- Download PDF

Executive Summary

International talent is necessary for US AI dominance. Two-thirds of the top AI startups were founded by immigrants and most PhD-level AI talent in the US is foreign-born. However, growing wait times in the immigration system and competition for talent threaten the US ability to recruit and retain the AI workforce.

We offer a suite of recommendations to cut red tape, make the immigration process more efficient, attract and retain AI entrepreneurs and AI researchers, and enhance national security.

1. The role of foreign talent in the AI workforce

The United States faces a persistent shortfall of highly-skilled AI professionals needed to sustain its leadership in artificial intelligence.1 The United States relies heavily on high-skilled foreign-born talent to sustain its AI workforce, allowing it to have a much more robust AI workforce than what it could achieve relying only on the domestic supply. Even with foreign talent, some technical AI occupations appear to face gaps in supply, most notably for computer and information research scientists.2 Among key technical AI occupations, the employment of computer research scientists has the strongest evidence of a persistent labor shortage, as demand has grown faster than supply has kept up given the time needed to train a research scientist. From 2015-2019, employment of computer research scientists grew by 73% while mean wages grew by 27%, four times as fast than the national average and faster than other STEM and computer occupations like software developers.3

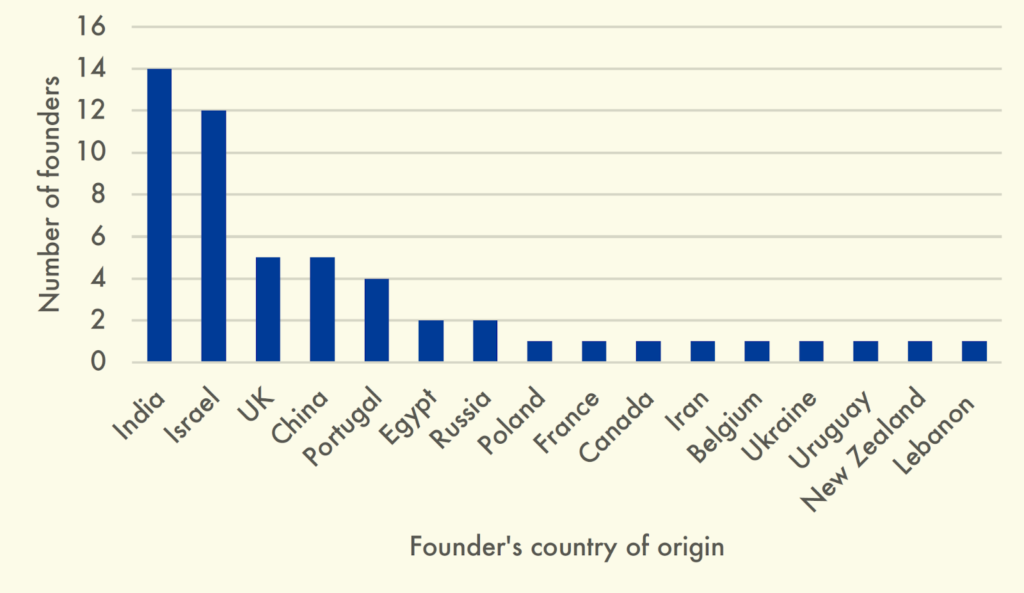

Foreign-born entrepreneurs play a critical role in driving AI innovation in the United States. Most of the country’s leading AI startups have been founded by immigrant entrepreneurs, contributing significantly to job creation, technological advancement, and economic growth. A CSET study found that of the 50 “most promising” US-based AI startups on Forbes’ 2019 “AI 50” list, 66% had an immigrant founder.4

Two thirds of the top AI startups have an immigrant founder, with India and Israel as leading countries of origin

CSET estimates that 72% of these immigrant startup founders first came to the United States on student visas. However, various restrictive visa rules create barriers for foreign-born AI entrepreneurs seeking to establish companies in the US. Rules also keep many people already here in the United States locked in academia, which gets preferential access to visas. Implementing policies to attract and retain AI startup founders, and allow researchers the authority to easily commercialize ideas, would bolster the AI ecosystem and ensure continued global competitiveness.

