Summary

- This is a Request for Proposals (RFP) to contribute to the next iteration of The Launch Sequence: an initiative to develop projects that prepare the world for advanced AI.

- You can use this link to submit a proposal. Your proposal should be a short (200–400 words) pitch for a project that will accelerate science, strengthen security, or adapt institutions in anticipation of widespread advanced AI.1

- You should submit a proposal if you have a good idea, even if you don’t expect to be the person actually leading or working on the resulting project. However, we’re especially excited about proposals from people who plan to lead projects themselves.

- If your proposal is selected, we’ll work closely with you to develop the idea into a concrete project plan, publish your plan, connect you with philanthropic funders, and help you headhunt for a project lead or co-lead.

- On top of support from the IFP team, you’ll also have the support of our advisory panel for The Launch Sequence: Tom Kalil (CEO, Renaissance Philanthropy), Matt Clifford (Co-founder and Chair, Entrepreneurs First, and Chair of ARIA), and Wojciech Zaremba (Co-Founder, OpenAI).

- Authors of published proposals will receive a $10,000 honorarium. We are also offering $1,000 bounties for successful referrals and for new ideas that we end up publishing.2

- This is a rolling RFP with no submission deadline, but we will prioritize early submissions and start reviewing immediately.

About The Launch Sequence

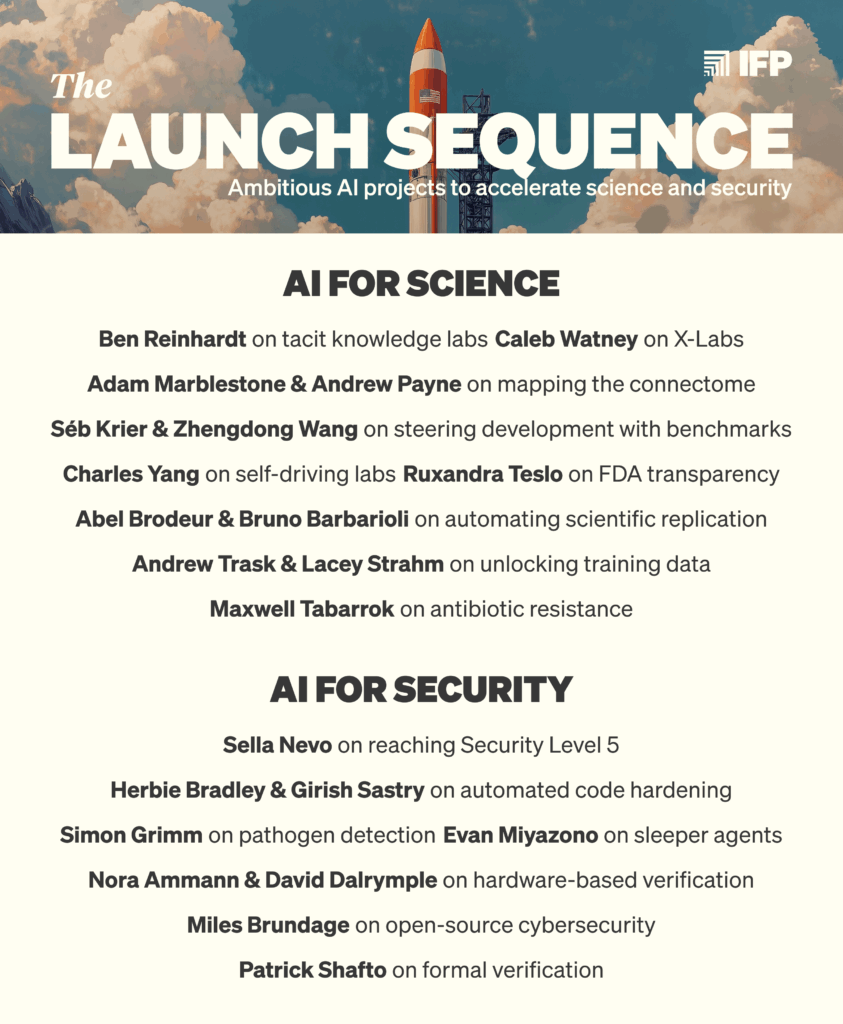

In 2025, IFP published The Launch Sequence, a set of proposals aimed at answering one question: what does America need to build, which will not be built fast enough by default, to prepare for a future with advanced AI?

