In drug development, speed is critical. Each additional year a clinical trial takes can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, due both to ongoing trial expenses and the loss of valuable market exclusivity — the limited period during which a company has exclusive rights to sell a drug and can recoup its enormous R&D investments.

One way to shorten trials is through the use of surrogate endpoints. Traditionally, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves drugs based on clinical endpoints: direct measures of patient benefit.1 These endpoints are definitive but often slow to observe, sometimes requiring years of follow-up. To accelerate development, regulators may rely on surrogate endpoints: measurable intermediate biological signals that reliably predict clinical benefit, such as biomarkers or imaging readouts. Rather than waiting years, surrogate endpoints predict clinical outcomes earlier, dramatically reducing the time and cost required to generate meaningful evidence in humans.

By lowering the cost and duration of clinical studies, surrogate endpoints make it possible to run more trials, test more hypotheses, and learn more quickly from failure — goals that sit at the core of Clinical Trial Abundance. A system with abundant, efficient trials is more likely to identify which treatments truly work, attract sustained private investment in medical innovation, and ultimately move us closer to what matters most: more effective therapies reaching more patients, sooner.

Yet behind this apparent simplicity lies a more complicated story. Within the biomedical community, surrogate endpoints are either treated with suspicion or revered with great hope. For example, many longevity researchers hope to discover new surrogate endpoints that reliably capture the aging process and unlock a path to approval for longevity drugs. By contrast, important voices in oncology, where surrogate endpoints have largely formed the basis for approval in recent decades, worry about an overreliance on these metrics.

The promises and perils of surrogate endpoints

Opposing views on surrogate endpoints reflect a real tension between the enormous potential of well-validated surrogate endpoints to accelerate progress and the imperfect, sometimes misguided, and overly broad ways surrogate endpoints have been applied in practice.

This contradiction can hold even within the same therapeutic area. For example, in advanced colorectal cancer, the surrogate endpoint of progression-free survival (PFS) is highly predictive of the relevant clinical endpoint of overall survival. But that same surrogate endpoint shows little validity in breast cancer. Here, it has been used to approve drugs (e.g., bevacizumab) that were later withdrawn when confirmatory studies revealed no effect on survival.

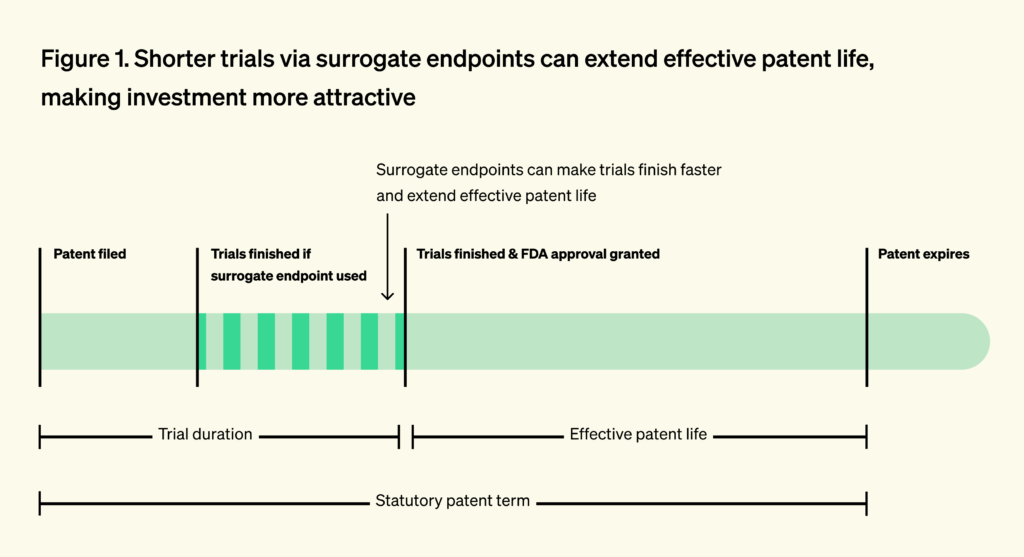

Beyond speeding access for patients, surrogate endpoints also reshape R&D incentives. Because inventors file near discovery and long before FDA approval, shortening trials preserves more of the patent term and increases expected returns. The value of time on-patent is clear in the market: priority review vouchers, which shorten FDA review time by four to six months, routinely sell for over $100 million.

