This is the second piece in the Proxy Praxis series, which examines how surrogate endpoints shape and could accelerate drug development. The series explores both the promise and the risks of surrogate endpoints, how the FDA governs their use and influences innovation incentives, and reforms that could encourage the development of more reliable endpoints while curbing reliance on weak or inappropriate ones. An overview of the series is available here.

Introduction

The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in 2016, aimed to unlock the potential of surrogate endpoints. By establishing the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP), the Act sought to create a formal pathway for transparently and scientifically validating biomarkers that aid drug development.

The introduction of BQP should have signaled an era of increased transparency and standardization at the FDA. The BQP pathway offers the opportunity for surrogate endpoint qualification under a transparent framework: once a biomarker is approved for a defined use, any sponsor may adopt it without reopening negotiations.

Yet surrogate endpoint validation remains a slow process — constrained by siloed clinical trial data, chronic underinvestment driven by misaligned incentives, and a cumbersome regulatory pathway. Nearly a decade later, only one surrogate endpoint has been fully validated under BQP, approval for which took nine years. The FDA largely continues to largely rely on case-by-case negotiations with sponsors, the very approach the program was designed to replace.

The first and only team to qualify a biomarker for use as a surrogate endpoint in pivotal trials under BQP is the Study to Advance Bone Mineral Density as an Endpoint (SABRE). SABRE focused on osteoporosis trials and substituted Bone Mineral Density (BMD) for the usual clinical endpoint, which is fracture outcomes. Adoption of BMD as a surrogate promises to dramatically reduce trial duration and cost. SABRE achieved qualification of BMD as a surrogate endpoint on December 19th, 2025, 12 years after the initiative began.

The protracted timeline of the SABRE project is puzzling for two reasons. First, the effort did not involve the discovery or development of a novel biomarker: Bone Mineral Density (BMD) has been in routine clinical use since the 1980s and has served as the standard diagnostic measure for osteoporosis for decades. Second, no new data generation was required. Because BMD is measured in virtually all osteoporosis trials, the evidence needed for validation already existed.

That fact it nonetheless took more than a decade to validate BMD as a novel biomarker points to a set of barriers that systematically obstruct surrogate endpoint validation.

- Existing clinical trial data are systematically underutilized. Although all the evidence required to validate BMD already existed, it was fragmented across pharmaceutical companies and sponsors. This turned what should have been a straightforward meta-analysis into years of negotiation and labor-intensive data assembly.

- Surrogate endpoint validation is a public good with deeply misaligned incentives. Once a biomarker is qualified, its benefits accrue to an entire therapeutic area, yet there is no intellectual property protection and no clear path to direct monetization. The costs, however, are borne by a small number of willing sponsors, deterring private investment. As a result, SABRE raised only around $2 million — negligible relative to the cost of a single fracture-endpoint trial — leaving the effort chronically under-resourced despite its high social value. Academia does not compensate for this gap, as academic incentives reward the discovery of new biomarkers rather than the slow, demanding validation of existing ones.

- The FDA’s BQP remains slow and opaque, further weakening incentives to pursue formal qualification. Together, these barriers help explain why SABRE took more than a decade to complete — and why its implications are sobering. If validating a well-established, routinely measured biomarker such as BMD required over 10 years, then the validation of newly discovered biomarkers — where data must first be generated rather than aggregated — may reasonably be expected to take several decades under the current system.

Osteoporosis: a therapeutic area bottlenecked by clinical trial costs

Osteoporosis is a progressive bone disease that reduces bone strength, increasing the risk of fractures. In the US, it affects more than 10 million people, predominantly post-menopausal women. It carries serious consequences, with hip fractures alone being associated with a 25% chance of dying within a year, and only around 50% of survivors regain their pre-fracture level of mobility. Direct costs due to osteoporotic fractures in the US are projected to rise to $95 billion a year by 2040, up from $22 billion in 2008.

