on this idea and tie fossil and renewables leasing together by requiring the two types to alternate — once one industry is offered a lease sale, it cannot receive another lease sale until the other industry is offered one first. Congress should specify that if this requirement is violated then courts can overturn or pause leasing for the other industry type. Second, to guard against hostile sales where an administration only offers unusable land to disfavored industries, Congress should require that lease sales include at least 50% of industry nominated parcels, up to a cap of half the total required acreage. This would ensure that lease sales include desirable land, but maintain some discretion for federal agencies to omit potentially sensitive lands. While these reforms are not included in the FREEDOM Act, Congress should consider this reform, or similar reforms, to ensure permitting certainty is comprehensively addressed.

-

The full list of triggers for the definition of a complex authorization include authorizations under: the National Historic Preservation Act, the Endangered Species Act, a new right-of-way or lease of federal land, the Clean Water Act, the Federal Power Act, the Natural Gas Act, or the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. See Subtitle D, SEC 12301(d)(2), Definitions of the FREEDOM Act.

-

This complies with the Fiscal Responsibility Act’s NEPA timelines that set one year for environmental assessments and two years for environmental impact statements.

-

This is important because, in some cases, the government and sponsor will realize an error in their authorizations and move to correct it as soon as possible rather than continuing through lengthy litigation.

-

For example, if an agency issued a stop work order based on national security, the sponsor would be able to sue and force the agency to justify why the national security concern is clear, immediate in time, and why there was nothing else the agency could have done to alleviate the concern. For example, the December 2025 suspension of offshore wind leases is based on the claim that offshore wind projects create radar clutter. This reasoning would be hard to sustain if the Department of the Interior had to explain why there was nothing else it could have done to repair this issue short of halting construction of fully approved projects.