Conversely, longer development timelines erode effective market exclusivity, reducing the time a company can sell the product without generic competition. This discourages investment in diseases with long survival times, where trials must run for many years. In oncology, for example, capital has historically flowed toward cancers with short survival, where outcomes can be measured quickly.

A 2015 study found that hematological cancers (where the FDA relies on short-term surrogate endpoints in 92% of approvals) attracted 112% more private R&D investment than solid tumors (where the FDA relies on surrogate endpoints in only 53% of cases). The study directly linked the differences in private investment to shorter clinical trial duration enabled by surrogate endpoints. The authors estimated that each one-year reduction in commercialization lag increased R&D investment by 7-23%. This underscores how valid surrogates can preserve effective patent life, boost expected returns on investment, and rebalance innovation efforts toward treatments for earlier-stage disease.

However, reliance on poorly validated surrogate endpoints can lead to the approval of drugs that fail to deliver meaningful patient benefit, diverting resources toward ineffective therapies.

In 2021, the FDA approved aducanumab, a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, under the accelerated approval pathway. The evidence for the drug’s efficacy rested on its ability to reduce amyloid plaque burden, a long-standing but controversial biomarker of the disease. Multiple large trials had already shown that clearing amyloid did not reliably slow cognitive decline. Nevertheless, the agency moved forward, citing amyloid reduction as “reasonably likely” to predict benefit.

The fallout was immediate. Three members of the FDA’s advisory committee resigned in protest. With a list price of $56,000 per year, aducanumab threatened to impose tens of billions of dollars in annual costs on Medicare alone. In this unusually egregious case, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services ultimately restricted coverage, and the drug was later withdrawn from the market. A Congressional investigation later faulted both the scientific rationale and the approval process. Altogether, it was a years-long detour for the field.

Unfortunately, many drugs approved on the basis of weakly validated surrogate endpoints face no such reckoning. In oncology, multiple analyses have shown that even when post-approval studies fail to demonstrate improvements in overall survival, drugs approved on the basis of surrogate endpoints typically remain on the market and continue to be reimbursed.

What is a (good) surrogate endpoint?

At the core of drug development lies a deceptively simple question: how do we know a therapy works? Regulators, clinicians, and patients ultimately care about clinically meaningful outcomes — how a person feels, functions, or survives. Clinical endpoints measure these outcomes, and good surrogate endpoints well approximate clinical endpoints.

A clinical endpoint is a direct measure of patient benefit. Examples include overall survival, prevention of stroke, or recovery of mobility. Clinical endpoints are meaningful because they reflect outcomes that matter intrinsically to patients, independent of the biological mechanism by which benefit is achieved. However, many clinical endpoints are slow, rare, or ethically difficult to observe. As a result, regulators may approve a drug based on surrogate endpoints.

A surrogate endpoint stands in for a clinical endpoint and is expected to predict clinical benefit, but is not itself the benefit, like albuminuria and progression of chronic kidney disease. In theory, a good surrogate reliably predicts improvement in the clinical outcome of interest. A bad surrogate, by contrast, may move in response to treatment without translating into real benefit, creating the illusion of progress.

In 1989, Ross Prentice introduced the first influential statistical definition of a valid surrogate, arguing that the treatment effect on the clinical outcome must be fully mediated through the surrogate. Although foundational, these “Prentice criteria” proved too rigid, since complete mediation is rarely realistic.

Later work broadened this view.2 In practice, the meta-analytic framework has emerged as the primary approach for validating surrogate endpoints. This approach asks a more practical question: across multiple randomized trials, do treatment-induced changes in the surrogate reliably predict treatment-induced changes in the true clinical outcome?

Regulators have always implemented a more flexible framework. During his time at the FDA in the ‘80s, Dr. Robert Temple distinguished between “validated” surrogates suitable for full approval and “reasonably likely” surrogates that could support provisional use.

A fully validated endpoint is one that regulators already accept as a direct and reliable measure of clinical benefit and, in theory, requires the aforementioned validation of correlation with clinical outcome in interventional trials. An example of a fully validated endpoint is blood pressure for stroke prevention. A reasonably likely endpoint, by contrast, is not yet fully validated but is supported by strong mechanistic or clinical evidence suggesting it predicts benefit. Reasonably likely endpoints are often used under accelerated approval pathways and require confirmatory trials.3 This framework became the foundation of the 1992 Accelerated Approval pathway, created at the height of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

How does the FDA decide which surrogates are valid?