Despite this burden, the disease remains underdiagnosed and undertreated. Fewer than 15% of patients who have sustained a fracture receive therapy. In addition, the most effective drugs are less likely to be prescribed than older, less potent ones, mostly due to safety concerns and ease of administration. In addition, as Dr. Willard Dere1 explained that more potent and safer therapies with shorter treatment timelines are needed to correct the undertreatment of the disease.

Despite the unmet need, therapeutic innovation in the area has stagnated in recent decades. Since the discovery of bisphosphonates in the 1960s and subsequent improvements within this class (culminating with the approval of alendronate in the late 1990s), few novel and more potent drugs have reached patients. The most recent approval, romosozumab in 2019, saw limited patient adoption due to cost, delivery mechanism (via injections), and cardiac risk warnings. A review of ClinicalTrials.gov reveals a thin pipeline, with few drugs in clinical trials. The most advanced candidates include Entera Bio’s EB613, the first oral anabolic agent, and Angitia’s AGA2118, a bispecific antibody currently in Phase II trials.

At first glance, we should expect far more osteoporosis drug development. The market is large, and the need is unmet. Additionally, osteoporosis has a good translational model, in the form of a highly predictive animal model for the disease. By removing the ovaries of a rat, researchers can produce a model of bone loss that mirrors the human condition both mechanistically and phenotypically.

Why then are we not seeing more innovation? The answer is complex, but lies in large part with the prohibitive costs of osteoporosis clinical trials. Phase III trials in osteoporosis that measure fractures typically require 10,000 to 16,000 participants, often run for 3–5 years or more, and cost upwards of $500 million (and in some cases over $1 billion). For example, Merck’s odanacatib program lasted 12 years and enrolled more than 16,000 women. Despite meeting efficacy endpoints, the program was abandoned after a post-hoc safety analysis showed increased stroke risk. The cost of development was estimated at around $1.6 billion in today’s money, a large fraction of which went toward clinical trials. Romosozumab, meanwhile, required two pivotal trials involving over 11,000 participants.

SABRE sought to dramatically alleviate these prohibitive costs. There is strong evidence that the adoption of BMD as an endpoint would increase investment in the space. Both the cost and duration of clinical trials would be dramatically reduced, with estimates of 500–1,000 patients and less than 18 months trial duration, which could slash trial costs to under $100 million.2 Results from the economic literature suggest large increases in investment in a disease area should be expected as a direct consequence of such reductions in costs and timelines.

These results have been supported by interviews we conducted with experts and developers in the field, who confirm that the conclusions apply to osteoporosis. Miranda Toledano, the CEO of a clinical biotech firm developing EB613, one of the two osteoporosis clinical stage drug candidates, confirmed that Phase III clinical trials with fracture as an endpoint would be prohibitively expensive for a small company like hers.

Making osteoporosis trials cheaper and faster is especially urgent because science is opening up new possibilities. Dr. David Roblin is the CEO of a biotech startup who previously held senior roles at large pharmaceutical companies. He explained that tools like DNA large language models and multi-omic maps are beginning to reveal the molecular pathways that causally drive osteoporosis. However, he highlighted that unless there are practical and affordable ways to measure clinical outcomes in trials, these scientific breakthroughs risk stalling at the research stage, rather than translating into new therapies for patients. This was echoed by Dr. Alan Ezekowitz, a physician-scientist and biotech veteran now advising a large biotech venture capital and creation firm. He explained that many promising new targets for osteoporosis, some genetically validated, have emerged in recent years, but remain commercially unattractive due to the high cost of fracture-based trials. “If BMD were qualified,” he said, “it would meaningfully shift how investors think about this space.”

The SABRE story

In 2008, Dr. Mary Bouxsein, Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School, made a case for developing surrogate endpoints in osteoporosis. She noted that the existence of partially effective therapies was raising the evidentiary bar for new drugs. Because fractures occur infrequently, detecting these improvements would demand very large sample sizes and extended follow-up, making trials prohibitively expensive and slowing further innovation.