As we explained in the foreword to the collection, Preparing for Launch, we need to solve two broad problems:

- The benefits of AI progress may not come quickly enough.3

- AI progress may bring risks that industry is poorly incentivized to solve.4

We invited some of the sharpest thinkers, engineers, and scientists thinking about these topics to write 16 concrete proposals to address these problems.

Since then, many of the proposals have gained real-world traction:5

- Caleb Watney’s X-Labs proposal inspired a new billion-dollar National Science Foundation program and a bipartisan bill

- A philanthropic fund based on Biotech’s Lost Archive was announced yesterday to purchase common technical documents (CTDs)6 from companies

- The Great Refactor’s author, Herbie Bradley, secured grants from IFP and other philanthropic funders to explore founding a nonprofit to eliminate memory safety vulnerabilities in open-source code & critical infrastructure

- A bill based on The Replication Engine is being drafted to be introduced in Congress

- Many proposal authors are continuing to build their solutions: Patrick Shafto is building tools to accelerate and formalize math at DARPA, Sella Nevo is working on SL5 at RAND, Simon Grimm is scaling metagenomic sequencing at the Nucleic Acid Observatory, Andrew Payne is making connectomics much cheaper at E11 Bio, Abel Brodeur and Bruno Barbarioli are building an AI replication engine at the Institute for Replication, and Andrew Trask and Lacey Strahm are pioneering Attribution-Based Control at OpenMined

What we are doing now

Major new funding is flowing into this space. The OpenAI Foundation committed $25 billion to AI resilience and curing diseases. The Chan-Zuckerberg Initiative is refocusing most of its philanthropic spending on AI projects to “cure all disease.” The White House launched the Genesis Mission, a “national effort to unleash a new age of AI‑accelerated innovation and discovery.” Philanthropies and government officials are asking us for more ideas about where this money should be directed.

This is a momentous opportunity, and how well these funds are spent will depend both on the quality of available ideas and on teams being ready to implement them.

That’s why The Launch Sequence is transitioning into a rolling effort to:

- Find promising ideas

- Vet these ideas with our advisors and expert network

- Develop concrete project plans, so they are as ready for funding and implementation as possible

- Matchmake funders and founders interested in the same ideas

The output of The Launch Sequence will be a collection of thoroughly vetted, detailed project plans for philanthropists to fund or for policymakers to implement.7

Our advisors

We’re excited to announce our official Advisory Panel for the project, including:

- Wojciech Zaremba, OpenAI co-founder

- Tom Kalil, CEO of Renaissance Philanthropy, former Chief Innovation Officer of Schmidt Futures and former Deputy Director for Technology and Innovation at the Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Matt Clifford, Co-founder and Chair of Entrepreneurs First, and founding Chair of ARIA, the UK’s Advanced Research and Invention Agency

- Additional advisors to be announced soon

What makes a good pitch

We are seeking initial short pitches (around 200–400 words) that address one of the three focus areas of this RFP: accelerating science, strengthening security, and adapting institutions. See “Ideas we are interested in” at the bottom of this post for full descriptions of these focus areas.

Your pitch should:

- Clearly explain the problem it aims to solve: why it is important (in terms of lives affected, dollars saved, etc.), and why market forces will not solve it fast enough by default.

- Lay out a specific, concrete solution, and how to build or implement it.

We are interested in projects that are particularly important to achieve in light of rapid advances in AI. This means that the capabilities of advanced AI — or the changes such capabilities will bring — should be a key part of either the problem or the solution.8 If you are unsure if a proposal is in-scope, we encourage you to submit it anyway.

A non-exhaustive list of the kinds of project ideas we’re excited about can be found at the bottom of this post. You can also see the project ideas we’ve already published on our website: ifp.org/launch.