Historically, the FDA has had considerable discretion in deciding which surrogates can support approval and did not follow a single, standardized framework for deciding whether a surrogate endpoint could be used to approve a drug. Instead, decisions were made one drug at a time, based on internal scientific judgment, informal precedent, and private discussions between FDA reviewers and individual sponsors. Review teams weighed a mix of considerations, including whether the surrogate made biological sense for the disease, whether prior studies showed an association between the surrogate and real clinical outcomes, and whether similar endpoints had been accepted in related contexts.

Importantly, the FDA rarely required a uniform level of statistical validation, and acceptance of a surrogate for one drug did not automatically establish it as acceptable for future drugs targeting the same indication. As a result, the process was opaque and ad hoc, with outcomes that could be influenced by case-specific negotiations rather than clear, reusable standards.

The 21st Century Cures Act of 2016 sought to address this by mandating the FDA to establish a transparent Biomarker and Surrogate Qualification Program (BQP). BQP allows a biomarker to be qualified for a specific context of use across drug programs, with surrogate endpoints facing the highest evidentiary bar. For a surrogate, the FDA requires meta-analytic evidence across multiple randomized trials showing that treatment effects on the biomarker reliably predict treatment effects on the true clinical outcome at the trial level. This cross-trial meta-analytic requirement is meant to demonstrate causality and generalizability beyond any single drug or study.

Congress hoped to transform private negotiations into a standardized, public pathway where qualified surrogates could be reused by any sponsor. Yet the promises of BQP have not been realized. The Study to Advance Bone Mineral Density as an Endpoint (SABRE), the most advanced qualification effort under this program, achieved qualification of bone mineral density (BMD) as a surrogate endpoint for osteoporosis trials on December 19, 2025. Initiated in 2013, SABRE took more than a decade, despite the fact that BMD is a widely measured biomarker in osteoporosis interventional trials, meaning no new data generation has been required. Even more concerning, only four additional surrogate endpoints are currently progressing through the BQP pipeline, underscoring the program’s lengthy timelines and limited throughput.

At the same time, the 21st Century Cures Act required the FDA to publish, for the first time, an official list of surrogate endpoints it considers acceptable for approval, largely reflecting historical precedent. These endpoints continue to support approvals under the older, ad hoc system and can be understood as “legacy surrogates”: measures that persist by precedent rather than through transparent, up-to-date validation.

A 2024 systematic review found that 22 of 37 surrogate markers used in non-oncologic chronic-disease trials lacked any published meta-analysis linking treatment effects on the surrogate to patient outcomes. Of the 15 with at least one meta-analysis, only 3 showed consistently strong associations.

Together, these dynamics create a “worst of both worlds” equilibrium. The system is most demanding where new, potentially better endpoints are trying to enter, and least demanding where old, potentially weak endpoints are already entrenched. In practice, this means rigor is applied in the wrong place: legacy surrogates are rarely audited, while novel surrogates face an obstacle course.

The pipeline from biomarker to surrogate endpoint

BMD for osteoporosis is an unusually favorable case. BMD was first measured quantitatively in the late 1960s and entered clinical research use for osteoporosis in the 1970s, becoming an established diagnostic biomarker for osteoporosis. Because of this, decades of clinical trials had measured it routinely and generated most of the evidence needed for surrogate endpoint qualification, without requiring new interventional studies. This means that the data for qualification already existed by the time the SABRE effort started.

In basic research, novel biomarkers of disease are constantly being discovered through various genomic, proteomic or physiological studies that identify biological features associated with disease processes or progression. By contrast, developing new surrogate endpoints from these emerging biomarkers or other biological measures is far more difficult, because qualification-grade evidence—specifically, data demonstrating that intervention-induced changes in the measure reliably predict meaningful clinical outcomes across multiple trials—does not yet exist.

In theory, the most promising biomarkers should advance along a sequence from laboratory to clinical use:

- from discovery

- to analytical validation

- to clinical validation

- to demonstrating that modifying the biomarker alters clinical outcomes

- and finally to formal qualification as a surrogate endpoint that can replace hard clinical endpoints in trials (via BQP).