Five years later, in 2013, she co-founded SABRE with an international group of academics.3 Supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) and the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR), SABRE set out to assess whether BMD could serve as a reliable surrogate endpoint by pooling individual patient-level data from more than 150,000 participants in 50 randomized controlled trials and analyzing the relationship between risk of fracture and change in BMD.

The most time-consuming part of running SABRE was not scientific, but logistical. As explained by three of the leaders of SABRE (Drs. Mary Bouxsein, Richard Eastell, and Dennis Black), simply gathering the existing data took monumental effort. Results from clinical trials were scattered across numerous companies and research groups, each subject to its own regulatory, legal, and logistical constraints. Many datasets had changed ownership through licensing or mergers, requiring extensive detective work to locate each. Sponsors were generally willing to cooperate, but the transfer process was slow, often due to the need to negotiate legal requirements, and because ongoing trials could not share interim results.

Data availability has not substantially improved since SABRE’s founding in 2013. Valuable trial data for biomedical research remains siloed within institutions and companies, and bringing it together for secondary use requires enormous effort. Although third-party individual patient-level data from clinical trials sharing portals like Vivli, YODA, and BioLINCC have been created, they suffer from multiple problems that impede efficient and comprehensive meta-analyses. The most important is the fragmentation of the existing data. As biomarker researcher Dr. Joshua Wallach explained, datasets are distributed across non-interoperable systems, making large-scale analysis slow and resource-intensive. Usability audits show many portals provide only minimal dataset previews, require separate applications for each study, and lack consistent cross-links to ClinicalTrials.gov. All of these harm discoverability and transparency, slowing down research, and in some cases preventing certain meta-analyses entirely.

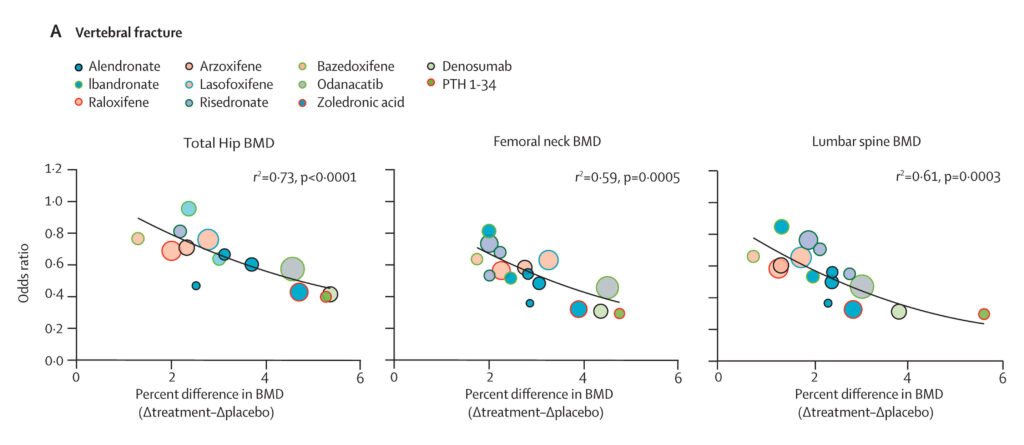

By 2018, the SABRE team aggregated and analyzed individual-level patient data from previous trials. The results — published in 2019 and 2020, along with a retrospective summary in 2025 — confirmed a significant association between treatment-induced changes in BMD and fracture risk.

The results of the meta-analysis showed evidence to support BMD as a surrogate marker for fracture outcomes. For vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, at least one BMD measure achieved an R² above 0.65, a benchmark often cited as “strong surrogacy.”

Figure 1. Association between treatment-induced changes in bone mineral density and incidence of vertebral fractures. Source.