Who should submit a pitch

We welcome pitches from two broad groups of contributors:

- Idea scouts: You have a concrete project idea (200–400 words), but don’t have the capacity to write a full project plan (under 2,000 words) yourself. If we then pursue your project idea with another author and publish a full project plan based on it, we will credit you and offer a $1,000 reward.9

- Authors and potential builders: You want to write (and potentially implement) a full Launch Sequence project plan like the ones on our website. Authors will receive a $10,000 honorarium upon publication of their piece.

We are especially interested in pitches from people who would consider implementing their proposal themselves.10 This is not a requirement; we are also interested in hearing from strategists, researchers, and domain experts who can articulate what technologies or projects should exist, even if they are not the ones to build them. We also offer a $1,000 bounty for successful referrals — if you know someone who might be interested in being an author, please share this page with them and ask them to include your name in the application form. If their proposal is accepted, you’ll receive the bounty.

How it works

- Submit a short pitch (200–400 words) via this form.

- If selected, you’ll be invited to write a more detailed outline.11

- If the outline is promising, we’ll work closely with you to develop a full project plan (under 2,000 words), with research, writing, and editorial support. We’ll help connect you with experts and turn your idea into a full proposal ready to be sent to philanthropic funders or policymakers.

- Published project plans become part of The Launch Sequence. We’ll help connect authors with funders, potential co-founders, and relevant policymakers.

We expect authoring full Launch Sequence project plans to take 8–14 weeks from accepted pitch to published piece, involving several stages of writing, receiving feedback from IFP and input from external experts, and refining your full project plan.

IFP is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, and will have no claim over any IP related to your idea, nor ownership of any resulting companies. We aim to accelerate authors and builders.

Submit your pitch

If you have an idea, we want to hear it. You can learn more and submit an idea via the form below.

This is a rolling RFP with no submission deadline, but we encourage you to submit a pitch early (within the next few weeks), as we will prioritize early submissions and start reviewing immediately.

Questions? Email launch.sequence@ifp.org

Ideas we are interested in

We are interested in rapidly building what we need to prepare for a world with advanced AI so that we can fully reap AI’s benefits while managing its new threats. Such an agenda will include a wide-ranging set of projects, including creating companies, tools, technologies, institutions, research streams, resources, and public policies.

We will only consider projects that address a market failure (or policy gap) and will therefore not be built by default, or not quickly enough. The three core categories where we expect these issues to surface are in accelerating science, strengthening security, and adapting key institutions.

The lists below are not meant to be exhaustive. Instead, they are meant to illustrate the kinds of projects that we would be excited to support. We encourage you to submit pitches for projects whether or not they are listed below.

Accelerating Science

What resources, technologies, or institutions will scientists need to unlock breakthroughs with AI and other emerging technologies, and which aren’t being created fast enough through market forces or traditional grant funding?

AI promises to transform how science is done. But leveraging AI advances for breakthroughs requires more than capable models. It requires infrastructure, institutions, and resources that no single lab or company has an incentive to build: shared datasets, standardized protocols, access to physical experimentation capacity, and new modes of peer review and validation. Traditional grant funding moves too slowly and often rewards the wrong things; private industry optimizes for what can become profitable, not what will most advance scientific progress. Without targeted investment and effort by the US government and philanthropies, scientific bottlenecks will limit AI-accelerated discovery even as the models improve. Below are non-exhaustive problem areas for which we are excited to receive submissions.

Health and biology. The highest ambition for AI may be to generate cures to inherited and infectious diseases. But even as AI companies pursue this goal, their efforts alone are unlikely to fully accomplish it: biology is immensely complex, wet lab work is messy and reliant on tacit knowledge, and treatments require extensive clinical trials and regulation before they can even start to be distributed to patients. And even if current technologies eventually scale to this lofty goal, delays, even on the order of years, will have massive life-altering costs for billions of people and avoidable suffering at scale. Moving faster, even to achieve the same outcome, can save millions of lives.

We are interested in proposals that offer ways to speed up biological research, decrease the time between a treatment’s discovery and its real-world availability, or create the policy entrepreneurship needed to massively improve healthspan around the world.

- Cutting down the time from a drug’s discovery to its widespread availability. Clinical trials can take years and are unnecessarily costly. Possible fixes include expanding the use of validated surrogate endpoints so trials can read out sooner; creating platform approvals for delivery systems so each new payload does not trigger a full re-review; and building distributed trial infrastructure so recruitment, monitoring, and data collection can run in parallel across sites, shortening timelines while lowering costs. Ultimately, speeding up regulatory timelines and lowering the costs of bringing drugs to patients will save time, money, and lives.