Although biomarker discovery research is heavily funded and thriving, the progression outlined above almost never occurs. While not all biomarkers are suitable candidates for surrogate endpoints, the gap between the scale of basic biomarker discovery and the scarcity of biomarkers that undergo rigorous, regulator-ready validation is striking.

ARPA-H’s PROSPR program is designed to intentionally generate the evidence needed to qualify novel biological measures,4 like intrinsic capacity (IC), as surrogate endpoints for clinical trials of aging interventions. But programs like PROSPR remain extremely rare5 and illustrate how long the process of going from novel biomarker to surrogate endpoint is. Notably, IC was first formally introduced by the World Health Organization in 2015. Considering that SABRE took over a decade to qualify BMD despite extensive pre-existing interventional data, the implied timeline to qualify a truly novel biomarker — one without a large body of randomized trial evidence — could easily stretch to decades. Absent institutional reform, qualifying a new biomarker as a new endpoint is not a near-term or even medium-term strategy, but a multi-decade bet.

A set of practical barriers makes endpoint validation and qualification unusually difficult: interventional data are fragmented across sponsors and studies, and researchers can spend years simply assembling the evidence needed to meet regulatory standards, while the qualification process itself remains opaque and unpredictable. These challenges are reinforced by misaligned incentives, as academic reward structures favor novelty over validation and discourage researchers from designing biomarkers with downstream clinical or regulatory utility in mind, leaving many candidates ill-suited for eventual qualification from the outset.

Although industry could in principle fund surrogate validation where academic investment falls short, the need for large upfront investment, combined with long timelines, regulatory uncertainty, and the fact that qualified surrogates function as public goods available to all sponsors, substantially weakens private-sector incentives to do so.

Conclusion

Surrogate endpoints are among the most powerful instruments for accelerating clinical trials and, by extension, biomedical progress. Yet they currently sit in a deeply inefficient equilibrium. On one side is an entrenched reliance on a set of weak, expedient, and often outdated surrogates that persist largely due to historical precedent. On the other is a chronic underinvestment in the discovery, rigorous validation, and maintenance of stronger alternatives.

Overall, surrogate endpoints are a perfect example of a high-leverage technology whose development is bottlenecked by institutional, regulatory, and legal constraints. Not having good surrogates is a policy choice.

This series will examine those forces in detail and will propose concrete reforms to realign them. We begin by analyzing how the FDA’s Biomarker Qualification Program (BQP) operates in practice. Through a case study on the SABRE effort, we show how even biomarkers supported by extensive data can remain stalled for years in regulatory limbo. This illustrates how procedural friction, misaligned incentives, and lack of transparency suppress progress. More broadly, the series will interrogate the incentive structure governing biomarker research itself. Discovery studies reliably attract funding, while the work of establishing clinical relevance remains structurally under-resourced. As a result, the system systematically overproduces candidate biomarkers and underproduces usable endpoints. We will also investigate the problem of weak endpoints, mostly legacy surrogates that persist without rigorous audit.

Realigning these incentives would have effects far beyond marginal improvements in trial design. High-quality surrogate endpoints shorten time-to-readout, reduce trial costs, and make entire therapeutic areas tractable. Surrogate endpoints should be treated as shared assets, not one-off approval tools, and they require sustained, collective investment to work. The potential gains are substantial, and deciding not to pursue them means deciding to leave patient benefits unrealized.

We thank Dr. Manjari Narayan for offering her time and expertise in discussing general concepts around surrogate endpoints.

-

A clinical endpoint is an outcome in a clinical trial that directly measures how a patient feels, functions, or survives, reflecting real clinical benefit rather than a biological proxy. Examples include overall survival, symptom improvement, functional ability, and quality-of-life measures.

-

Regression-based measures, such as the proportion of treatment effect explained, treat surrogacy as a spectrum rather than all-or-none. Causal inference reframes surrogate evaluation in terms of the direct and indirect (mediated) causal effects of treatment. However, most of these methodologies remain academic.

-

Critics have pointed out that there is insufficient follow up via post-approval studies.

-

The term “novel” here is relative and mostly refers to the fact that intrinsic capacity is a composite endpoint that has been developed de novo. In practice, IC was first proposed to be associated with morbidity more than four decades ago. IC is a composite endpoint that quantifies overall physical and mental function by integrating measures of locomotion, cognition, psychological health, vitality, and sensory capacity into a single, continuous parameter.

-

As far as we are aware, this is the only program of its kind funded by the government.