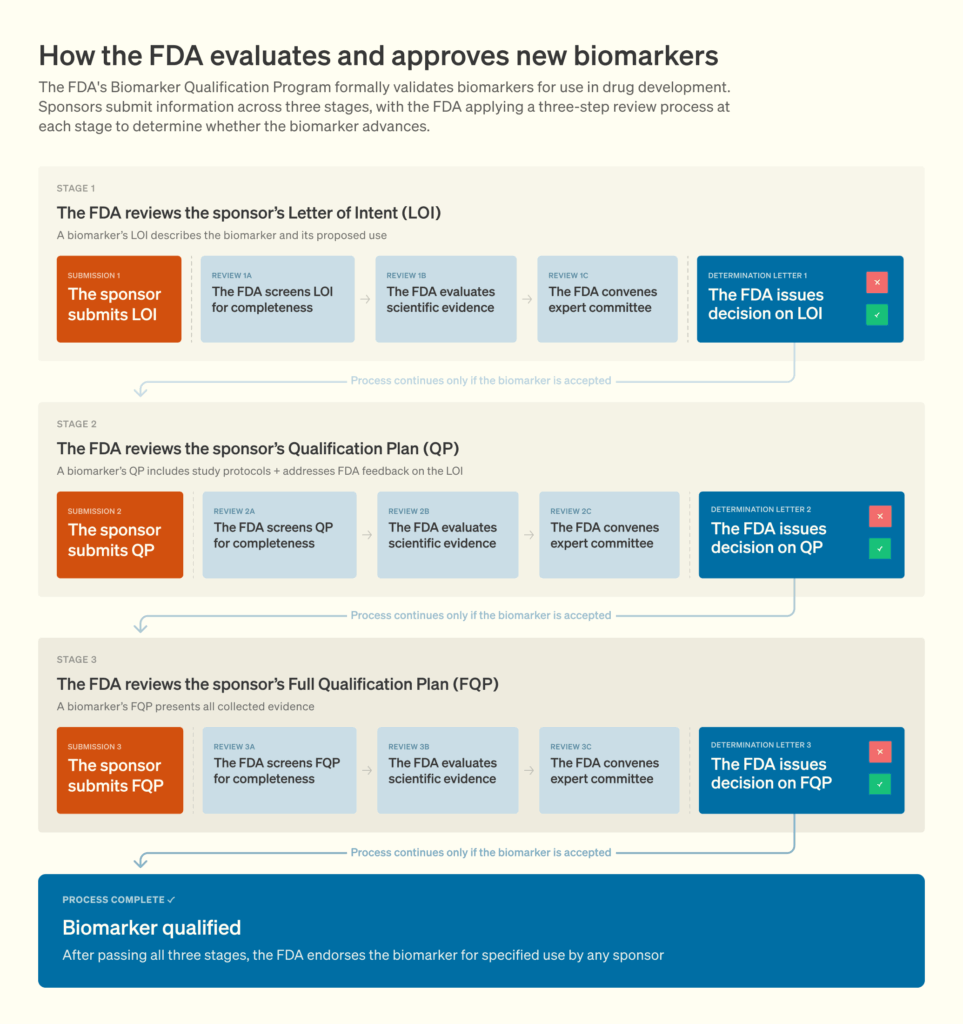

SABRE also carried the burden of being the first attempt to qualify a surrogate endpoint under the 21st Century Cures Act. This naturally involved close scrutiny from regulators. The Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP) follows a three-stage process — submission and review of a Letter of Intent (LOI), a Qualification Plan (QP), and a Full Qualification Package. Each step entails extensive iterative engagement with the FDA to establish evidentiary standards and resolve data gaps. SABRE’s initial Letter of Intent was submitted in 2018, initiating a prolonged regulatory process that has now spanned seven years. Although prior academic literature provided some guidance, the qualification pathway was largely uncharted before SABRE. The SABRE leaders expressed hope that their experience, documented through multiple studies and commentaries, would serve as a roadmap for future efforts.