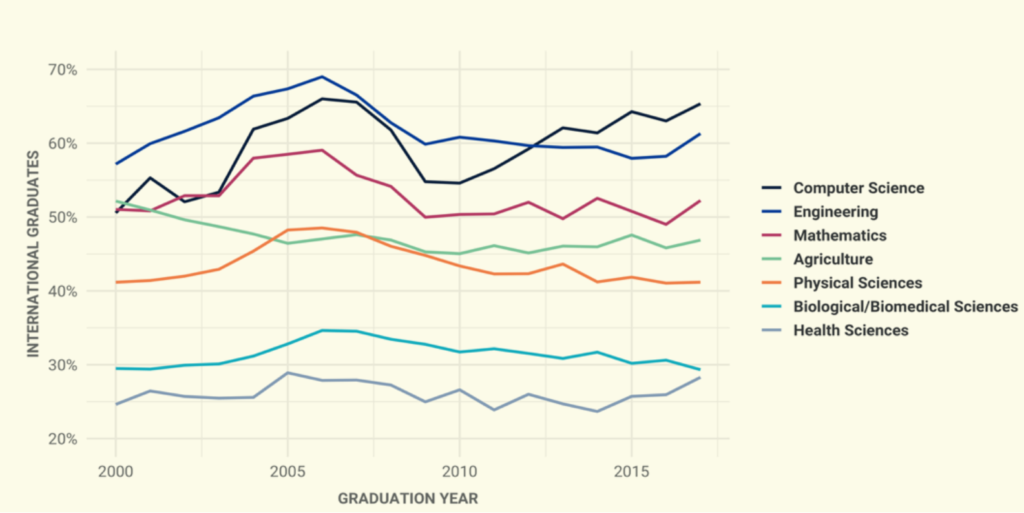

AI talent recruitment typically begins with US education. Foreign-born AI workers often enter the US as Bachelors, Masters, or Ph.D. students. Of the students who graduated from US STEM PhD programs from 2015 through 2017, more than half were foreign nationals.6

Most PhDs awarded by US institutions in computer science go to foreign-born graduates

2. Two forces may reduce US ability to attract AI talent

A high share of international PhD students in STEM fields intend to remain in the United States after graduation; of 2017 graduates from computer science PhD programs, 87 percent indicated that they intend to stay in the United States.8 Historically, the US has been successful in retaining these high-skilled individuals, benefiting from their contributions to research, industry, and entrepreneurship; according to CSET research conducted on 2017 data: “since 2000, at least 65 percent of every year’s graduating class has stayed in the United States.”9

Nevertheless, stay rates should be higher. But two forces threaten to reduce them.

Barriers to Immigration Have Increased

Current immigration policies pose barriers to retaining and attracting these professionals. Many AI workers enter the US as international students in STEM fields, but growing wait times for employment-based green cards, visa restrictions, and uncertainty in immigration policy have made it increasingly difficult for these highly trained professionals to stay.10 A CSET survey of AI PhDs found that of respondents who left the United States, one-third indicated that immigration constraints were highly relevant to their decision to leave.11

According to SEVIS data, the share of F-1 students requesting another status after completing a degree in the US peaked in 2007 and has fallen by over 30%.

Source: Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS).12

Making matters worse, growing backlogs for green cards translate into more time spent in legal status that deters entrepreneurship. This means that talented AI researchers who we do manage to retain are deterred by restrictions from using their talents in ways which will most advance the field. Leaving academia, which gets preferential access to H-1Bs, poses visa obstacles, as does starting one’s own company. Studies have found that the longer visa backlogs grow, the more STEM talent ends up “settling for academia” rather than the commercial sector, let alone entrepreneurship of their own.13

Other Countries Are Competing for AI Talent

Meanwhile, countries such as Canada, the U.K., and China are implementing targeted immigration policies to attract AI talent.14 The US risks losing its competitive edge as other nations provide streamlined visa pathways, fast-tracked permanent residency options, and national AI strategies that prioritize talent retention.