- Automation for small-scale labs. Most academic labs still rely on the manual labor of trainees to carry out tedious and repetitive experiments. Can inexpensive and easy-to-use robotic solutions be deployed to these labs to increase throughput and improve reproducibility, freeing up the researchers to develop new ideas?

- Better tissue-specific tools for drug delivery. AI could drastically accelerate the design process for creating custom gene therapies. But no matter how well-designed the payloads are, most types of cells in the body still cannot be specifically targeted so that these therapies end up where they are needed. New tools could unblock the cell-targeting bottleneck, allowing AI-accelerated gene therapies to start saving lives sooner.

- Characterizing the electrical properties of all neural cell types. The last decade brought massive investment in mapping the brain’s wiring (connectomics) and cataloging its cell types. But a wiring diagram alone does not tell you how the circuit behaves — for that, you also need to know the electrical properties of its components. When it comes to the human central nervous system, this foundational data is incomplete, limiting the efficacy of AI models of brain function in guiding treatments that target the precise mechanisms behind conditions like depression or bipolar disorder.

Novel infrastructure for the scientific process. AI tools are being developed to increase productivity in every industry, science included. However, while commercial interests are rapidly building AI tools for materials or drug discovery, efforts to improve the basic scientific process have received comparatively less attention. We are interested in “horizontal” infrastructure that improves the scientific process itself across fields. Projects to build better tooling for natural and physical sciences include:

- Scientific sampling at the edge. Billions of devices (phones, vehicles, drones, IoT systems) already carry sensors and compute which can be leveraged to perform privacy-preserving data collection and analysis at unprecedented scale — if we had the platforms and assurances to utilize them.

- Contractors that provide frontier AI solutions for basic science bottlenecks. Frontier Research Contractors (FRCs) with expertise in AI can use contracts and grants to fund AI research that solves basic science problems. Such FRCs could produce open and validated datasets, reproducible pipelines, tooling, and other integrations that help promising methods become reliable infrastructure.

- Extracting new scientific knowledge from AI models’ learned representations. Models trained on scientific data can learn representations of unknown natural laws. Extracting these laws in closed form would grow the corpus of scientific knowledge, lead to new hypotheses, and allow for more interpretable model design.

Metascience. Scientists spend a great deal of time on the work that surrounds the research enterprise — developing systems to durably maintain and share data, writing and reviewing proposals, and interacting with their supporting and partner institutions. Each of these areas of work is already being transformed by AI, but conventional grants and institutions are slow to catch up. Efforts to reimagine how institutions should adapt to the age of AI include:

- Requests for proposals that are robust to agentic grant writing. AI agents will create a glut of new mediocre grant proposals. We should engineer new calls for funding and submission vetting processes that are robust to this influx. Current solutions include capping the number of grants that one person or team can submit or focusing on person-based fixes, as opposed to fundamental process improvements.

- “Write for the AIs” publication standards. The advent of LLMs that can reliably parse and summarize hundreds of pages of text in seconds opens new opportunities for sharing high-detail scientific work. Scientific organizations should pilot new journal or repository standards that include structured metadata, full experimental context, code, lab notes, and data in machine-readable formats. Current papers are optimized only for human readers with limited attention; future science should experiment with bulk scientific data sharing.

- Replicating or reproducing important scientific findings. Reproducibility concerns still plague many areas of science. A large scaffold of AI agents using subsidized compute could sift through the important papers in a field to validate results and identify prime candidates for future reproducibility efforts.

Other potential directions. The above categories are non-exhaustive. We would also like to receive proposals for other scientific research directions, such as physics, chemistry, or ecology, or proposals that direct other unmet needs in the research, development, and innovation ecosystem.

Strengthening Security

What tools, technologies, or institutions can we build to ensure rapid AI advances do not undermine national security or public safety?