Figure 2. The Biomarker Qualification Program process. Source.

Compounding the difficulty, SABRE was not undertaken by a dedicated consortium solely focused on biomarker validation. Instead, it was the initiative of a small group of academics who, despite their expertise in relevant areas, advanced the project alongside their broader teaching, research, and clinical responsibilities. As Dr. Bouxsein put it: “This was a passion project.” That it progressed as far as it did is a testament to the persistence and commitment of the investigators.

More funding might have eased the burden and reduced timelines. As Dr. Black noted, simply hiring more staff to handle data logistics and acquisition would have sped up the process. Instead, SABRE scraped by on roughly $2 million for more than a decade, mostly from private sponsors.4 At times, the team had to patch together small grants, accepting support from sources like the National Dairy Council. While $2 million might seem substantial, it pales in comparison to the cost of a single Phase III osteoporosis trial, which often exceeds $500 million.

The lack of funding reflected deep, structural issues. Pharmaceutical companies provided most of the funding, but still placed low priority on the effort. Consistent with the economics of a public good, the costs of developing a surrogate endpoint are borne by a few actors, while the benefits accrue broadly across the field.

An additional barrier that limits private investment is the length of the regulatory qualification process itself. Qualifying new biomarkers or surrogate endpoints is a slow process, with timelines that often exceed the duration of a company’s clinical development program in a given disease area. As a result, the benefits of a validated surrogate may materialize only after a company has advanced, terminated, or deprioritized programs in the disease related to the endpoint.

Government support was also extremely limited, constituting only a small part of the total SABRE budget. This points to a broader misalignment, with traditional funding sources tending to prioritize novel discovery over clinical validation.

Even after overcoming the hurdles of data collection, being the first team to navigate the BQP process, and the challenges of limited funding, SABRE encountered another obstacle: regulatory timelines. Unlike most drug approvals, where the FDA typically issues a decision within about six months of a final submission, the review for BMD has taken much longer. The FDA accepted a full qualification plan from SABRE in 2022,5 and in March 2024 it issued a public notice that a final decision would be made by January 2025.

In a surprising twist, in July 2025, EnteraBio was granted permission by the FDA to run its Phase III, pivotal trials using BMD as an endpoint, without waiting for the full qualification of BMD. While this news is positive for SABRE and osteoporosis drug development, it does go against the ethos of why the BQP was established in the first place. Understandably, sponsors still negotiate the use of old, legacy surrogate endpoints on an ad hoc basis with the FDA, since full requalification of all of them through the BQP would entail substantial effort. However, doing the same type of negotiation for surrogates undergoing BQP defeats the purpose of the Act. Overall, this is part of a broader problem related to a lack of regulatory transparency and consistency when it comes to surrogate endpoints, which has been discussed by others and will be explored in other parts of the series.

BQP is underutilized

Stepping back from the case of BMD, a broader look at all surrogate endpoints currently progressing through the BQP shows that the challenges SABRE encountered are not isolated. Although the BQP was intended to accelerate the development of tools that could streamline drug evaluation, only five biomarkers are actively moving through the program today — a surprisingly low number given the potential impact validated surrogate endpoints can have on trial efficiency and cost. This adds weight to the broader observation of underinvestment in qualifying endpoints.

Two of these biomarkers have private sponsors, and both concern the same endpoint: liver stiffness. In each instance, the sponsor both funded the validation work and owned the proprietary measurement technology. This demonstrates that when clear financial incentives exist, private entities are willing to invest in surrogate endpoint qualification. However, absent such incentives, participation appears limited.

Regulatory timelines also show a consistent pattern, although the data here is very limited. Only two of the five biomarkers had been formally submitted to the FDA through a Letter of Intent prior to 2025 — BMD in 2018 and the composite endpoint for immunosuppressive therapies in 2019 — and both have faced prolonged review periods.