Meanwhile, global competitors, particularly China, are rapidly expanding their STEM workforce, producing more AI and STEM PhD graduates than the United States; in 2025, China is forecasted to nearly double the number of STEM PhDs.15 Without targeted immigration reforms and AI workforce investments, the US risks losing top AI talent to nations with more favorable immigration policies. Strengthening pathways for retaining international STEM PhD graduates is crucial to maintaining US leadership in AI innovation.

3. Policy Recommendations to Strengthen AI Workforce

To ensure the US remains the global leader in AI, we recommend the following immigration reforms:

A. Cut red tape and make the immigration process more efficient

Schedule A. The Schedule A shortage occupation list identifies occupations for which there are not enough American workers and streamlines the labor certification process for those occupations. Occupations on the list face shorter processing times, less paperwork, and greater certainty and predictability. When the list was first published in the 1960s it included engineers as well as PhDs in the sciences. However, the list has not been updated since the 1990s, and does not contain any STEM-related occupations (only nurses and physical therapists). Identifying occupations in AI on Schedule A would help prioritize those fields within the fixed pot of employment-based green cards, while cutting down on a lengthy bureaucratic labor certification process.

Special handling. Grant permanent labor certification via special handling to employers hiring advanced STEM talent in AI. The special handling process lets an employer secure labor certification by relying on their own competitive recruiting process when they found the best candidate was a foreign national of exceptional ability. Because DOL has never defined “exceptional ability in the sciences,” special handling currently only applies to universities and then only for teaching hires (not research-only faculty) but could be expanded to employers beyond academia who are hiring advanced STEM talent working on critical and emerging technologies (and for lab research scientists on campuses) like AI. One opportunity for special handling is to create a regulatory mechanism by which the National Science Foundation identifies key emerging technologies every three years that presumptively qualify for National Interest Waiver EB-2 I-140 Petitions.

Domestic renewal. Foreign AI researchers and engineers working in the U.S on temporary visas (like H-1B or O-1A) must interrupt their work at American AI companies, labs, and universities if they travel abroad, potentially facing months-long delays for visa renewal that disrupt critical research and development projects. Authorities under 22 CFR 41.111(b) allow less-disruptive domestic renewals, which were the primary means of renewing visas until 2004. A recent domestic renewal pilot program sunsetted in April 2024, but could be revived and expanded.

Premium processing for international entrepreneurs. Immigrant entrepreneurs face challenges due to the lack of a suitable visa option, forcing them to rely on visas intended for academics and employees of existing companies. This limitation not only makes the US less appealing to highly skilled immigrants but also hinders the growth of startups and small companies. Adding premium processing to the International Entrepreneur Rule program would reduce processing times, significantly increase startup founder confidence in this immigration pathway, and lead to higher utilization and expansion of early stage AI startups.

Deploying AI for visa processing. The administration should ensure that USCIS completes the digitization of immigration processing by 2027 on schedule, and pilot programs to develop and use AI programs to augment processing capacity of USCIS adjudicators and reduce processing times.

B. Attract and retain AI entrepreneurs and AI researchers

Dual intent for O-1A extraordinary ability. The O-1 visa classification has “quasi-dual intent” in both the State Department’s Foreign Affairs Manual and DHS regulations. However, many startup founders have learned this is insufficient and have their visa applications rejected at American consular posts for being unable to prove they don’t have immigrant intent. The Foreign Affairs Manual and regulations should be revised such that the O-1A becomes a status with unequivocal dual intent status.

Recapture unused green cards. While increasing the number of green cards is beyond the scope of the executive branch, the administration can ensure that all of the green cards Congress has already authorized get put to use. Over 300,000 green cards have gone unused which could be “recaptured” and made available to AI talent seeking employment-based green cards.

O-3 spousal work authorization. Recruiting O-1A aliens of extraordinary ability in the AI field requires that eligible foreign nationals believe that coming to the United States will make sense for themselves and for their families. Ensuring that the spouses of O-1As (who commonly are also highly-skilled) will have work authorization makes coming to the US a more attractive proposition to a prospective O-1A.