AI technologies are dual-use. The same capabilities that automate cyberdefense can automate cyberattacks; and the tools that accelerate progress in the life sciences may also reduce the barriers to engineer biological weapons. Furthermore, the transformative potential of AI raises the stakes of geopolitical competition, and strengthens the ability of state and non-state actors to cause widespread and asymmetric harm. No one actor bears these risks, requiring targeted philanthropic and government action to ensure that defenses can scale alongside AI capabilities. We are particularly interested in achieving a world in which defensive technologies are structurally advantaged, such that attacks are quickly detected and contained. Below are non-exhaustive problem areas for which we are excited to receive submissions.

Cyber defense. The integration of AI into cyber and cyber-physical systems introduces a broad range of vulnerabilities that hinder AI adoption and increase the attack surface for critical infrastructure. Moreover, AI is already increasing the speed and scale of cyber attacks. By proactively investing in security and leveraging AI for defense, we can enhance our resilience. Potential projects in this space include:

- Secure inference clusters. Design and build a frontier AI compute cluster for high-stakes applications that are required to be robust against cyber operations by even the most capable threat actors.

- Standardized tamper-proof modules. Design and open-source standardized tamper-proof modules that provide a root of trust at low cost and with high interoperability for mass-market applications.

- Fortified robotics. Implement defense-in-depth security architectures for robots deployed in critical contexts, including layers such as secure execution environments, tamper-evident sensors, formally verified software, redundant sensor cross-validation, and continuous anomaly detection.

- Training targets for formal verification. Develop benchmarks and RL environments to elicit AI capabilities for formal verification of complex systems, guiding model training to enable rapid hardening of digital infrastructure.

Biological defense. Advances in AI and biotechnology are removing barriers to the development and design of biological weapons, which could cause millions of deaths and trillions in economic damage. How can we prevent the worst outcomes without slowing down beneficial research? Potential projects in this space include:

- Passive air disinfection: Develop technologies like Far-UVC, next-gen in-room filtration or aerosolized disinfectants (like glycol vapors) that make indoor air pathogen-free by default and at commercial scale.

- Biothreat signal clearinghouse: Would-be bioterrorists leave subtle traces from AI chat logs to flagged synthesis orders. Most of these signals are not acute enough to justify reporting to law enforcement, but they paint a concerning picture when seen together. Create an NCMEC-style nonprofit that securely receives reports from DNA synthesis companies, equipment vendors, and commercial AI providers, aggregates weak signals, and forwards actionable intelligence to appropriate authorities.

- Non-pharmaceutical transmission blockers: Develop and validate interventions such as nasal sprays and oral rinses that mechanically block a wide variety of respiratory infections without drug use.

Verification and evaluation. AI challenges traditional technology-policy frameworks because it lacks many of the typical characteristics they address, like concrete physical forms, easily isolated components, and straightforward version control. To mitigate these problems, we need new methods for the verification of pertinent AI system characteristics (e.g., proving that certain data was used to train a model) and the measurement science of AI system capabilities and propensities (e.g., determining whether a benchmark accurately the risk-relevant properties it claims to). At the same time, these methods will not be effective if they leak or extract other critical information from the systems they are probing. Well-designed and privacy-preserving tools of this kind can enable a world in which governments can trust industry to manage this technology, and nations can credibly signal that their AI capabilities do not pose threats to international security. Potential projects in this space include:

- Workload verification. Design off-chip methods (e.g. FlexHEGs) that enable a developer or operator to prove their cluster only runs models passing a given evaluation without revealing model weights and data.

- Hardware inspection: Develop and deploy new techniques to detect whether AI accelerators have been backdoored, and whether they match a given specification.

- Robust evaluations. Develop a standardized set of tests and defenses to mitigate adversarial gaming of model evaluations; automate workflows to bring vulnerable evaluations up to compliance.

Alignment and control. AI systems demonstrate sophisticated, unintended behaviors as well as the capacity to evade human oversight. As AI agents take on more and more consequential tasks and play a greater role in our personal lives, the risks from alignment and control failures increase. These dangers could compound significantly as coding agents become more integral to AI development. Potential projects in this space include:

- Automated alignment workflows. Develop investigator agents to uncover internalized objectives in target models, balancing breadth of exploration and limits on context and memory.