To better understand the evidentiary demands placed on sponsors, we reviewed the supporting materials for the three biomarkers with publicly available Letters of Intent or Qualification Plans. In all cases, the evidence base relied heavily on clinical trial datasets rather than observational cohorts or other forms of data. This reinforces a key point raised earlier: access to historical clinical trial data is essential for qualifying new surrogate endpoints. Without broader availability of such datasets, the process of validation will remain slow and inaccessible to many potential contributors.

Conclusion

The SABRE story highlights a striking misalignment between the promise of the BQP and its real-world execution. On paper, BMD should have been a case where a quick validation process, whether leading to a negative or positive decision, would be expected: the biomarker has a known mechanistic basis, is already embedded in clinical practice, and has decades of interventional trial data alongside fracture outcomes to analyze the relationship. The fact that the process nevertheless took so long highlights three key lessons.

First, data underutilization is a major barrier to medical advances. The SABRE team had to spend years locating, negotiating, and aggregating trial datasets scattered across companies, universities, and sponsors, despite the fact that all of the data already existed. The lack of a unified infrastructure for secondary use of data turned what should have been a straightforward meta-analysis into a decade-long endeavor. This extends beyond the validation of surrogate endpoints and has implications for any meta-analysis that would benefit from access to clinical trial data.

Second, this case study reveals a misalignment of funding incentives. Developing and validating surrogate endpoints is a classic public good: the benefits are distributed across an entire field, but the costs fall on whoever undertakes the task. SABRE raised only $2 million, which is a small amount compared to the hundreds of millions required for a single osteoporosis trial with fractures as an endpoint, and struggled to secure sustained support. The lack of public investment, coupled with the absence of private incentives, left the initiative under-resourced, despite its potential to reduce the costs of drug development.

Third, the BQP regulatory framework is not well-aligned with market incentives, stemming both from its slow timelines and its lack of transparency. Given its potential to shape an entire field, it is reasonable for the FDA to exercise greater caution when approving a surrogate endpoint. But the combination of a lengthy process and persistent lack of transparency risks further discouraging the qualification of surrogate endpoints.

This piece would not have been possible without the generous time that was offered by a large number of people working in both industry and academia, all of whom are named throughout the article. We would like to thank Dr. Willard Dere, Dr. Alan Ezekowitz, Dr. Mary Bouxsein, Dr. Richard Eastell, Dr. Dennis Black, Ms. Miranda Toledano, Dr. Joshua Wallach and Dr. David Roblin for generously taking their time to discuss various aspects related to this piece.

Appendix

Additional resources

- Richard Eastell, Terence W. O’Neill, Lorenz Hofbauer, Bente Langdahl, Ian R. Reid, Deborah Gold and Steven Cummings, Postmenopausal osteoporosis, September 2016.

- Oriana Ciani, Mark Buyse, Mike Drummond, Guido Rasi, Everardo D. Saad and Rod Taylor, Use of surrogate endpoints in healthcare policy: a proposal for a validation framework, June 2016.

- Enlli Lewis, Not all clinical trial data in the US are fragmented, June 2025

- Dennis Black, Austin Thompson, Richard Eastell and Mary Bouxsein, Bone mineral density as a surrogate endpoint for fracture risk reduction in clinical trials of osteoporosis therapies: an update on SABRE, June 2024

On prior uses of BMD as a surrogate endpoint

Long before the current qualification effort, BMD was used as a surrogate endpoint in osteoporosis trials. However, its regulatory credibility declined in the 1990s following a key study that challenged its predictive value. The turning point was a pivotal trial showing that fluoride therapy, while increasing BMD, failed to reduce fracture risk. Subsequent mechanistic studies revealed why: fluoride alters the chemical composition of bone by replacing hydroxyl groups in hydroxyapatite to form fluorapatite, producing tissue that is denser but more brittle.