C. Enhance US national security

Launch Project Paperclip 2.0. The DoD should begin a proactive and targeted talent identification and recruitment program for the world’s top AI talent. As the House Select Committee on China suggested, the US should “execute a talent strategy” of its own. For example, this program may determine targets at Chinese AI labs who would be valuable to poach for defense purposes. China is actively using talent programs like Qiming to recruit foreign talent while the United States mostly relies on its universities alone. The US could learn from its own past of running targeted recruitment programs, from Project Paperclip, which recruited the German scientists who won the Space Race to the Soviet Scientists Act which denied experts to rogue post-Soviet states. The administration can begin by instructing federally funded research and development centers to build methodologies for talent identification, which can then be used to collaborate with the private sector on targeted recruitment.

H-1B2 visas. DoD can fully use its allotment of H-1B2s, a special set-aside of 100 visas for researchers working on a DoD cooperative research and development project or a coproduction project under a reciprocal government-to-government agreement administered by DoD. According to recent data, DoD only uses approximately 30% of its H-1B2 allotment. It could immediately work to use remaining visa slots by placing eligible targets in eligible AI-related projects using remaining visa slots.

Export control clarity for immigrant inventors. In order to encourage innovation and the commercialization of emerging and critical technologies, the government should issue clear guidance about how nonimmigrant researchers and inventors can comply with export control rules when they want to commercialize their technologies in startups in the United States. At present, many foreign-born innovators hesitate to create companies that directly contribute to the defense innovation base, because of ambiguities in how export control rules apply to them, given their immigration status. New guidance would give clarity, predictability, and certainty for immigrant entrepreneurs who have invented a new technology that is potentially subject to export control requirements, and specify how “deemed export” rules apply to foreign nationals who have created some technology themselves and when foreign nationals are allowed to seek an export control license.

-

Diana Gehlhaus, et al. “U.S. AI Workforce: Policy Recommendations,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (October 2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/20200087

-

Diana Gehlhaus and Ilya Rahkovsky, “U.S. AI Workforce: Labor Market Dynamics,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (April 2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/20200086

-

Ibid.

-

Tina Huang, Zachary Arnold, and Remco Zwetsloot, “Most of America’s ‘Most Promising’ AI Startups Have Immigrant Founders,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (October 2020). https://doi.org/10.51593/20200065

-

Ibid.

-

Remco Zwetsloot, Jacob Feldgoise, and James Dunham, “Trends in U.S. Intention-to-Stay Rates of International Ph.D. Graduates Across Nationality and STEM Fields,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (April 2020). https://doi.org/10.51593/20200001

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid.

-

Jack Corrigan, James Dunham, and Remco Zwetsloot, "The Long-Term Stay Rates of International STEM PhD Graduates," Center for Security and Emerging Technology (April 2022). https://doi.org/10.51593/20210023

-

Zachary Arnold, Roxanne Heston, Remco Zwetsloot, and Tina Huang, "Immigration Policy and the U.S. AI Sector: A Preliminary Assessment," Center for Security and Emerging Technology (September 2019). https://doi.org/10.51593/20190009

-

Tina Huang and Zachary Arnold, “Immigration Policy and the Global Competition for AI Talent,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (June 2020). https://doi.org/10.51593/20190024

-

Jeremy Neufeld and Divyansh Kaushik, “International Talent Flows to the United States,” written for National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, “International Talent Programs in the Changing Global Environment” (February 20, 2024). https://nap.nationalacademies.org/resource/27787/Neufeld_and_Kaushik_ITP_Commissioned_Paper.pdf

-

Catalina Amuedo-Dorantes and Delia Furtado, “Settling for Academia? H-1B Visas and the Career Choices of International Students in the United States,” IZA (August 2016).

-

Tina Huang and Zachary Arnold, “Immigration Policy and the Global Competition for AI Talent,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (June 2020). https://doi.org/10.51593/20190024

-

Remco Zwetsloot, et. al., “China is Fast Outpacing U.S. STEM PhD Growth,” Center for Security and Emerging Technology (August 2021). https://doi.org/10.51593/20210018