- Agentic monitors. Create a monitoring agent that can surveil and probe an untrusted AI model in operation to identify indicators it is compromised, and develop methods to evaluate the trustworthiness of the monitoring agent.

Other potential directions. The former categories are not an exhaustive list of ideas we are interested in. Some other promising areas we would like to receive proposals for include:

- Privacy-preserving global threat monitoring

- Countermeasures for small unmanned aerial systems (UAS)

- AI tools for national security analysis (e.g., net assessment, intelligence briefings)

Adapting Institutions

What tools, technologies, organizations, or policies are needed to help society adapt to rapid AI-driven change while preserving human agency, individual freedoms, and democratic institutions?

The development of advanced AI would alter the very foundations of social and economic life. Translating AI’s potential into widespread flourishing requires forward-looking institutions12 and infrastructure — technological, organizational, and governmental — that can establish shared facts, coordinate at scale, and make rapid, well-informed decisions. Yet most existing systems were not built for the speed and complexity that AI enables, and markets lack the incentives to update some of these systems for this new reality. Below are non-exhaustive problem areas for which we are excited to receive submissions.

Increasing state capacity. Governments are slow-moving institutions, but it is imperative for them to respond quickly and competently to rapid AI progress. In a world of rapidly advancing AI, the US government has a crucial role to play as an enforcer of law and order, provider of public goods, and the R&D lab of the world.

- Policy enabling AI procurement and use in government. As AI becomes more capable, governments that do not leverage it risk falling behind those that do. We should lower barriers for government employees to use reliable AI systems in their workflows and start iterating early on security guidelines through real-world use.

- AI-enhanced policymaking. Develop tools that can simulate the results of public policy decisions, run strategic wargames across thousands of scenarios, or model how regulations would affect the population, giving policymakers faster feedback loops than current polling or pilot programs allow.

Epistemic integrity. AI dramatically lowers the cost of generating large volumes of apparently high-quality content, straining our ability to distinguish facts from fiction or propaganda. However, new infrastructure designed to establish ground truths, incorporate a variety of viewpoints in well-organized discussions, and analyze large amounts of data can create a more dynamic marketplace of ideas than ever before. We should be wary of interventions that give any one person, company, or interest group the power to adjudicate what is true and what isn’t — distributed solutions like Community Notes could instead provide less-brittle alternatives. Potential projects in this space include:

- Community Notes everywhere. Build the tools to allow human-driven Community Notes to be placed anywhere on the internet, beyond just social media. Alternatively, scale fact-checking and contextualization by using AI systems to replicate the bridging-based consensus mechanism of Community Notes.

- Provenance tracing. Build and roll out tools like C2PA that take a given piece of information and trace its origin, evolution, contextual connections, and propagation.

- Personhood credentials. Design a protocol and build infrastructure for provisioning privacy-preserving digital credentials that allow users to prove they are humans while using online services, without revealing personal or sensitive information.

Coordination. The costs of coordination — identifying counterparties, becoming informed, negotiating priorities and agreements, and ensuring adherence to terms — mean that many mutually beneficial agreements between people in the world never actually get made. Likewise, the cost of coordination hinders many individuals’ ability to participate in the governance decisions that affect their lives. AI could greatly reduce the costs of coordination, enabling individuals to reach positive-sum outcomes and directly participate in governance at unprecedented scale.

- Individualized models. Develop methods to customize AI models aligned with each individual’s specific goals, skills, and values, enabling agents to represent individuals in interactions with other agents, and helping keep humans economically relevant.

- Coordination and bargaining infrastructure. Build platforms and protocols that reduce the transaction costs blocking mutually beneficial agreements: tools for coalition formation that help diffuse interests coordinate, infrastructure for agents to negotiate terms on behalf of individuals while securely handling sensitive information, and arbitration protocols that enable rapid dispute resolution through credibly neutral AI mediators.

Building resources to maintain human agency. In recent history, people have maintained economic and political power because they were needed as workers, taxpayers, soldiers, and voters whose cooperation institutions depended on. As advanced AI automates increasingly large parts of the economy, the risk goes beyond broad unemployment — it’s that as people lose economic leverage, their institutional leverage will suffer too. If institutions can function without broad human participation, they may become less responsive to human needs. Markets and governments will likely produce some tools for adaptation, but may do so unevenly or too slowly to keep pace with AI progress. We’re interested in projects that help people maintain economic relevance and institutional leverage even as advanced AI automates large parts of the workforce.