This case fundamentally reshaped perceptions of BMD as a surrogate endpoint. Yet it is now clear that the fluoride story was mechanistically exceptional. Fluoride exerts its effects through direct physicochemical alteration of the bone structure, not by modulating bone turnover or remodeling. By contrast, virtually all other osteoporosis drugs fall into two mechanistic categories: antiresorptives (e.g., zolendronic acid), which slow bone breakdown, and anabolics (e.g., romosuzumab), which stimulate new bone formation. Unlike fluoride, which alters bone chemistry directly, these drugs act through cellular regulation of bone remodeling, preserving or improving bone microarchitecture and material strength. Under today’s pre-IND standards, which require evidence of a consistent, mechanistic link between BMD and bone strength in at least one validated animal model, such a compound would not progress to clinical testing. The fluoride results, while historically pivotal, are thus largely irrelevant to the mechanisms through which most osteoporosis drugs act.

A second, more minor blow to BMD’s status as a surrogate endpoint came from a 1991 etidronate trial showing an apparent increase in fractures during the third year of treatment among one patient subgroup. The investigators cautioned that several fractures were trauma-related and that the observed difference likely reflected random variation in a low-frequency event. Furthermore, etidronate overall reduced fracture risk compared with controls. It is highly likely that, had it not been for the earlier fluoride experience, these equivocal data would have been dismissed as statistical noise. However, the fluoride episode had so strongly shaped perceptions that even weak or context-dependent evidence, such as the etidronate anomaly, was interpreted through a lens of heightened skepticism toward BMD as a surrogate endpoint. Starting with the mid-1990s, osteoporosis drugs have been approved on the basis of large, fracture-based trials.

Evidence for qualifying an endpoint

The FDA provides guidance on the level of evidence required to validate a surrogate endpoint, but this guidance remains relatively general. In contrast, the scientific literature provides more detailed criteria for the type and strength of evidence needed, though alignment between regulatory and academic standards is not always guaranteed.

According to these academic frameworks, assessment of BMD as an endpoint appears to have relied on the highest evidentiary standard, level 1 evidence. This requires robust demonstration of a consistent relationship between treatment effects on the surrogate endpoint and on clinical outcomes, ideally supported by data from multiple randomized trials.

While surrogacy is not determined by a single statistic, R² is the most commonly used measure. An R² of 0.65 is often cited as indicative of “strong surrogacy,” though regulators and the scientific community generally view such thresholds as informative rather than prescriptive. For example, diastolic blood pressure, a well-established surrogate for stroke, has an R² of only 0.58.

For vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, at least one BMD measure surpassed the 0.65 benchmark, supporting strong surrogacy. Hip fractures showed lower R² values due to their rarity and greater uncertainty in estimates. To account for this, the authors applied meta-regression to identify a clinically meaningful threshold, finding that a 3.18% increase in total hip BMD predicts a significant reduction in hip fracture risk. Importantly, only treatments with demonstrated efficacy in large clinical trials, such as denosumab and zoledronic acid, exceeded this threshold.

-

A biotech industry veteran who led the development of several osteoporosis drugs, including denosumab.

-

The exact number of patients and duration would depend on pre-clinical efficacy data and trial design, so only estimates can be given. Dr. Richard Eastell suggested around 500 patients would be needed for a pivotal trial, while other sources leaned more towards 800–1,200 patients.

-

SABRE was the result of a large-scale collaboration between a number of academics spanning a large number of disciplines. Of the leaders of SABRE, we interviewed Dr. Mary Bouxsein, Dr. Richard Eastell, Professor of Bone Metabolism at the University of Sheffield, UK, and Dr. Dennis Black, Professor of Biostatistics at UCSF, US, for this case study.

-

Companies involved included AgNovos Healthcare, Amgen, Inc., Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme LLC, and Roche Diagnostics Corporation.

-

A full qualification plan under the FDA’s Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP) is a detailed submission that outlines the evidence, study designs, and analyses a sponsor will generate to demonstrate that a biomarker can be reliably used as a surrogate endpoint in regulatory decision-making.