We believe this effort is critical, but we are unsure as to what the most promising proposals in this area may be. Proposals in this category should make an especially strong case for why markets or other institutions won’t provide the solution fast enough by default. Possible proposals in this area include concrete programs to help people rapidly adapt their skills; human-in-the-loop tooling to enable workers to efficiently supervise, direct, and collaborate with AI systems at machine speed; and benefits-sharing programs or policies to ensure the broad automation of labor benefits the general population.

Other potential directions. The above categories are not an exhaustive list of ideas we are interested in. Some other promising areas we would like to receive proposals for include:

- Policies or institutional frameworks for assigning responsibility, liability, and oversight when decisions are made or executed by AI agents rather than humans.

- Adapting payments systems and other core economic infrastructure to a world where AI agents could initiate transactions, negotiate contracts, and control resources on behalf of humans or institutions.

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Gaurav Sett, Non-Resident Fellow at IFP, for closely consulting on this piece.

-

By “advanced AI” we mean highly autonomous systems that match or outperform humans at most cognitive tasks and economically valuable work. See “Ideas we’re interested in” below for more information.

-

More details under “Who should submit a pitch?”

-

AI could unlock treatments to the most debilitating human diseases. But some of these fundamental breakthroughs will lack clear commercial incentives or face other barriers. If AI greatly accelerates science, unaddressed bottlenecks will become especially acute, and proactively eliminating these bottlenecks will become especially important.

-

AI is a dual-use technology. Industry’s incentives to address AI misuse and other threats may be dwarfed by the scale of the risks new AI technologies may impose on the public. We should accelerate the development of defensive technologies ahead of the development of destabilizing ones.

-

We also submitted these proposals to the American Science Acceleration Project RFI, bound them into a beautiful book, and are sending copies to all 535 offices in Congress.

-

Submissions to the FDA for drug approval, which collectively form one of the most exhaustive repositories of real-world scientific practice and regulatory negotiation ever assembled, and thus a rich resource for AI to be trained on.

-

While the original Launch Sequence proposals were primarily aimed at the US government, we’re broadening our focus to include projects that can move forward just with philanthropic support. Given our new focus on providing shovel-ready ideas for funders, we will dedicate many more resources to vetting and refining project proposals than we did in the past.

Still, the US government can play a powerful role in implementing many proposals at scale, and we are excited to support proposals that require or benefit from government action.

-

This should be interpreted broadly, for example: a pitch for an organization to manufacture next-gen personal protective equipment (PPE) to increase society’s resilience against pandemics would be in scope. This is because future AI may democratize access to the knowledge and tools needed to create engineered viruses, thus increasing our baseline pandemic risk.

Examples with links to existing Launch Sequence project plans:

1. Cases where AI creates/worsens a problem (e.g., biosecurity, offensive cybersecurity, AI sleeper agents, securing AI model weights)

2. Cases where AI can be/support the solution (e.g., automating scientific replication, pathogen detection via metagenomics and ML, AI-powered code refactoring)

3. Cases where AI makes something newly feasible, which will not be done fast enough by default (connectome mapping, self-driving labs)

-

Note: You will be eligible for this bounty if: (1) we first learn about a particular project idea based on your pitch, and (2) you selected “I just want to submit an idea” in the application form, and (3) we then publish a full project plan based on your initial pitch.

We will ultimately determine whether we had already considered a project idea, or whether your pitch was the first time we encountered it. Only one person will be eligible for the “idea scout bounty” for every piece we publish.

-

If you're proposing a new research group or institution, we are excited to help accelerate the potential founder. If you're proposing a government program, we are excited to make the right connections and help the author make it happen.

-

We’ll aim to respond to initial pitches within a few weeks of submission, to allow time for us to investigate the area and consult with our advisors and domain experts.

-

“Institutions” in this RFP should be interpreted broadly, as “the humanly devised constraints that structure political, economic, and social interaction.”